Did the Fellows gathered at the Royal Society in February 1738 really entertain an account of a mermaid? Well, not quite, as Rupert Baker discovers.

I’m constantly impressed by the number of records my colleagues add on a weekly basis to our online archive catalogue: we’re up to nearly 300,000 records now, and work continues apace. Until everything is documented down to item level, however, I’m still in the habit of checking our old-school card catalogue to fill in the gaps when I’m answering enquiries.

This can be useful, but it also has its distractions. While looking for correspondence on auroras from a ‘Mr J Bradley’ recently, I flicked my way to this index card recording a paper from ‘BRADLEY, A’, read at the Royal Society in February 1738, and was immediately stopped in my tracks. A mermaid! Time to investigate – well, could you resist?

That reference is from our Register Book Copy (RBC), which suggested that there would be an original document in our Classified Papers series. Once I’d realised that (unusually) there’s a minor typo on the index card, which should read ‘squatina’ rather than ‘squalina’, I found my way to the manuscript in Classified Papers volume 15, ‘Zoology’.

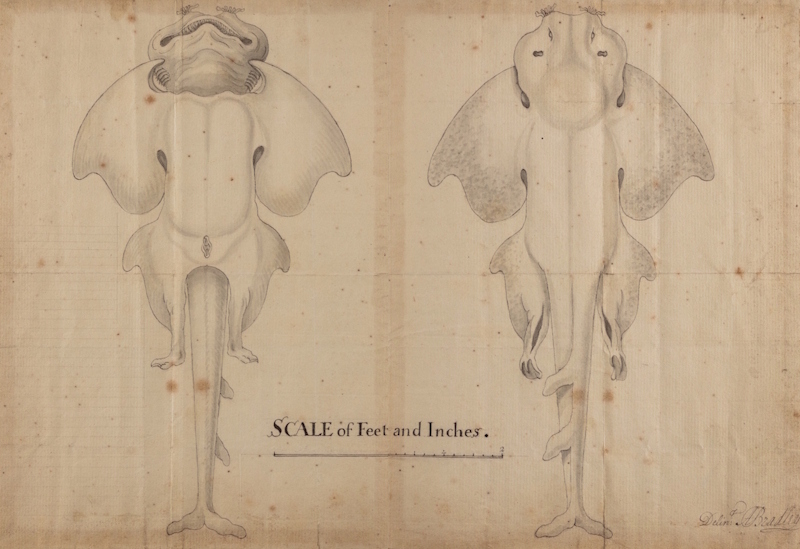

The paper in question is now digitised on our Science in the Making platform, and features an actual picture of the ‘mermaid’. The original is rather tightly bound, though, with the creature’s head on the gutter side and hence tricky to photograph. There’s a clearer version copied into the Register Book Original ‘Account of the Aquila Squatina Salviana’ (RBO/21/15), allowing you to get a look at the mysterious creature for yourself:

So, what did Mr Bradley observe – and did the natural philosophers gathered at the Royal Society in February 1738 really entertain an account of a mermaid? Well, to the credit of eighteenth-century gentlemen of science, but the slight disappointment of your cryptozoology-chasing librarian, it appears that Bradley knew he was looking at a fish all along: the first line reads, ‘This fish was taken off Exmouth Bar on Septr. the 9th 1737 by Robert Heath Fisherman with the assistance of his partner.’

Heath may have wondered exactly what he had on the end of his line, however – he described to Bradley how, ‘after he had taken a Hitch about its Tail, whenever he veer’d the Line to give it Liberty, it stood erect upon the two seeming Legs, bore its Head forward, & spouted a quantity of Water very high…’. There are quite a few other references in Bradley’s paper to body parts which sound curiously human: ‘upon the upper part of each Foot it had an apparent Toe in the same place of the great Toe in [the] human Body: and had regular joints at its Ankles, Knees and Hip parts, if I may term them so.’

