Keith Moore dips into the diaries of Sir John Herschel FRS, and finds the great man troubled by visual migraines and the turbulent Charles Babbage, but soothed by his granddaughter's Beethoven recitals.

When we think about the work done by scientists of the past, we probably don’t consider their everyday lives while they were doing it. Dipping into the diaries of Sir John Herschel, you get a pretty good idea of day-to-day Victoriana in its less-than-glorious detail. And which of his scientific colleagues was Sir Turbulent Smallman? Read on…

John Frederick William Herschel (1792-1871) was, of course, the son of William (the discover of Uranus), and nephew to the comet-spotting Caroline. Astronomy was always to be part of John’s portfolio of interests, but these also ranged from photography to chemistry, and from poetry to mathematics. As Master of the Royal Mint, Herschel was cast in the light of Sir Isaac Newton: a scientific knight for the Victorian age, familiar with the young Queen and her Consort. But behind closed doors? A very different Herschel emerges.

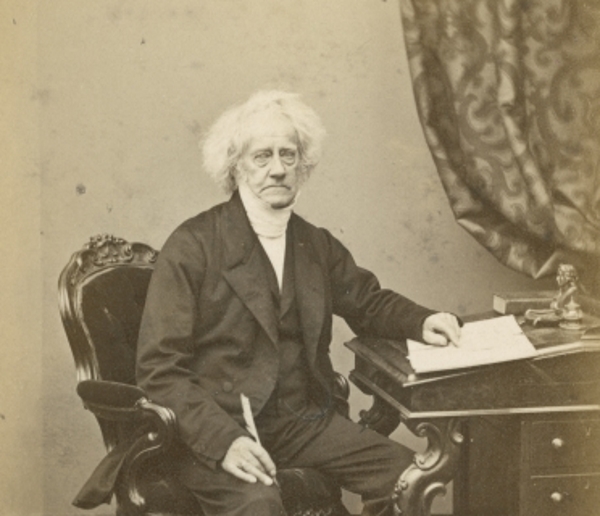

John Frederick William Herschel, by Maull & Co, undated. RS IM/Maull/002052.

To begin with, had you considered what it took to run an affluent, sprawling and semi-rural household in the 1850s? I hadn’t, but Herschel in 1848 made the calculation of residents at Collingwood House in Kent, giving a children-and-servant headcount of thirty-two. Hats off to Margaret Brodie Herschel, therefore, who must have been running the whole show; allowing Sir John to make his observations, run off to London on business, and convert his raw data into serviceable publications.

The house was a mini-community or small village into which came entertainments, frequent parties of visitors, and occasional tragedies. One servant hanged himself in the cellar; many came and went. Visitors included passing natural philosophers, artists and photographers, with friends from the world over. Herschel’s private comments could be patrician and amusingly prejudiced. He entirely approved of the transatlantic cable pioneer Cyrus Field (1819-1892) whom, he declared, was ‘a first-rate American and deserves to be an Englishman’. But the elderly Herschel entirely lost patience with the turbulent Charles Babbage, forever dragging up feuds from decades earlier. In 1851 Herschel recorded a visit to his London town house in Harley Street – ‘Babbage called & bored me to death with his loose generalities & possible explanations of imaginary difficulties’. By 1864, Herschel was raging at ‘a miserable spectacle of a man unable to contain his spite & rage when the object of it [Sir Humphry Davy in this case] is dead & buried’.

By the 1860s, Sir John’s accounts of himself were wracked by illness – debilitating bronchial infections, what he termed the ‘brown creatures’, and the attentions of medical men. In that pre-antibiotic age, chasing around his leg with scalpels to relieve abscesses took weeks and months of minor operations. Herschel administers a variety of self-medications, ranging from mustard blisters to laudanum, at one point reaching 30 drops of laudanum followed by 25 of chlorodyne, another opiate – probably enough to stop a horse in its tracks. Some illnesses at least must have been caused by poor sanitation and water supply, with frequent fevers (unconvincingly, ‘not typhoid’) invading the household. Glad to be living in the twenty-first century? Count me in.

Night-lights: an entry from Sir John Herschel’s diary, transcribed by Louisa Gordon, 1873.

