Jon Bushell pays a visit to the Roman ruins at Silchester, which have captured the attention of several Fellows of the Royal Society.

While out enjoying the good weather on a recent hike, I visited the fascinating ruins at Silchester. Originally an Iron Age settlement, the site became the town of Calleva Atrebatum following the Roman conquest of Britain.

Situated on an important route from London to Bath, the place prospered until the Romans left Britain in the early fifth century. It remained occupied for a time, but gradually fell into decline and was abandoned. While the town’s buildings have long since vanished, the walls and amphitheatre remain in remarkably good condition. Their existence was no secret, but scholarly interest in them only really began in the sixteenth century when antiquary John Leland wrote a description of the site around 1540, during his tour of Britain.

Silchester also captured the attention of several Fellows of the Royal Society. At the time of the Society’s foundation in 1660 there was no equivalent antiquarian organisation, and many among the Fellowship combined antiquarian interests with their natural philosophical pursuits. The Society was certainly happy to encourage them: when Walter Charleton submitted his plan of Avebury in 1663, Council instructed James Long and John Aubrey to make further investigations. Aubrey himself visited Silchester in 1667 to examine the ruins.

The southern entrance to the ruined amphitheatre at Silchester

The southern entrance to the ruined amphitheatre at Silchester

The Society of Antiquaries was established in the early eighteenth century. Humfrey Wanley, who had worked for the Royal Society as an assistant secretary and was elected to the Fellowship, organised the earliest informal meetings of the Antiquaries in 1707. For much of the eighteenth century there remained a significant overlap in membership of the two societies.

From 1717 the Antiquaries met in the evenings following the weekly Royal Society meetings, at the Mitre Tavern in Fleet Street, chosen because of its proximity to the Society’s home in Crane Court. Their first Secretary was Royal Society Fellow William Stukeley, who surveyed the ruins at Silchester for his Itinerarium curiosum, (1724).

