Jon Bushell spins a tale of spider research by early Royal Society Fellows, featuring Robert Hooke, John Ray and Martin Lister.

There’s a curious entry in the first volume of the Royal Society’s Journal Book, previously mentioned in this blog, recording how an experiment was carried out at Gresham College to assess the efficacy of powdered unicorn horn as a spider repellent. The ‘unicorn horn’ was possibly a gift from the Duke of Buckingham, who promised to bring one in when he was elected a Fellow in June 1661. But what of the spider – does this indicate a wider interest in spiders among the early Fellowship?

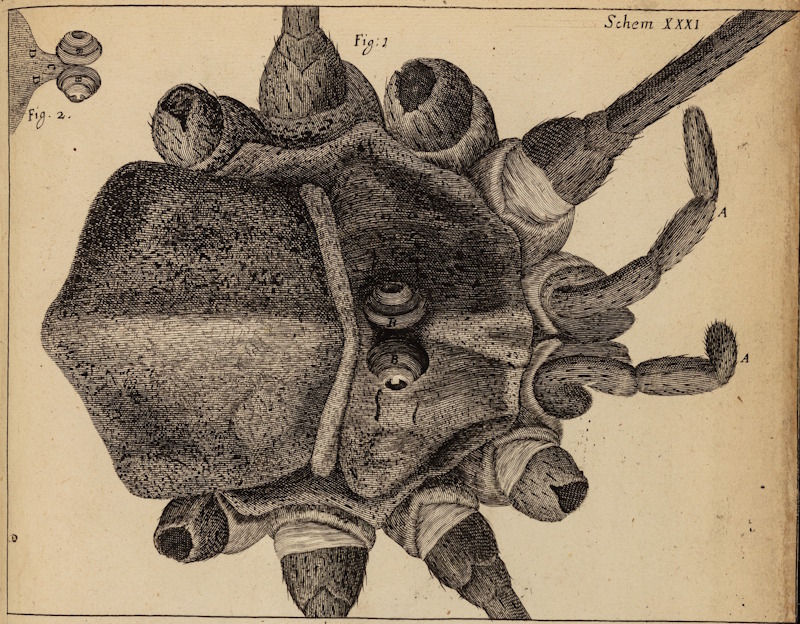

When Robert Hooke was observing ‘minute bodies’ under his microscope for Micrographia, he did take a brief look, and included a description of the ‘Shepherd Spider, or long legg’d spider’. The accompanying plate clearly shows two raised eyes protruding from the head, which Hooke noted as ‘differing from most other Spiders’. He’s absolutely right on that point, as this is clearly a harvestman, which we now recognise as a separate order of arachnids (Opiliones – usually two eyes) from actual spiders (Araneae – generally eight eyes).

Robert Hooke’s drawing of the ‘Shepherd Spider’, from Micrographia (1665)

Robert Hooke’s drawing of the ‘Shepherd Spider’, from Micrographia (1665)

Hooke also described a small grey and black ‘hunting Spider’, likely the common British Zebra spider. Although there is no drawing, Hooke gave a colourful account of their behaviour written by John Evelyn. Given the sheer diversity of spider species, it seems strange that Hooke didn’t devote more of the book to them. The text of Micrographia certainly suggests that he had examined others; however, he stated that it would be an ‘almost endless’ task to describe them all, before swiftly moving on to insects, including his famous flea. Perhaps he simply wasn’t a fan of spiders.

The naturalist John Ray, one of Hooke’s contemporaries, certainly wasn’t, and once confessed his dislike for them in a letter to his friend (and arachnophile) Martin Lister. In 1668, Lister shared a list of 30 spider species he had identified in England, and also sent Ray the first written account of the creatures using their thread to become airborne, a process known as ballooning. Lister’s report was forwarded to the Royal Society by Ray and printed in the Philosophical Transactions.

Because the account was published anonymously, the discovery was credited to Ray himself in some European circles. It also led to a disagreement over priority when the account of another observer of ballooning spiders, Edward Hulse, was forwarded to the Society by Ray and published a year after Lister's. While Hulse’s paper was followed by a note confirming that Lister had written the earlier anonymous piece, and Ray certainly never intended to obscure Lister’s authorship, this controversy seems to have strained their friendship.

