Early Fellows of the Royal Society had many questions about the geology, topography and meteorology of Iceland, as Ainsley Vinall discovers.

While looking through the ‘Questions and Answers’ volume of our Classified Papers collection recently, I noticed that several of the lists of questions were written about Iceland. In fact, the very first document bound into the volume is a set of enquiries about its unique geology and topography. Intrigued, I decided to investigate why early Fellows of the Royal Society were so interested in this singular island on the edge of the Arctic Circle.

This first list of questions was drawn up in December 1662 by John Hoskyns FRS (1634-1705), who wanted to know what ‘sort of mineralls besides brimstone are digged up neere Hecla’ (Hekla), one of Iceland’s most prominent volcanoes. He also asked about ‘holes wch if a stone bee throwne into them throw it back againe’ and a ‘deep pit into wch if a stone bee thrown it is a long while falling but after sometime water boyles out at top’ – possibly distorted references to Iceland’s geysers, which spout boiling water into the air and were sometimes stuffed with stones or turf to trigger an eruption.

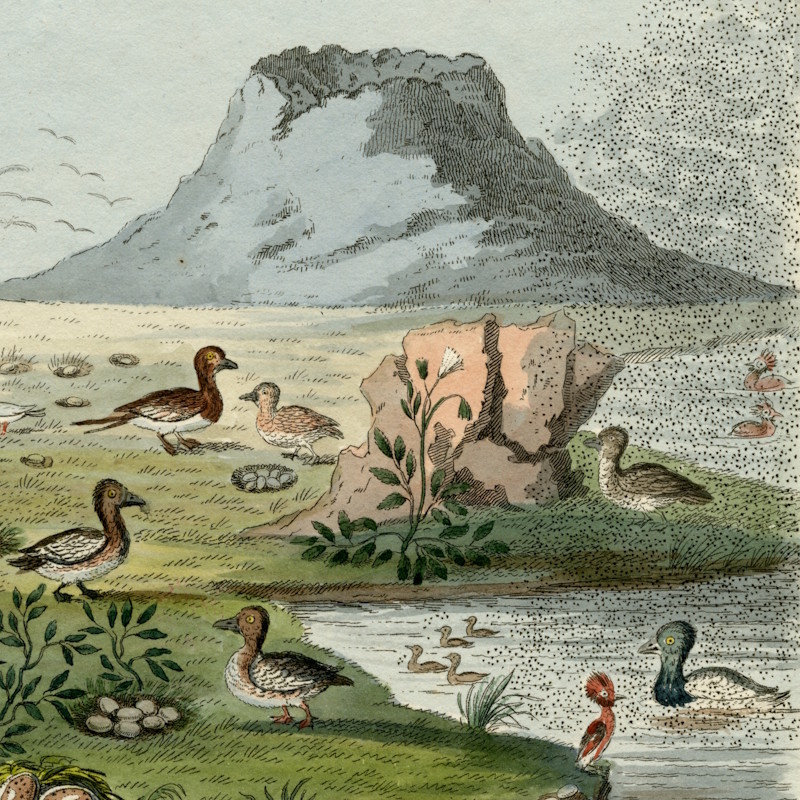

Hoskyns also had some stranger queries: he was keen to hear about a lake that ‘kills ye birds yt fly over it’, and another that is ‘always smoaking though cold into wch if wood bee thrown it turnes it to stone’. These are a little harder to decipher. The smoking lake could refer to the Gunnuhver geothermal area that is dotted with steam vents and thermal pools, as it is described as being ‘on the west side of the isle’. The fatal lake is harder to interpret, as Iceland’s lakes are generally considered to be excellent habitats for waterbirds, with the volcanic lake Mývatn supporting many species of ducks, swans and grebes… and midges, as shown on the right hand side of this picture:

Waterfowl of Mývatn, from Reise im Norden Europa's vorzuglich in Island by F A L Thienemann and G B Gunther (1824) RS.12523

Waterfowl of Mývatn, from Reise im Norden Europa's vorzuglich in Island by F A L Thienemann and G B Gunther (1824) RS.12523

A month later, in January 1663, Robert Hooke FRS (1635-1703) wrote a second list with a further 26 questions about the island. Reflecting Hooke’s role as the Society’s curator of experiments, this has a much more scientific character, asking for answers derived from accurate tests. Hooke wanted to know ‘how much colder the winter is there than here, by a sealed thermometer’; he also enquired as to ‘how deep the frost pierceth the earth below the surface’ and ‘whether iron be more or less apt to rust there than here’.

His list puts an emphasis on comparing Iceland to England and quantifying these differences. One question even suggests an experiment involving ‘a bladder full blown with English air to be carried thither, and another full of that air brought back’, to determine if there is a difference in pressure or composition.

Although I’ve not found any evidence that Hooke’s experimental air exchange took place, in 1675 the Royal Society did arrange for some materials to be sent to Iceland so that other experiments could be conducted. After the Society’s secretary Henry Oldenburg FRS (c.1618-1677) received some answers back from Rasmus Bartholin (1625-1698), a Danish physician familiar with Iceland, he was put in touch with Gísli Þorláksson (1631-1684), an Icelandic bishop.

Þorláksson had penned the responses to questions about whether certain materials became frozen or corroded when exposed to Icelandic air, but he lacked the necessary ‘quicksilver’ and ‘spirits of salts’ to provide all the requested answers. Oldenburg therefore instructed Bartholin to ship the required materials to Þorláksson to enable these experiments to be conducted.

