Keith Moore tells the stories of scientists who have fallen foul of the authorities, from Galileo and Samuel Pepys to Holloway Prison inmates Thomas Pelham Dale and Kathleen Lonsdale.

One of my standing jokes at the Royal Society is that, one day, I’ll take a step back from lauding great science and design an exhibition around scientists chalking up five-bar gates on the inside of a prison cell. There are a surprising number of them to choose from and I always get excited when I find another criminal record.

The most famous is of course Galileo, placed under house arrest in 1633 for his supposed heretical (and heliocentric) views. There was quite a stir recently when a key letter from the Italian astronomer’s earlier brush with the Inquisition was rediscovered in the Royal Society’s archives. But does house arrest count? I’m looking for more hard-boiled scientific recidivists.

My latest defendant is Thomas Pelham Dale (1821-1892), a slightly obscure clergyman, but also a research partner of the chemist John Hall Gladstone FRS (1827-1902). There’s an extensive batch of Dale’s letters within the Society’s archives, and I decided to sort and catalogue them in an idle moment. It transpired that in 1880, Dale landed in ecclesiastical hot water for pretty much the opposite reason to Galileo – Dale’s offence was that he practiced ‘ritualism’ and therefore he was a little too Catholic for the Victorian Church of England. Astonishingly, Dale found himself in HM Prison Holloway (then a mixed-sex institution) for this heinous crime, before being released amid a public outcry.

Among his other sins, Dale was Librarian – clearly an untrustworthy profession – for Sion College. This preparation for a life of crime was one he shared with another of our most famous old lags, the Royal Society’s Librarian and naturalist Emanuel Mendes da Costa (1717-1791), who was incarcerated in debtors’ prison by the organisation for the embezzlement of its Fellowship subscriptions. Into this ‘Usual Suspects’ line-up we can add the Society’s first Secretary, Henry Oldenburg, placed briefly into the Tower of London in 1667 on suspicion of espionage during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Oldenburg was outdone in 1679 when two FRSs, Samuel Pepys and Anthony Deane, were accused of spying – and, in Pepys’s case, Popery as well. Now that’s a hefty charge sheet for a future President of the Royal Society.

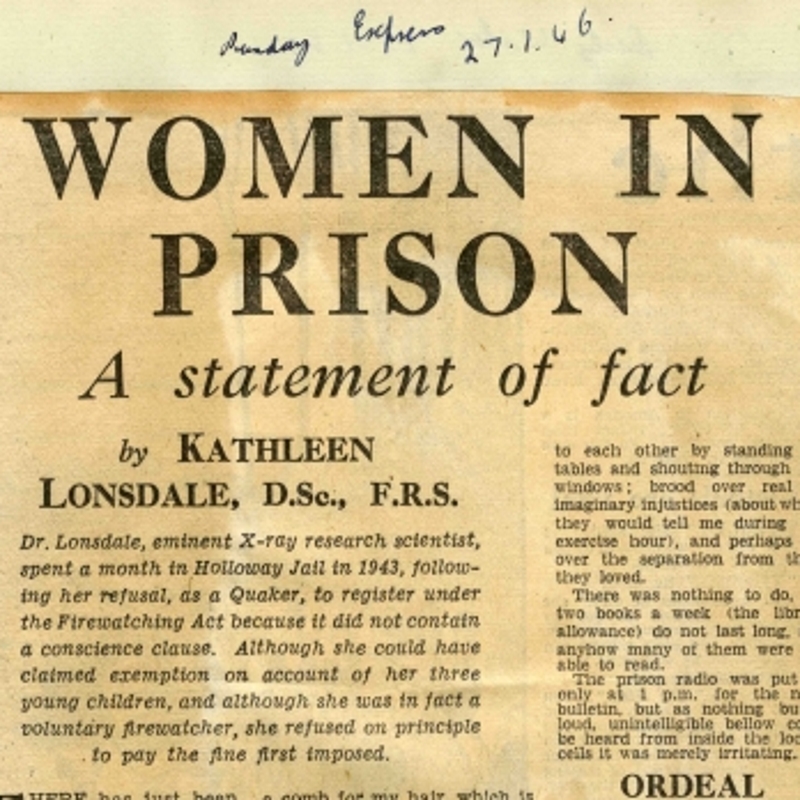

The Tower of London (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The seventeenth century was a period of huge political turmoil in Britain, and therefore gave plenty of scope for detentions. Archibald Campbell, the 9th Earl of Argyll (elected FRS in 1663) was imprisoned more than once before being executed for treason in Edinburgh in 1685, following an attempt to depose James II. On the opposite side of the justice scale, the early Fellow Sir Kenelm Digby was arrested by parliament for showing a little too much loyalty to King Charles I. It does seem that whatever the offence, you can find a counter-example without too much trouble.

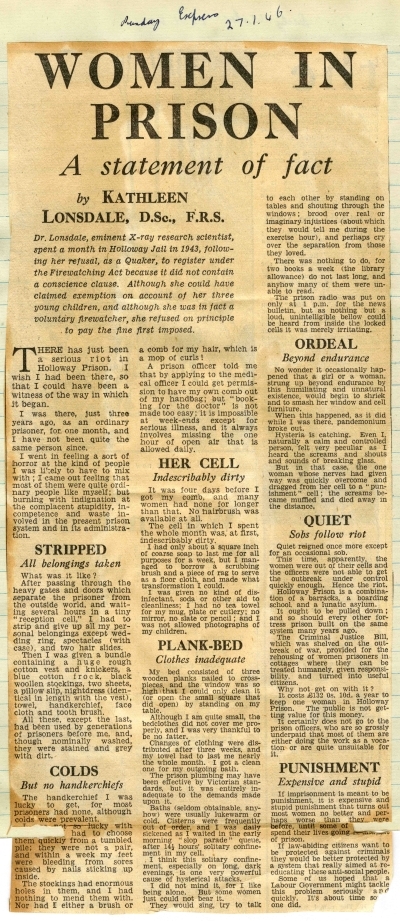

My favourite pairing of this type is from the twentieth century. The Society’s first woman Fellow, Kathleen Lonsdale, followed Thomas Pelham Dale into Holloway prison in 1943. Her offence (such as it was) was the non-payment of a small fine for declining registration in civil defence – Lonsdale was a Quaker. Imprisonment has been described as the most formative experience of her life. She continued her scientific work (Royal Society President Sir Henry Dale packed up and sent in her notes), but once released, the sometimes nervous Lonsdale discovered that she was able to speak to pretty much anyone. She began a campaign excoriating women’s prisons and seeking reform, very much in the tradition of Elizabeth Fry.

‘Women in Prison’: article by Kathleen Lonsdale FRS, Sunday Express, 27 January 1946 (Royal Society press cuttings file)

As Lonsdale entered her prison in 1943, the biochemist Samuel Victor Perry (1918-2009) was exiting his, enjoying the liberty of having escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp in Italy. A consummate escapologist, Perry was recaptured, but again managed to evade guards taking him to Germany. In echoes of Steve McQueen’s ‘Great Escape’ celluloid heroics, Perry made it to the Swiss border, but had the terrible luck of being recognised by a German guard, freshly transferred from his old POW camp. It was not to be his last escape effort – he jumped from a train in 1944 – and he was liberated, eventually, by the war’s end.

Lonsdale’s and Perry’s contrasting forms of courage are genuinely wonderful and respectively show something of the social engagement and ingenuity of scientists. And joking aside, I still think an exhibition would be a good idea – perhaps as a slightly mischievous addition to the Royal Society’s wider project on Science and the Law.