Two eighteenth-century women, Elizabeth Fulhame and Mary Senex, had contrasting interactions with the Royal Society, as Virginia Mills discovers.

Earlier this year the Royal Society marked the 80th anniversary of the election of its first women Fellows. Their admission was a belated acknowledgement of longstanding female participation in science.

Researching our collections recently, I was struck by the experiences of two women and their contrasting interactions with the Royal Society. Mary Senex, printer and globe seller, used the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions journal as a platform to promote her business, while the chemist Elizabeth Fulhame published her experimental findings independently, despite having an entry point to the Society’s journal.

An essay on combustion (1794) is Elizabeth Fulhame’s only published work. The essay is concerned with her (successful) attempts to chemically infuse cloth with gold and silver, and is now credited as the first description of the principles of catalysis. Her use of photoreduction was also recognised as foundational by pioneers of photography including Sir John Herschel, nearly 50 years later.

As is so often the case with women and other marginalised actors, records of Elizabeth Fulhame are scarce. Almost everything we know about her and her work comes from the pages of the Essay. We’re fortunate that she pursued and published her research in her own name, rather than seeing her contributions subsumed and published under the name of a male relative.

An essay on combustion by Mrs Fulhame (full version online via Hathi Trust)

An essay on combustion by Mrs Fulhame (full version online via Hathi Trust)

What particularly intrigued me was her frank expression of her misgivings, not only about publication and the reception of her work as a female chemist, but specifically regarding presenting her work via the Royal Society:

‘Though I was after some considerable time, able to make small bits of cloth of gold, and silver, yet I did not think them worthy of public attention […] unfavourable judgement suspended my intention of publishing this little work, until a celebrated philosopher happening, some time in October 1793, to see some of the same pieces […] viewed the performance in a very different light. This illustrious friend of science not only approved of the specimens shewn him, but offered to have a memoir on the subject presented to the Royal Society; but different incidents dissuaded me from that mode of publication, and induced me to adopt the present.’

This offers some tantalising threads for the Royal Society history enthusiast to pull on. First, who was the ‘illustrious friend of science’ who encouraged Fulhame? If they were offering to present her work at the Royal Society, they must have been a Fellow to comply with the procedural requirements of the day. Joseph Priestley is a candidate: in his Doctrines of phlogiston (1800) he noted how he had met Fulhame in 1793 and been ‘greatly struck’ by her experiments. Historian Jessica Linker has identified Priestley as promoting Fulhame’s essay through the Chemical Society of Philadelphia, which elected her an honorary member on the strength of this work. Priestley may have acted as an early supporter, but he later drew back when Fulhame’s essay contradicted his own phlogiston theory.

‘Sedition and atheism defeated’: Priestley and other Dissenting ministers dragged to hell by a pack of demons, 1790 (RS.17962)

‘Sedition and atheism defeated’: Priestley and other Dissenting ministers dragged to hell by a pack of demons, 1790 (RS.17962)

As a second loose thread, what might the ‘different incidents’ have been that dissuaded Fulhame from having her work presented to the Society? One at least was probably Priestley’s flight from England to escape persecution for his views as a Dissenter, the summer before her essay was published. Without Priestley to submit her essay to the Society, it may have been necessity rather than choice that forced Fulhame to publish elsewhere. Like all non-Fellows she needed a sponsor to get her paper through the door.

Her prefatory remarks suggest she may have shared Priestley’s tendency for non-conformism at least, if not his politics. Her words paint a picture of her as an innovator and outsider not afraid to disagree with established ideas. She railed against the closed doors of the establishment as ‘dictatorship in science […] fancying their rights and prerogatives invaded […] radically stupid, and malicious, who are the beasts of prey destined to hunt down unprotected genius, to stain the page of biography, or to rot unnoted in the grave of oblivion.’

It's also clear that Fulhame was conscious that her work might be dismissed on the basis of her sex, but far from being cowed by that she called it out in colourful terms:

‘censure is perhaps inevitable; for some are so ignorant that they […] are chilled with horror at the sight of any thing, that bears the semblance of learning […] and if the spectre appear in the shape of woman, the pangs, which they suffer, are truly dismal.’

Fulhame wanted to be acknowledged as an innovator and defend her ideas against plagiarism by bringing them to public attention under her name. Whether she chose to reject the established Royal Society as her platform or found herself without that recourse as an unconnected woman is less certain.