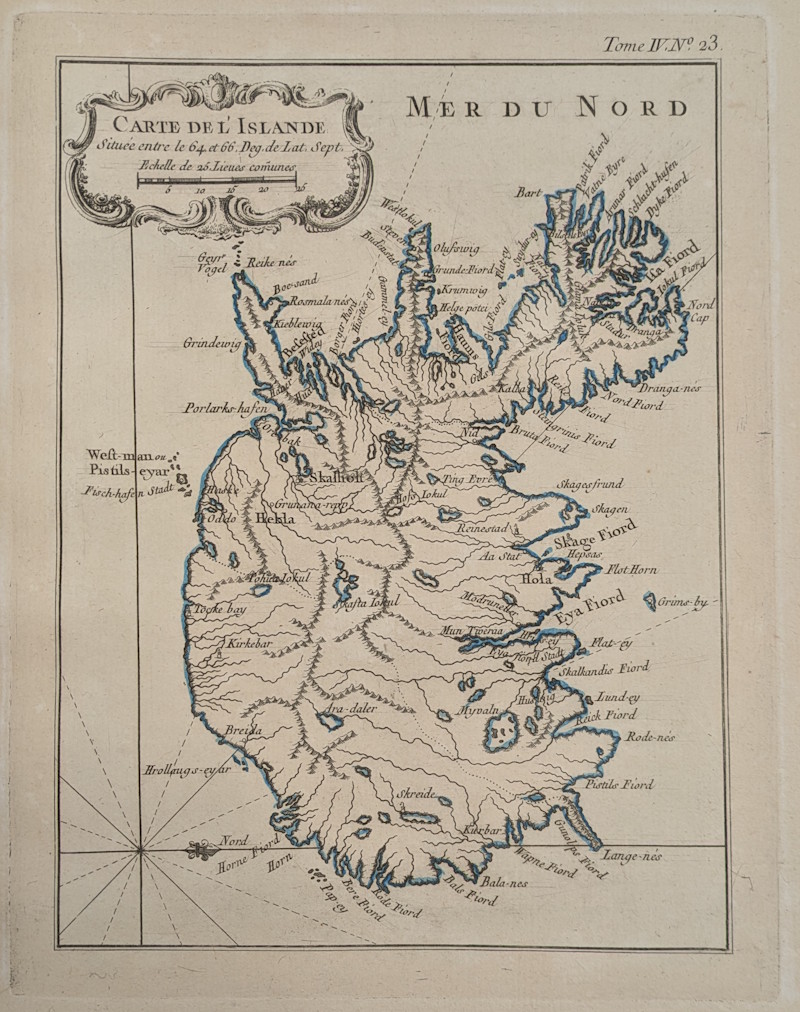

Carte de l’Islande from Le petit atlas maritime by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin (1764)

Carte de l’Islande from Le petit atlas maritime by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin (1764)

As well as making contact with scientifically-minded Icelanders, the Royal Society also began to acquire books on Iceland in the 1670s. Our copy of Dissertatio chorographico-historica de Islandia (1666) by Þórður Þorláksson (1637-1697), Gísli’s brother, includes an inscription that shows this history of Iceland was acquired in April 1671. It’s now bound together with an earlier account of the island, Crymogæa (1609) by Arngrímur Jónsson (1568-1648). Through these books and letters, the Fellows started to form a more accurate picture of the island.

However, it wasn’t until 1772 that a Fellow of the Royal Society finally made the journey to Iceland, when Joseph Banks FRS (1743-1820) sailed there on the Sir Lawrence. Banks took a more hands-on approach to answering his questions about Iceland, spending six weeks collecting specimens, climbing Hekla and measuring the height of the geysers’ eruptions. He later convinced William Jackson Hooker FRS (1785-1865) of the value of a botanical excursion to Iceland and in 1809 Hooker made a visit of his own.

View of the Geyser, engraved after a sketch by Sir John Thomas Stanley (1796) RS.14040

View of the Geyser, engraved after a sketch by Sir John Thomas Stanley (1796) RS.14040

Hooker’s expedition was a little more eventful. At this time, Iceland was ruled by Denmark, allied with France in the Napoleonic Wars. Hooker sailed on a merchant ship, the Margaret and Anne, whose journey had been organised by Danish privateer Jørgen Jørgensen (1780-1841). When they arrived at Reykjavík the local governor insisted that, as the British were an enemy, he would not permit any trade with the ship. Refusing to take no for an answer, Jørgensen incited a revolution, locked up the governor and declared Icelandic independence. The revolution was short-lived as the British navy soon came to collect Jørgensen, who had been captured previously and expressly forbidden from leaving the British Isles whilst out on parole.

Hooker spent nine weeks in Iceland, visiting the historic sites of Þingvellir and Skálholt, observing the geysers and putting together a botanical collection. However, on his return voyage Danish prisoners of war set fire to the Margaret and Anne. Seeing the flames, Jørgensen, who was held as a prisoner himself on another vessel, insisted on being given the helm to navigate a difficult course and rescue the burning ship. Everyone on board was saved, but almost all of Hooker’s specimens and notes were destroyed. When he came to write his Journal of a tour in Iceland (1811) he had to rely on his memory and Banks’s diary from 1772.

Following the release of Hooker’s Tour in Iceland, and similar stories of Icelandic expeditions published in the early nineteenth century, the island became a popular destination for adventurous scientists and travellers alike. If these early accounts inspire you to plan your own voyage, please do bring us back a balloon of Icelandic air.