Archival material on papers deemed unsuitable for publication by the Royal Society is being made available for the first time, as Kiera Evans reports.

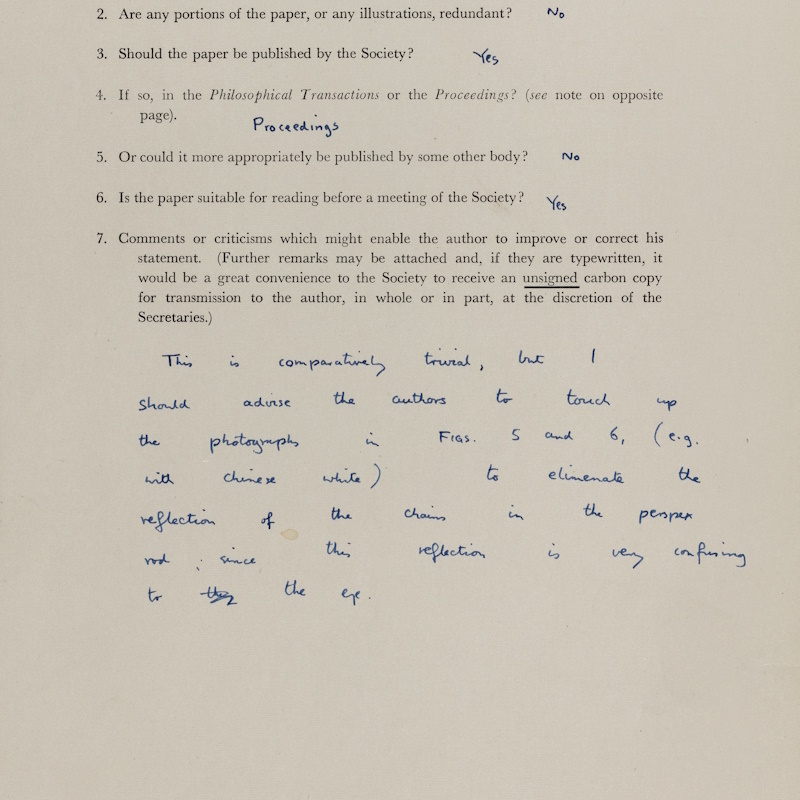

If you’re a regular reader of our history of science blog, you’ll have come across several posts discussing the Royal Society’s rich collection of Referees’ Reports. These are the means by which Fellows have assessed the suitability of scientific papers for publication in its journals, the Philosophical Transactions and the Proceedings.

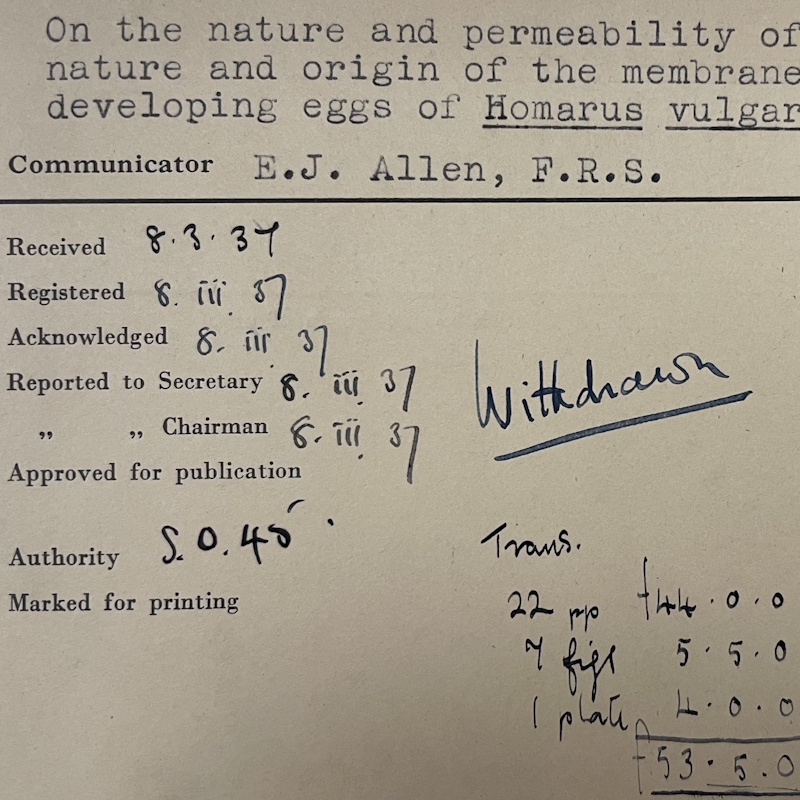

Of course, not all the papers submitted to the Royal Society ended up being published. In the 1930s, when a paper was deemed unsuitable for publication by the Society, it became standard practice for the communicator (the Fellow that had sent it in) or its authors to withdraw the submission. Material surrounding these rejected papers is being made available on our Science in the Making platform for the first time.