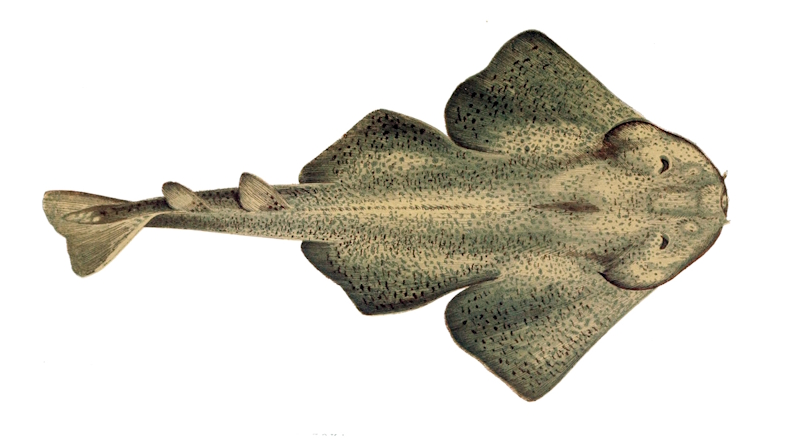

It seems that the creature Heath and his fishing partner landed, salted and sent to Exeter for further examination was in fact an angel shark, Squatina squatina: this 1877 illustration from a work by Henri Gervais and Raoul Boulart certainly bears a strong resemblance to the picture in our Register Book:

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Intrigued as to the presence of any similarly fishy tales, I cast my net wider (as it were) and came across another entry in the Classified Papers, this time in volume 13, ‘Monsters and Longevity’. The mystery here lies in how this paper, ‘A mer-man’, came to be in our collections in the first place, as it’s an extract copied from a sixteenth-century book, the Chronicles of Raphael Holinshed, and doesn’t appear to be linked to any particular Fellow, or to have been read at a Royal Society meeting or published in the Philosophical Transactions.

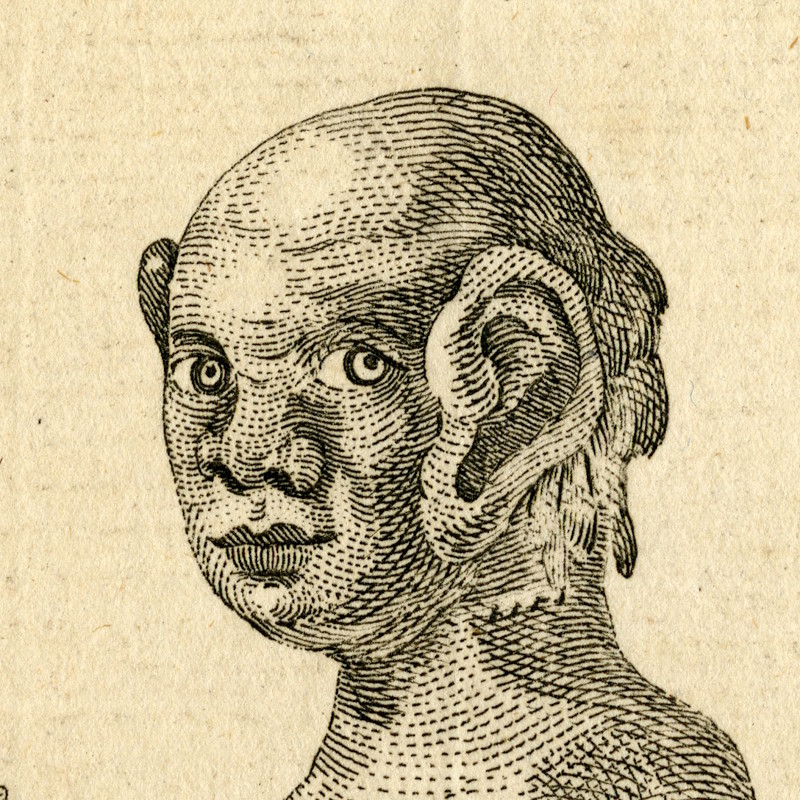

The incident it relates is said to have taken place at Orford in Suffolk during ‘King John’s reign’ (1199-1216). Maybe the Fellows just passed the manuscript around as a curious historical anecdote before filing it at the Society; with its descriptions of a balding merman with a beard and hairy chest, who did not speak, ate fish raw and eventually escaped back into the sea, never to be seen again, it’s certainly a lively read. Holinshed (c.1525-1582) was writing in a more credulous age, of course – a time of sea serpents and ‘sea monsters in monks’ habits’, as depicted in this wonderful illustration I found in our 1558 copy of the Histoire entiere des poissons by Guillaume Rondelet:

