Read about astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth's papers documenting his trip to a volcanic mountain range in Tenerife.

A recent enquiry led me to our Manuscripts General series for a volume I was unfamiliar with: MS/626, the ‘Tenerife Papers of Charles Piazzi Smyth’. Aware of Smyth’s position as Astronomer Royal for Scotland in the nineteenth century, but otherwise unsure what to expect, I was pleasantly surprised to find a beautifully illustrated scrapbook documenting his trip to a volcanic mountain range in Tenerife.

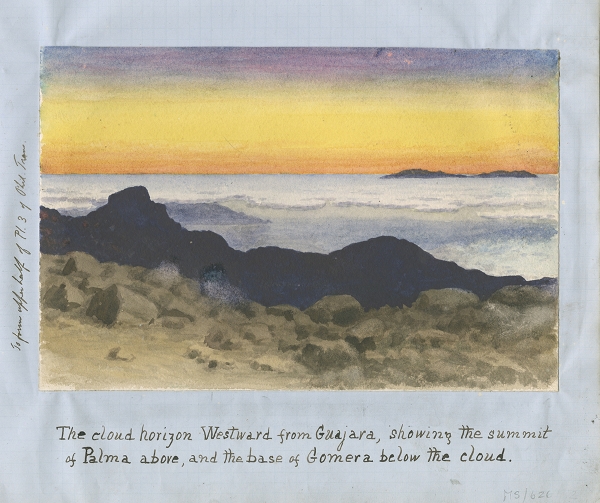

Watercolour of the ‘cloud horizon’ as seen from the first stop on Smyth’s ascent to the Peak of Tenerife at Guajara (MS/626/11)

The nineteenth century was a fascinating period for voyaging as a means of scientific intelligence-gathering, and I was keen to find out more about this particular expedition. I turned to Smyth’s paper ‘Astronomical Experiment on the Peak of Teneriffe…’, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1858. In it, Smyth described how he hoped to elevate himself to such a height that he could observe the stars and planets more clearly than from existing observatories.

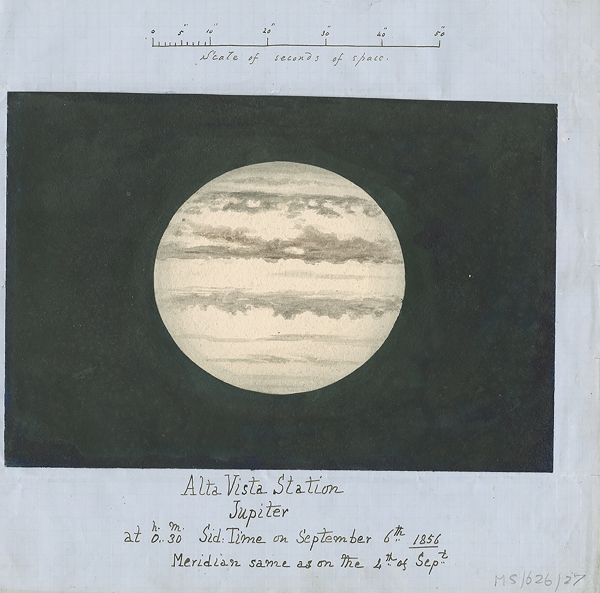

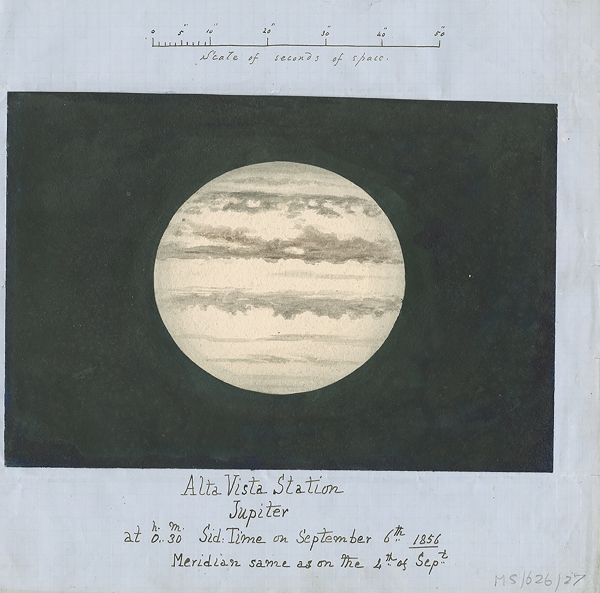

Watercolour of Jupiter as seen from the Peak of Tenerife (MS/626/27)

His efforts, he explains, were inspired by Isaac Newton’s Opticks, which stated that:

‘[Telescopes] cannot be so formed as to take away that confusion of rays which arises from the tremors of the atmosphere. The only remedy is a most serene and quiet air, such as may perhaps be found on the tops of the highest mountains above the grosser clouds.’