Something I found interesting about cataloguing this material as part of a placement in the collections was the insights it gives into the peer review process from an institutional perspective. The collection contains a number of examples of file folders, summary notes from the editorial department, and memoranda, which show how the referees were selected. Because of this, it gives a window into the logistical aspect of peer review.

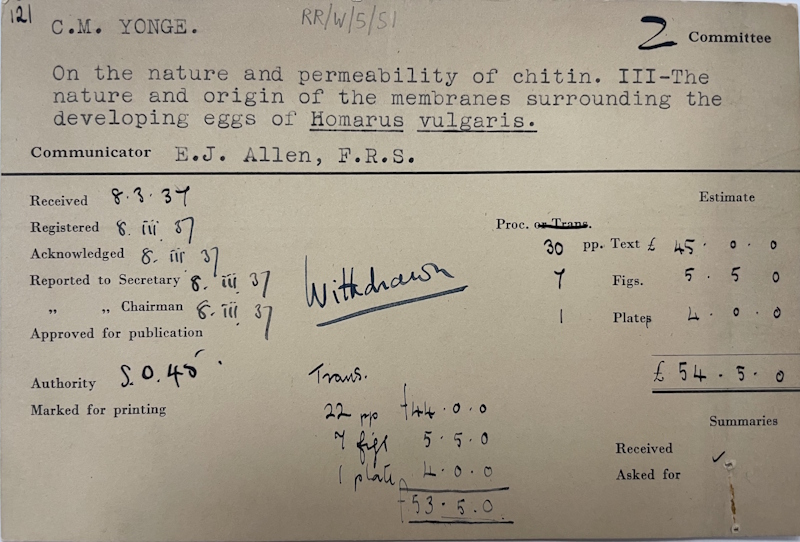

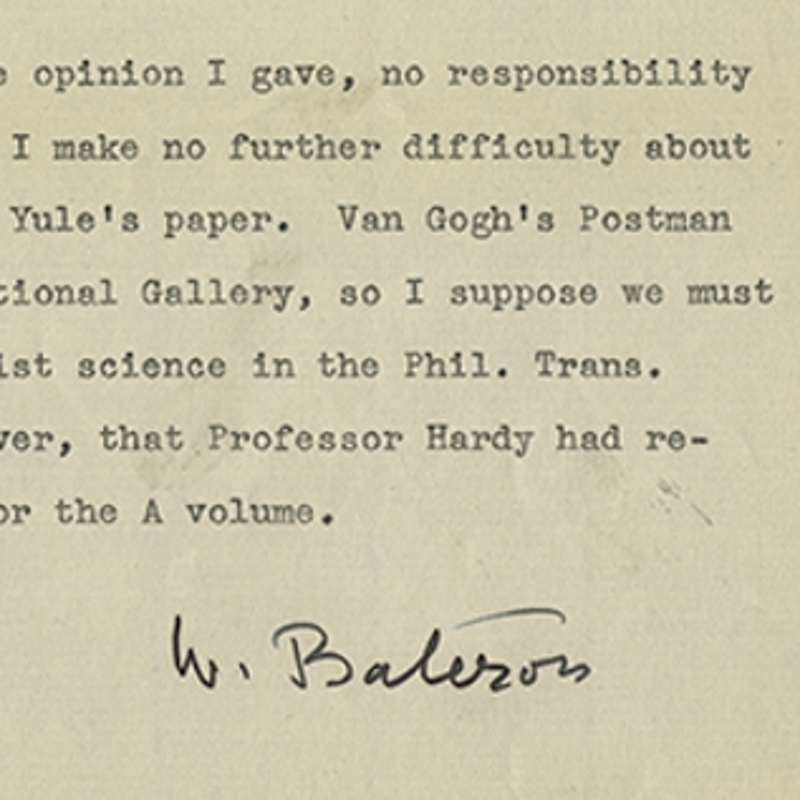

The Royal Society’s process usually involved correspondence between three or four people: the communicator, the referee(s), and the Secretary. However, it was occasionally much more complex than this, as was the case with a paper by Charles Maurice Yonge, ‘On the nature and permeability of Chitin, III’ (RR/W/5/50-67).