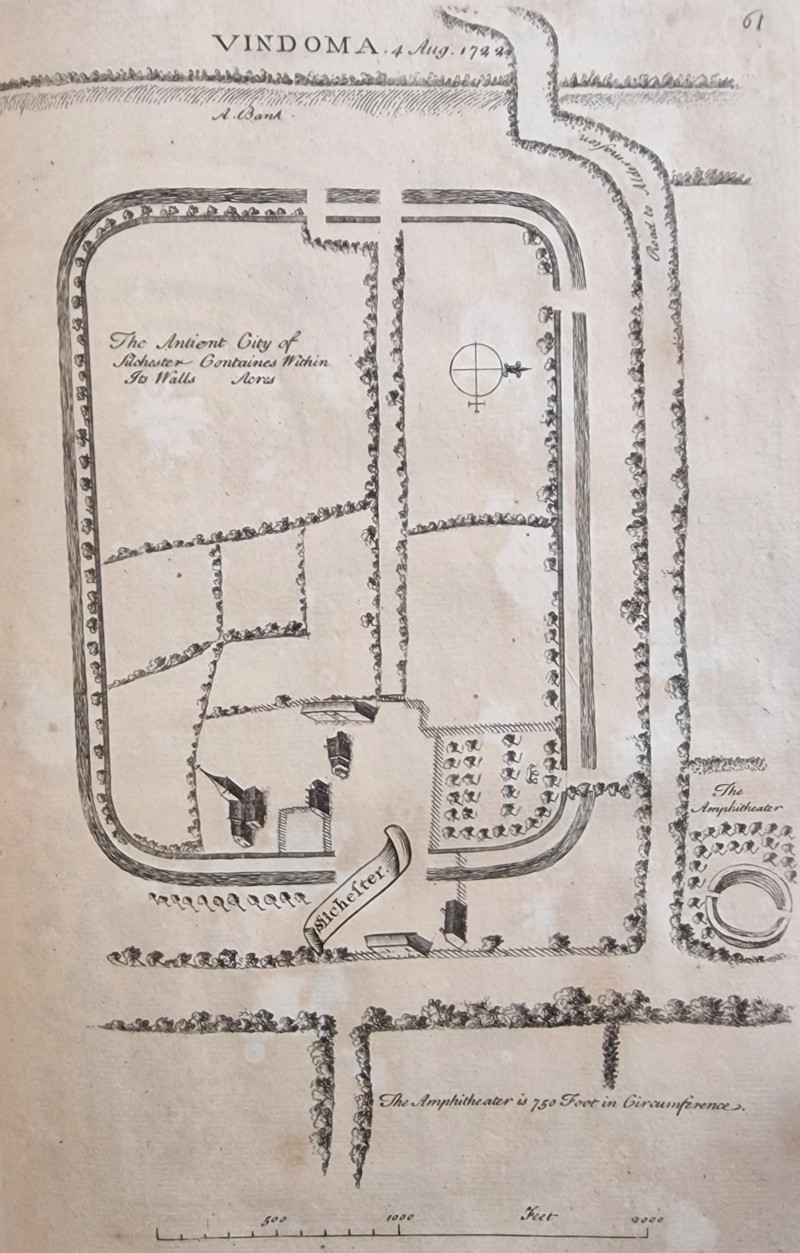

Stukeley’s plan of Silchester, dated 4 August 1722

Stukeley’s plan of Silchester, dated 4 August 1722

One thing that stands out about Stukeley’s plan (above), aside from its general inaccuracy, is the name. Stukeley, like most of his contemporaries, believed that the ruins at Silchester were those of another Roman town, Vindomis. A couple of Royal Society Fellows, Edmond Halley and the antiquary John Horsley, did correctly identify Silchester as the site of Calleva Atrebatum, the latter in his Britannia Romana (1732); Vindomis, however, was the more widely accepted suggestion at the time, even without conclusive proof.

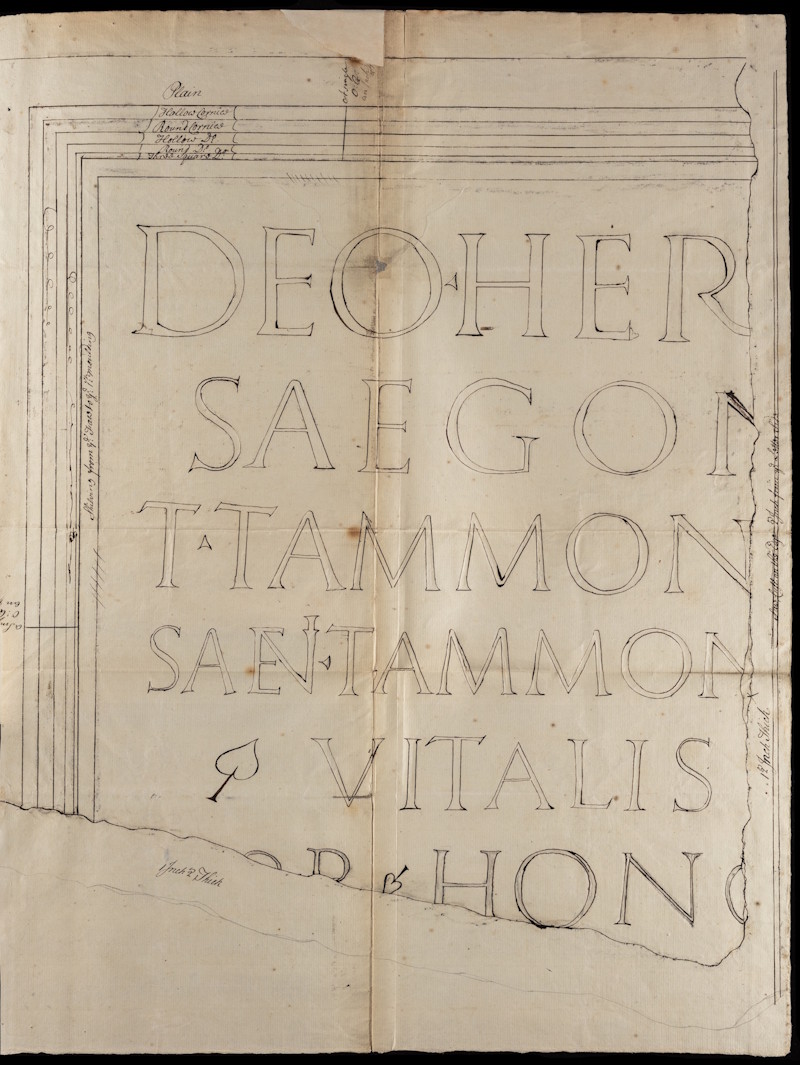

John Ward, Gresham Professor of Rhetoric and another Royal Society Fellow, believed he had finally resolved this question in 1744. A certain John Stair of Aldermaston had spent some time excavating at Silchester, and among his finds was a partial inscription from a forum building. A tracing of this was sent to Ward, who provided a possible translation in a letter to the Society, along with the tracing itself. The indentations on the paper where it was pressed against the original carving are still visible. Ward’s letter was published in the Philosophical Transactions, with a scale image of the inscription.