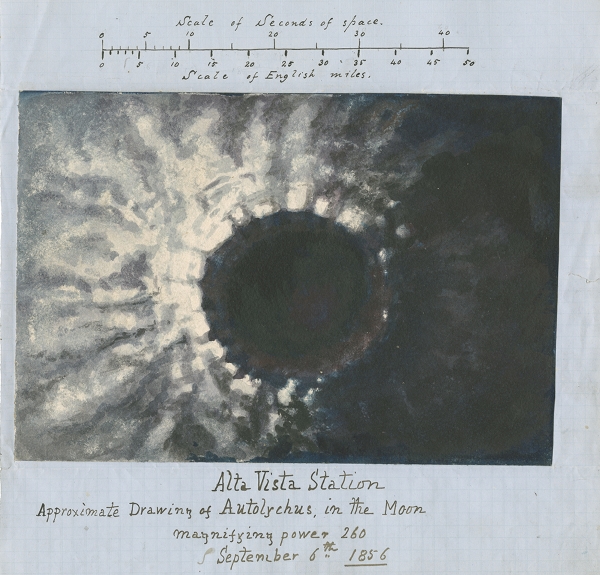

In his 1858 paper, Smyth writes that with height, and with this ‘most serene and quiet air’, came a greatly improved definition of planets and stars. He claimed that his observations of these bodies from Mount Guajara and Mount Teide (the ‘Peak of Tenerife’) ‘contrasted most favourably with the amorphous figures that the same telescope had always given in Edinburgh’. He also claimed to have seen the moon in a manner ‘very different from anything that European astronomers have had for many years past’, with his paintings of its surface an attempt to put to rest any existing doubt among geologists that the ‘circular cavities in the moon’ were craters:

Watercolour of Autolycus, a crater on the moon, as seen from the Peak of Tenerife (MS/626/29)

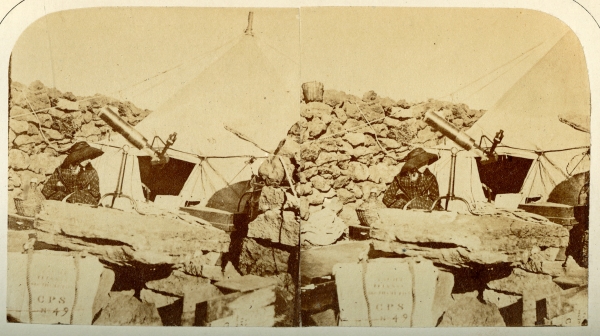

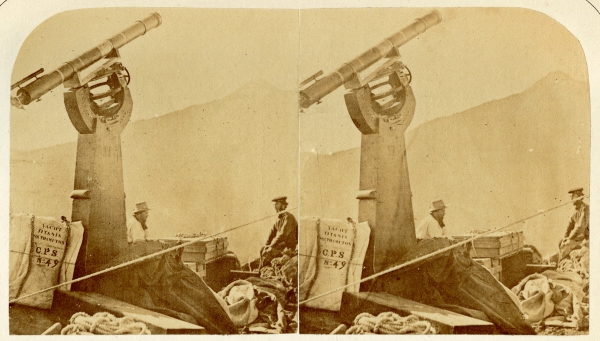

Smyth also published his results in a book, Teneriffe, an Astronomer’s Experiment (1858), rather pleasingly subtitled Specialities of a residence above the clouds. This book is an object of interest in itself, being the first ever published with photo-stereographs. Indeed, not only was Smyth painting throughout his expedition, he was also utilising photography to record the progress of his work. Like his peers, Smyth had followed this new art form with interest. He must also have practised it to some degree, since John Herschel commented in the run-up to the trip that:

‘As Mr. Smyth is an expert photographer, he should be provided with an apparatus for obtaining photographic impressions of everything worthy of record’

Smyth was therefore furnished with a portable form of collodion apparatus suitable for working on stereoscope plates (for more on stereoscopic photography, see our earlier blog posts from August 2018 and July 2019). Over the course of the trip, he created 200 photo-stereographs.

Photo-stereograph 4, from ‘Teneriffe, An Astronomer’s experiment’, captioned ‘Tent Scene on Mount Guajara, 8903 Feet High’ and featuring Smyth’s wife Jessica ‘Jessie’ Piazzi Smyth

Photo-stereograph 5, from ‘Teneriffe, An Astronomer’s experiment’, captioned ‘Sheepshanks Telescope first erected on Mount Guajara, the Peak of Teneriffe in the distance’, and featuring Smyth who sits at the foot of the equatorial mount

We know that Smyth had certain of these photo-stereographs copied in order to illustrate his book. They depict everything from his apparatus, to the atmospheric phenomena he observed, to the general ecology of the mountain range through which he travelled.

This approach places Smyth’s Teneriffe firmly in the category of ‘photography incunabula’: books, dating largely from the 1840s to the 1880s, illustrated by hand-mounted photographs. Its significance in the history of photography is therefore twofold. Not only is it the first book to be published with photo-stereographs, but it is also a very early example of photographs appearing beside the printed word. It can be considered a forerunner to the field of widespread photographic publishing, which, thanks to the development of photomechanical printing processes, would blossom in the late nineteenth century and never look back.

Smyth’s ‘Tenerife Papers’ can be viewed online via our Science Made Visible platform, and sample images have recently been uploaded to the Picture Library (with more to come – watch this space!)