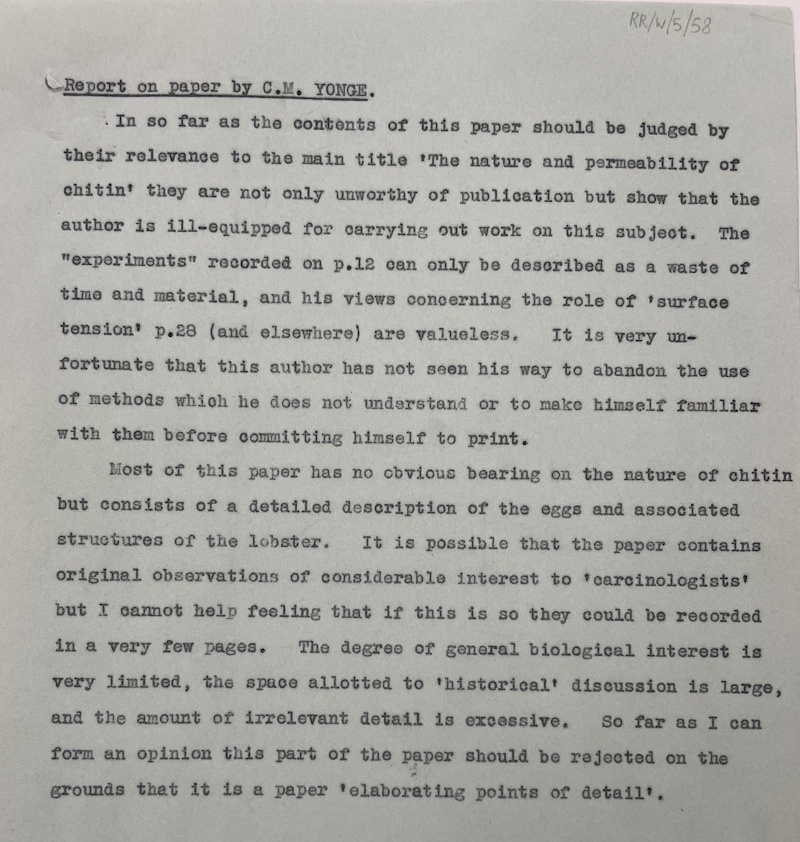

A letter sent to David Keilin by Royal Society Secretary A V Hill outlines the paper’s journey through the peer review process (RR/W/5/64). Hill begins by explaining that the piece received a scathing report from its first referee, and that when this was relayed to the paper’s communicator, he ‘discussed it with Atkins, who had, as a matter of fact, already seen the paper’ and believed it to be of publishable standard. He goes on to explain that the process then became unusually complicated:

‘Atkins wrote to me to tell me his views about the paper, and later, apparently, Gray, who seems also rather concerned, wrote to Atkins to tell him that he had been the referee, and I expect asked him to explain to Allen the nature of his judgments. At any rate Atkins, although still personally in favour of the paper, is quite willing to believe that Gray’s opinion is the more important one.’

Hill therefore asked Keilin to act as the second referee of the paper, recommending that he consult with Joseph Needham due to the cross-disciplinarity of the paper. While this level of Fellowship engagement with a single paper is uncommon, the case highlights the fact that finding independent referees with relevant expertise could, at times, be a challenge.