The tracing of John Stair’s Silchester inscription (L&P/1/332). The original carved stone was lost sometime in the eighteenth century.

The tracing of John Stair’s Silchester inscription (L&P/1/332). The original carved stone was lost sometime in the eighteenth century.

Ward interpreted the first line as a dedication to Hercules, and the second as a reference to the Segontiaci, a tribe mentioned by Julius Caesar which William Camden had (incorrectly) associated with Silchester and Vindomis in his 1586 book Britannia. Modern interpretations suggest the second line is an epithet relating to Hercules and has nothing to do with the Segontiaci. However, Ward saw this as conclusive proof that Silchester was the site of Vindomis and his conclusion was generally accepted at the time.

Even so, the debate over Silchester’s identification rumbled on and wasn’t fully resolved until 1907. During an excavation led by the Society of Antiquaries, another stone inscription was found (now in Reading Museum) which mentioned Calleva, proving Halley and Horsley had been right all along.

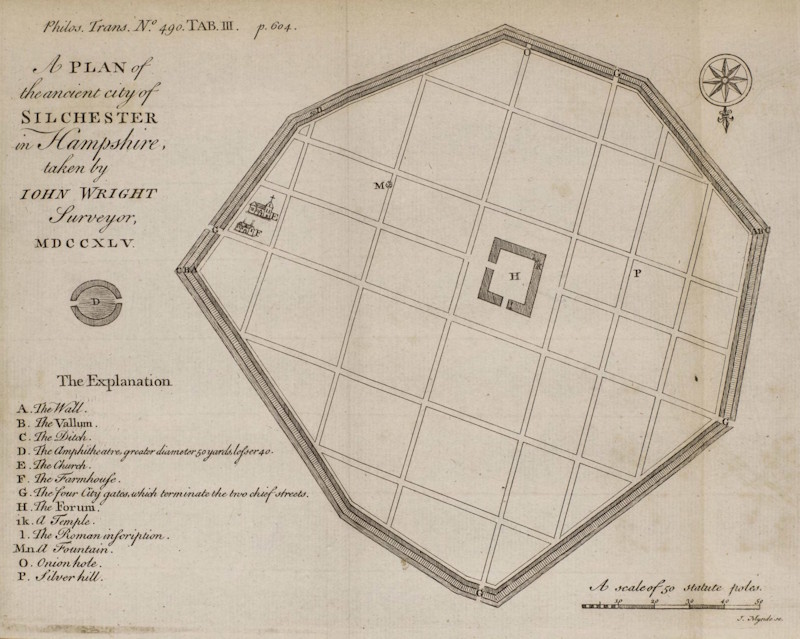

Stair’s tablet clearly piqued Ward’s interest in Silchester, because in 1745 he visited the ruins in person. Stair and a local surveyor, John Wright, had begun working on an accurate plan, which included the town walls and also several main streets and buildings which were visible as lines in the crops planted at the site. While Ward was at Silchester they also measured the dimensions of the amphitheatre. Once the plan was complete, a copy was sent to Ward, who presented it to the Royal Society for publication in the Philosophical Transactions in 1748.

John Wright’s 1745 plan of Silchester as it appears in Ward’s 1748 paper

John Wright’s 1745 plan of Silchester as it appears in Ward’s 1748 paper

This plan was much more accurate than Stukeley’s attempt, with the walls and many of the streets located correctly when compared to a modern survey. Stair and Wright correctly located the forum building and identified a number of ruined structures within the town. Interestingly, we don’t have John Wright’s original plan, which the Philosophical Transactions plate is certainly based on, in the Society’s archives. This was held at the British Museum in the nineteenth century and is now in the British Library.

By the end of the eighteenth century the interests of the Royal Society had largely moved away from antiquarian matters. The growth of the Society of Antiquaries had a large part to play in this, as they received a Royal Charter in 1751 and were publishing their own journal, Archaeologia, from 1770. The two Societies remained close, sharing rooms in Somerset House from 1780 and both moving to Burlington House in the 1850s.

Further investigation of Silchester was therefore left in the capable hands of the Society of Antiquaries, who ran a successful excavation programme between 1890 and 1909 which resolved the aforementioned identification debate and developed much of our current understanding of the site. Twenty years is a long time to spend digging, but Rome, as they say, wasn’t built in a day.