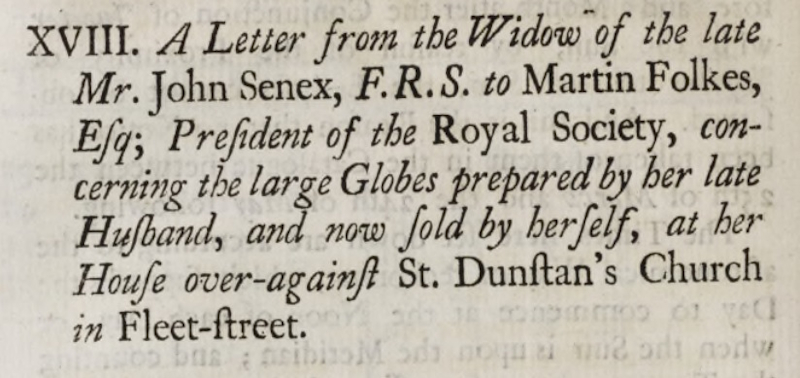

Showing similar conviction in promoting her work, Mary Senex, widow of globe-maker John Senex, did have a letter published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1749. As her husband had been a Fellow she evidently had acquaintances in the Fellowship – up to and including the President, Martin Folkes – she could call on when she took over the business after his death. She used the Society’s meetings and journal as a shop window to advertise the quality of her wares, something at which she seems to have excelled.

Mary Senex’s sales letter, printed in the Philosophical Transactions, 1749

Mary Senex’s sales letter, printed in the Philosophical Transactions, 1749

‘My Globes’, she declared, ‘will be found, upon Examination, as truly made, as accurate, and as well adapted for the Purposes of Geography and Astronomy as any now extant’. Her letter is billed in the Philosophical Transactions as ‘concerning the large Globes prepared by her late Husband, and now sold by herself, at her House […] in Fleet-street.’ Jane Desborough and Gloria Clifton have argued that Mary participated in the globe-making herself, though she would have continued to use her husband’s name in case their quality was called into question – a savvy but disappointing necessity.

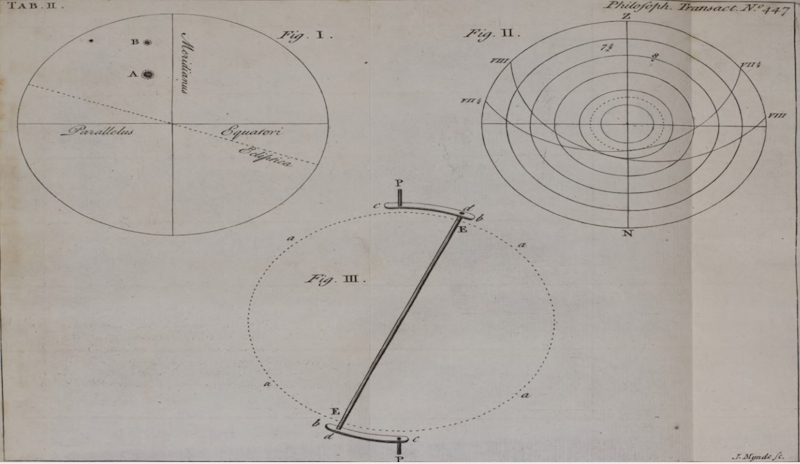

Mary touted the Senex globes as based on the highest quality maps of the Earth and heavens. She also pointed out their cutting-edge technology: adjustable poles so that the celestial globes show the movement of the constellations with the ecliptic accurately year after year. This innovation was the creation of her husband, whose description of the mechanism had previously also been published in the Philosophical Transactions:

Figures from John Senex’s A contrivance to make the poles of the diurnal motion in a celestial globe pass round the poles of the ecliptic, read at a meeting of the Royal Society on 4 May 1738

Figures from John Senex’s A contrivance to make the poles of the diurnal motion in a celestial globe pass round the poles of the ecliptic, read at a meeting of the Royal Society on 4 May 1738

She was seeking the endorsement of her product by the Royal Society in response to reports of superior globes made at Nuremberg, also published in the Philosophical Transactions. In this same publication Mary could claim the superiority of her instruments, and compete for the same customer base in its readership. We know from the records of the Repository catalogue that the Society owned at least two early Senex globes, of 1707. I need to do more digging to find out if Mary’s sales pitch was successful in shifting any more!

Rare surviving pair of Senex globes, terrestrial and celestial, 1740. Recently restored and currently on display at Ham House, National Trust

Rare surviving pair of Senex globes, terrestrial and celestial, 1740. Recently restored and currently on display at Ham House, National Trust

These are just two examples of the many women of science who were orbiting the sphere of the early Royal Society. Their voices come through particularly strongly, but they were unusual in sharing them in such a public manner. The fact that they did gives us a chance to celebrate them, and an insight into the choices and routes available to them to leave their mark.

Top image: detail from ‘Natural philosophy’, by Etienne Fessard after Edmé Bouchardon, 1740 (RS.21340)