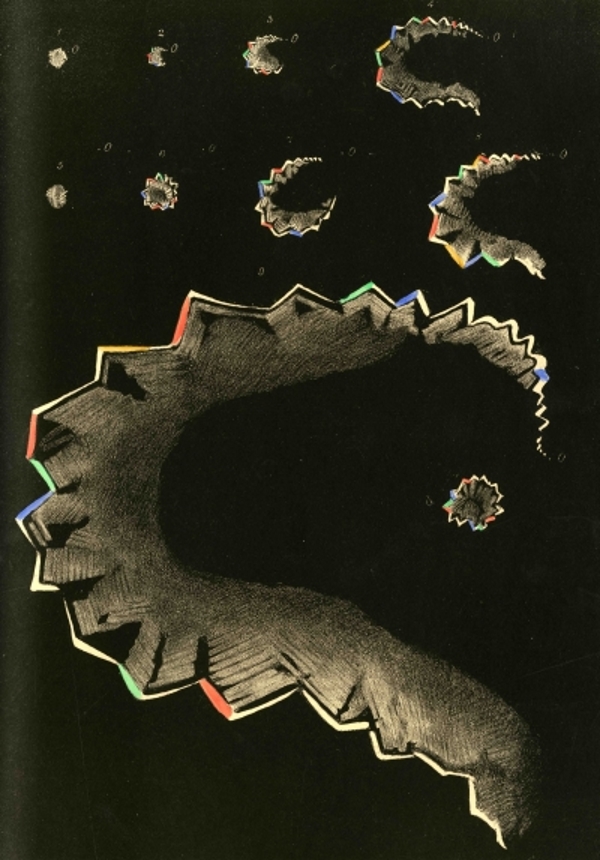

Ever the scientist, one consequence of Herschel being so body-aware was that he looked to explain some of the phenomena he was experiencing. There are long descriptions of sensory strangeness around candle flames during his many sleepless nights. These were longstanding interests. Herschel is credited with suggesting a form of contact lens to correct astigmatism, as early as the 1820s. In his diaries, the elderly astronomer routinely describes scintillating scotoma (visual migraines, sometimes known as fortification spectra). His fellow-sufferer Hubert Airy (1838-1903) incorporated Herschel’s descriptions into his Philosophical Transactions paper on the subject.

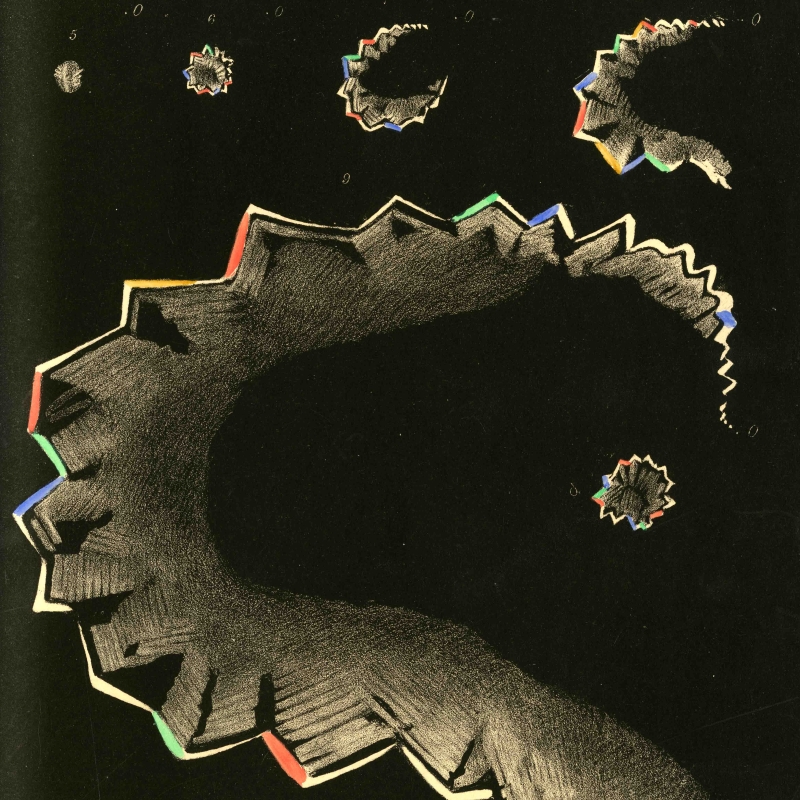

Airy-fairy: visual scintillations from ‘On a distinct form of transient hemiopsia’, by Hubert Airy, 1870.

Despite his complaints, I ended up admiring Herschel’s tenacity in struggling through the months of tedious, repetitive calculations needed to produce his star catalogues while shoring himself up against pain – and by 1870, steadied by five pounds of coca leaf from Valparaiso. There are, too, touching flashes of humanity. Sir John noted that ‘Little Lucy Gordon (aged 12) played Beethoven’s 16th sonata with hardly a trip…’ Forty years later, his granddaughter Louisa Gordon transcribed this final year diary and broke into the text excitedly, scribbling: ‘I remember his voice when he came & put his hand on my shoulder: – “I like to hear you play. Go on learning”.’ Quite charming.