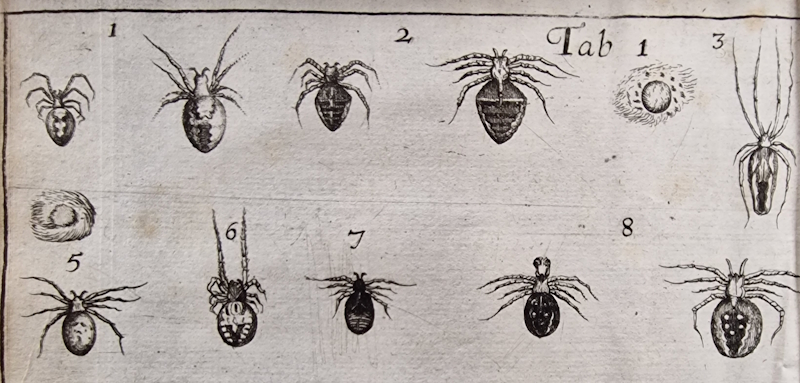

Lister wrote directly to Oldenburg in 1671 to provide him with a copy of his catalogue of English spiders, which had now grown to ‘at least 33’ species. His medical career absorbed much of Lister’s time, but he continued to pursue natural history interests. In 1678 the Royal Society published his Historiae animalium Angliae, bringing together work on snails and shells with descriptions of spiders (we also have an excellent modern translation of the section on spiders, by the way). He included 38 species in the volume, and was convinced that his list was comprehensive, stating that it would be difficult to find one he had missed.

Detail of a plate from Lister’s Historiae animalium Angliae (1678)

Detail of a plate from Lister’s Historiae animalium Angliae (1678)

Francis Willughby saw a version of Lister’s table around 1670, expressing doubts about its completeness. Willughby believed he could identify at least twice that number, but his untimely death in 1672 meant this was never pursued. Ray had access to Willughby’s notes while putting together his Historia insectorum, but Ray’s death in 1705 left that unfinished too. When it was posthumously published in 1710, the section on spiders simply reused Lister’s text from Historiae animalium Angliae, with a few additional remarks by Willughby. Since Historia insectorum was printed without the plates that accompanied Lister’s book, there was little to recommend it to the avid arachnologist.

Lister didn’t provide any formal names for the spiders he described, but his classification scheme is interesting. He separated the 38 species into either two-eyed or eight-eyed varieties, effectively distinguishing Opiliones from Araneae. He then subdivided the eight-eyed species into either web builders or hunters, with the web builders divided further based on the form of webs they spun.