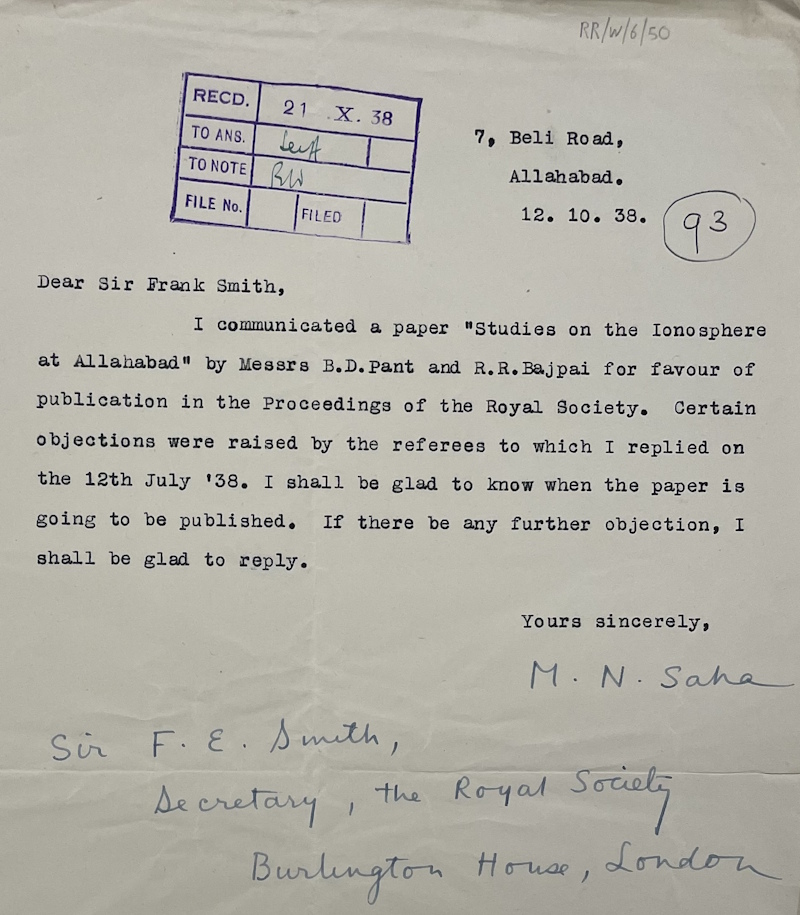

Another factor which could complicate a paper’s progress through peer review was differences of opinion on its content. The most interesting example of this that I came across was the correspondence surrounding ‘Studies on the ionosphere at Allahabad’ by BD Pant and RR Bajpai (RR/W/6/42-60), which charts an eight month-long standoff between the communicator and referees.

On 11 June 1938, the Secretary reported to the communicator, Meghnad N Saha, that the first referee had recommended against publication because ‘the really important parts of the paper have already been published' (RR/W/6/43). Saha strongly rejected this, stating ‘I have no intention of withdrawing the paper’ (RR/W/6/44). This was fed back (RR/W/6/46) to the referee, Edward Appleton, whose conclusion was unchanged (RR/W/6/47).

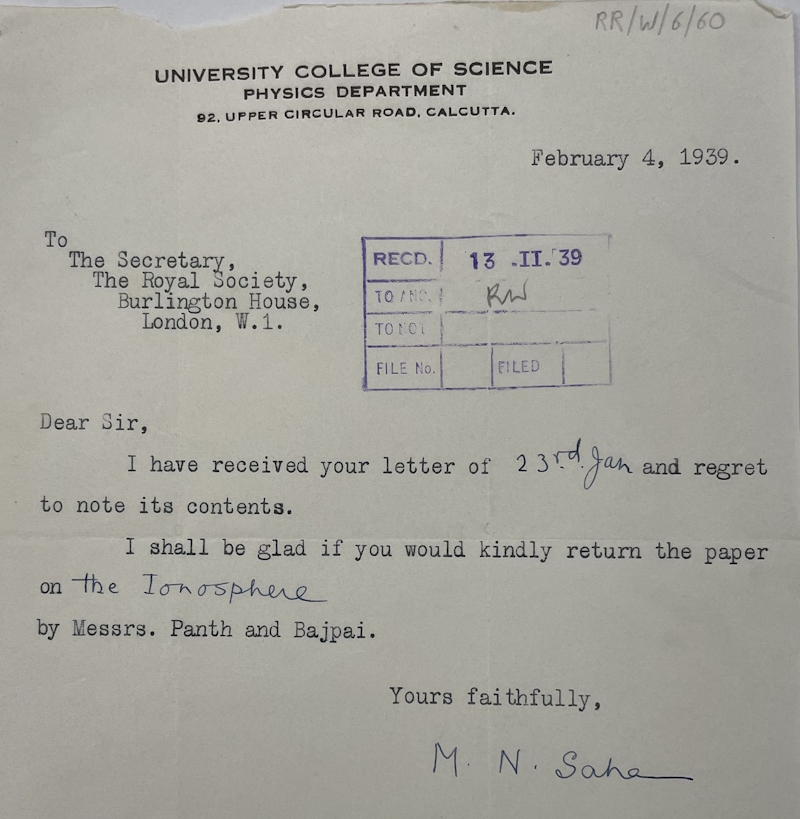

Saha remained unmoving in his refusal to accept the referee’s recommendation, and pushed for the paper to be published – even after a second referee, Thomas Eckersley, advised against it (RR/W/6/49). As a result, the unusual step of escalation to the Sectional Committee was taken. The Committee also recommended against publication, giving Saha little choice but to ask for the paper to be withdrawn in February 1939 (RR/W/6/58, RR/W/6/60).

Something I was struck by while cataloguing this exchange was the passion that Saha and the referees clearly had. Though they disagreed sharply on the paper’s suitability for publication, their shared dedication to science really comes through. I also found this case particularly interesting because it shows how the institutional process could adapt to accommodate for scientific disagreement.

These are just two examples of the stories surrounding the withdrawn papers. The Referees’ Reports might sometimes make the Royal Society’s peer review process seem clear-cut, but this material shows it could be complex and divisive.