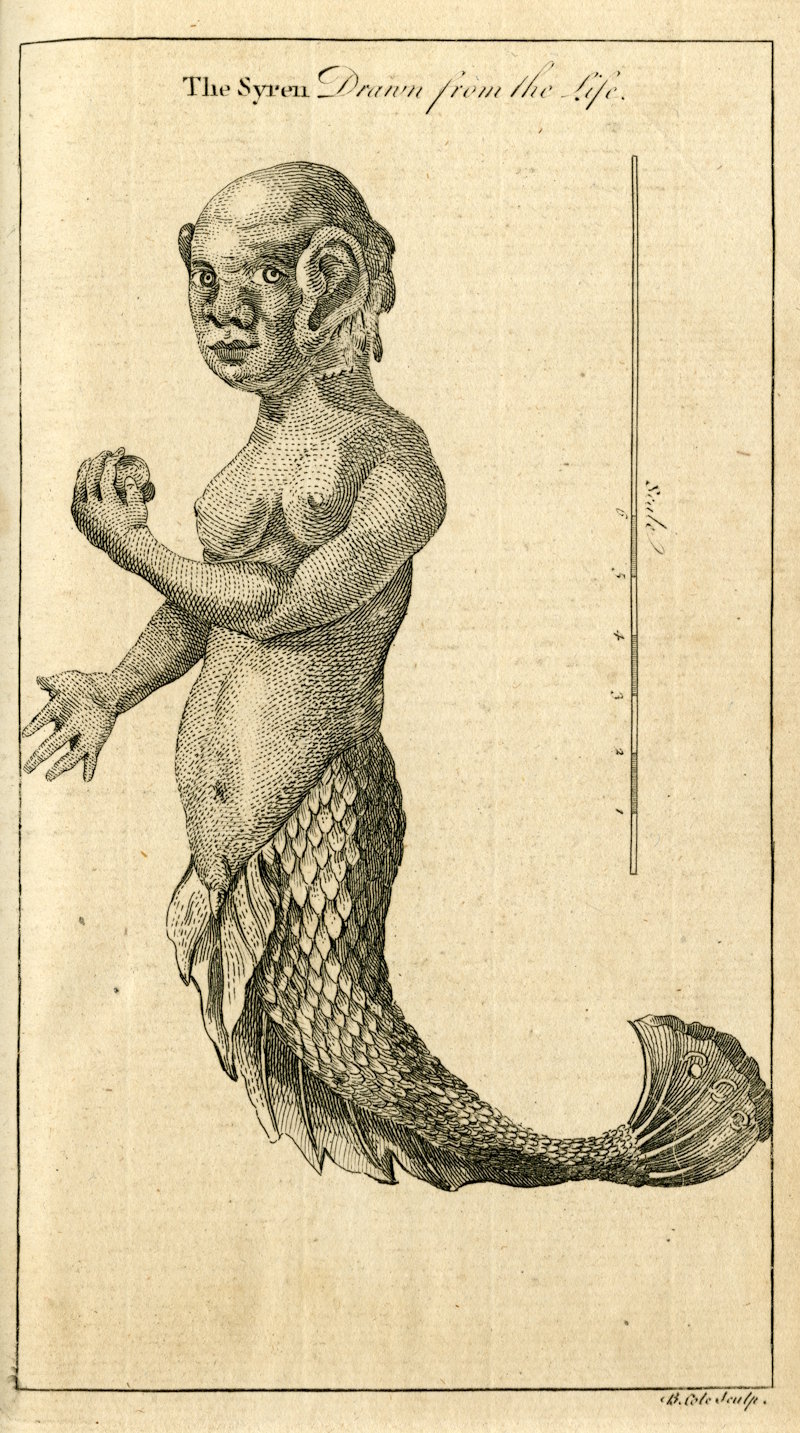

There’s definitely one mermaid engraving from an eighteenth-century periodical in our printed collections, and also digitised on our Picture Library (RS.21244):

It’s from The Gentleman’s Magazine, a digest of news and gossip which (as I’ve pointed out in an earlier blogpost) was never shy of veering towards the quirky. Their ‘Syren, or Mermaid’ is reported as being ‘about two feet long, alive, and very active, sporting around in the vessel of water in which it was kept with great seeming delight and avidity […] the skin was harsh, the ears very large, and the back-parts and tail were covered with scales.’ The fresh water in the vessel was matched more closely to the mermaid’s usual marine environment by adding a large pinch of salt, presumably…

You’re welcome to experience the slippery slopes of our catalogue card index by coming into the Library and flicking through the drawers for yourself. If you’re unable to visit in person, our friends on the Objectivity YouTube channel have just put together a highlights reel of their ‘White Gloves of Destiny’ series, where celebrity guests select a topic via a random card picked from the drawers; there’s also a playlist of all the White Gloves videos. No mermaids, but there are water bellows, barnacles and turtles – enjoy!