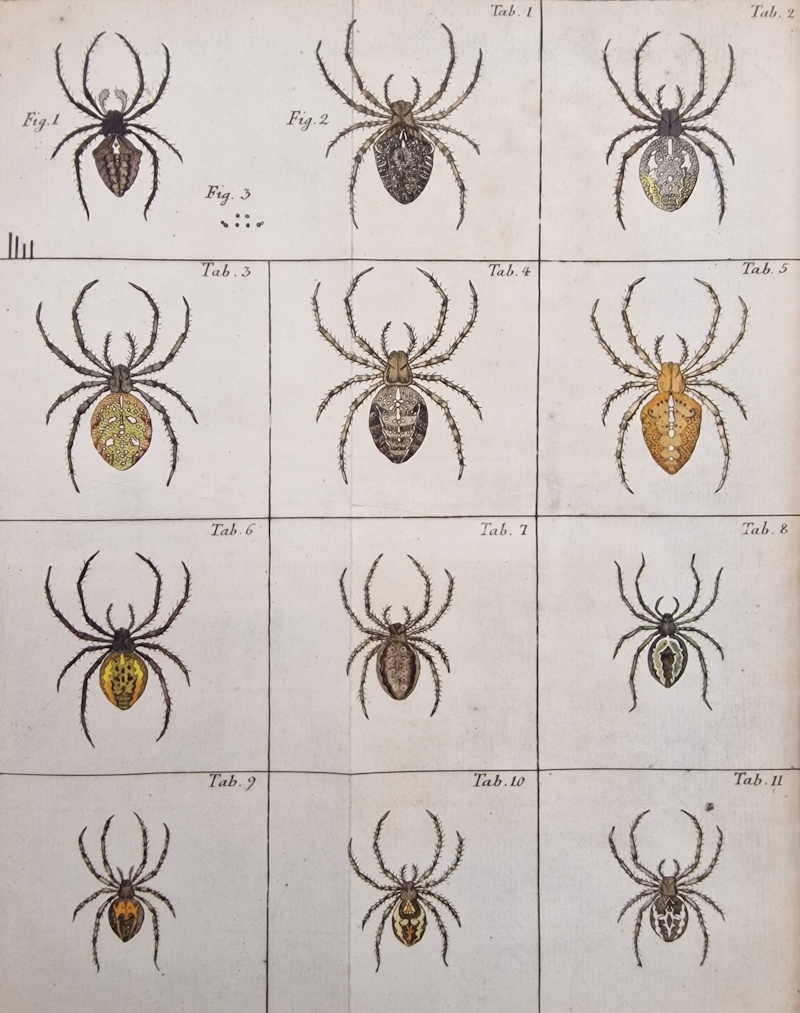

Plate 1 from Carl Alexander Clerck’s Svenska spindlar (1757)

Plate 1 from Carl Alexander Clerck’s Svenska spindlar (1757)

Lister’s classification proved popular, remaining an authoritative text for nearly a century. The tenth and most important edition of the Systema naturae of Carl Linnaeus was published in 1758, introducing binomial nomenclature to the field of zoology. Linnaeus referenced Lister’s work directly and named fifteen of the species he had documented. Interestingly, however, Linnaeus was not the first to publish the authoritative nomenclature for spiders. Carl Alexander Clerck used the same naming system in his 1757 book of Swedish spiders, Svenska spindlar. Not only did he beat Linnaeus to print, he also identified 67 species, more than double the number Linnaeus described.

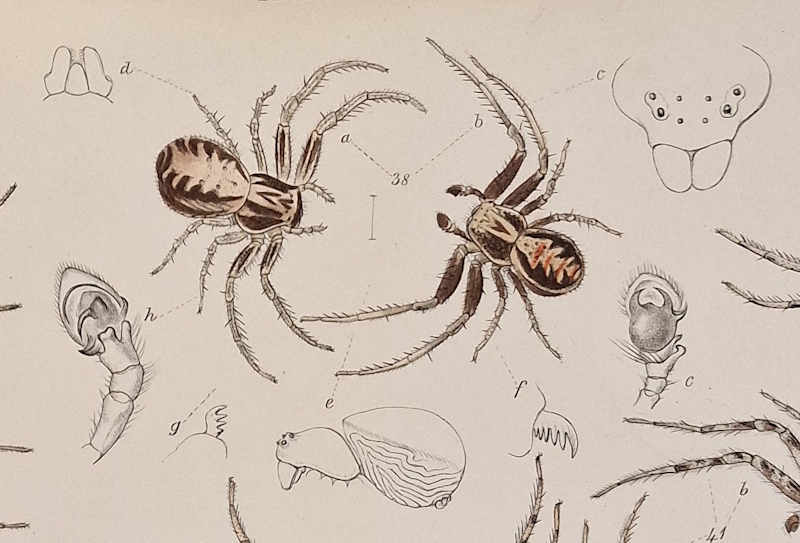

Illustration of the male and female Common Crab Spider, with various anatomical features, from John Blackwall’s History of the spiders of Great Britain and Ireland (1861-64, published by the Ray Society)

Illustration of the male and female Common Crab Spider, with various anatomical features, from John Blackwall’s History of the spiders of Great Britain and Ireland (1861-64, published by the Ray Society)

Even that figure pales in comparison to the sheer quantity of spiders we now recognise. The nineteenth century saw some significant leaps forward in the field, with works like John Blackwall’s History of the spiders of Great Britain and Ireland identifying over 300 distinct species. One of the contributors to that work was Octavius Pickard-Cambridge, a Dorset clergyman whose arachnological work was cited as the reason for his election to the Royal Society in 1887. His 1879 book, The spiders of Dorset, records over 350 species in that county alone. For all his careful observations, it turns out it wasn’t too difficult to find a few that Lister had missed, after all.

Top image: detail of the frontispiece from Aranei: or a natural history of spiders, edited by Thomas Martyn (1798)