What can Royal Society archives reveal about plans to feed the British populace during First World War food shortages?

While browsing our catalogue, as one does, my eye fell on a file entitled ‘Substitute foods from the West Indies’ (MS/527/2/14). Given my interest in Caribbean and colonial history, I was immediately intrigued. I glanced through the file and was surprised to find heated debates about the usefulness of plantain flour. Looking further, it became clear that these were part of a wider discussion about how to feed the British populace during First World War food shortages.

This file is part of a series focused on the Food (War) Committee of the Royal Society, and covers subjects from rationing to the prevention of scurvy. The Food (War) Committee acted in an advisory capacity to the Ministry of Food, and so in the archives we have several files dealing with such issues. While I had often listened to my gran’s tales of rationing and the lack of sweets and chocolate during the Second World War (and hence understood her refusal to listen to lectures about sugar intake), I didn’t actually know much about what was done to fill the gaps when certain foods weren’t available during the World Wars, or the key role played by the colonies.

As much as Britain needed the produce, it wasn’t always as simple as taking what they could get. There needed to be investigation into what could be produced and shipped on such a large scale, as well as what would be acceptable to the British people. The Society received suggestions for food substitutions from a range of informants, and subsequently undertook investigations into whether they would actually work.

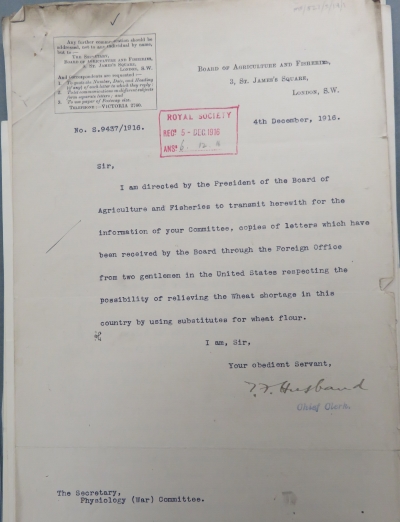

Letter to the Physiology (War) Committee (MS/527/2/14/1)

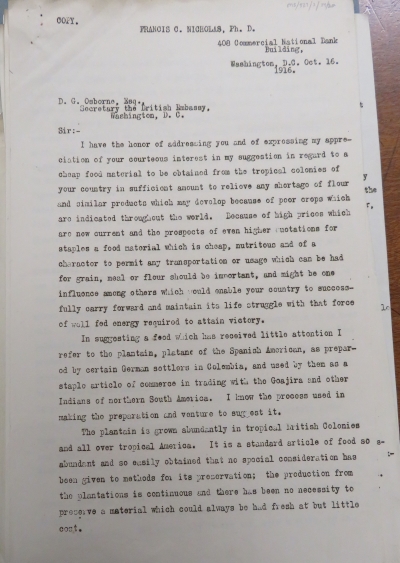

In 1916, a key issue was wheat. One Francis C. Nicholas PhD wrote to suggest that plantain would be the perfect replacement for wheat flour as it was cheap and easy to obtain (MS/527/2/14/2), and suggested Frank Cundall of the Institute of Jamaica as a useful middleman with connections to plantain suppliers. Interestingly, I’ve come across Frank Cundall before: while working at the V&A Archives, he popped up a number of times in correspondence related to the Institute of Jamaica. This just goes to show how extensive colonial administration was. The Institute, which was nominally ‘For the Encouragement of Literature, Science and Art in Jamaica’, actually had a key role in imperial matters, including food supply whenever necessary.

Despite Nicholas’s enthusiasm for plantain and its apparently unbounded potential, others were not so convinced. Sir Sydney Oliver stated that:

‘Mr. Nicholas evidently knows very little of the subject about which he writes. His statement that the constitution of plantain is similar to eggs is as absurd as his representation that no other food product has so high a ratio of sustaining material.’ (MS/527/2/14/6)

Letter from Francis C. Nicholas (MS/527/2/14/2a)

As well as the problems mentioned above, there was also the issue of whether the British people would actually like the different types of food on offer. One letter states that ‘with regard to the sweet potato some amount of prejudice would have to be overcome’ (MS/527/2/14/68). While there is the sense from these discussions that the West Indies must have been overflowing with surplus food in order to supply Britain with this variety of produce, a letter to Horace T Brown FRS explained that plantain in particular was grown on a small scale for the needs of the local population, although banana was plentiful (MS/527/2/14/7).

Furthermore, a letter from Algernon Aspinall of the West India Committee states that the West Indies were at the time ‘producing insufficient food for their own requirements’ and importing many items (MS/527/2/14/17). Aspinall also suggests that rice production in British Guiana could be expanded instead, but more workers from the ‘East Indies’ would need to be brought over. The importation of workers from Asia, and particularly India, was common up to the early twentieth century in the British Empire, after the abolition of slavery led to a lack of cheap labour. The system of forced labour was called indenture, and was banned in 1917, so it is interesting that Aspinall suggests this in the same year.

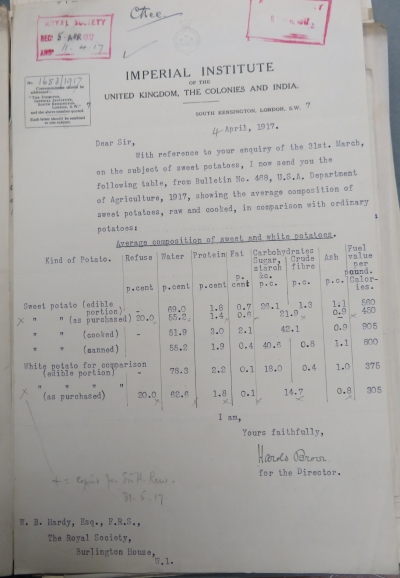

The nutritional value of potatoes (MS/527/2/14/33)

So why was the Royal Society involved in the first place? In reaction to the First World War the Society created a War Committee in 1914. The Food (War) Committee existed in various incarnations between 1915 and 1919, and consisted of medical, agricultural and economic scientists. The discussions on food replacements placed a lot of focus on the nutritional value of certain foods, as well as the economic and agricultural factors involved in importing them, and the knowledge of the Royal Society scientists was invaluable for this.

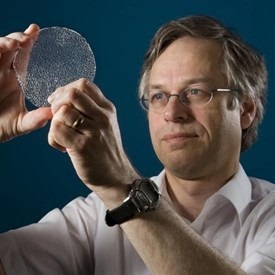

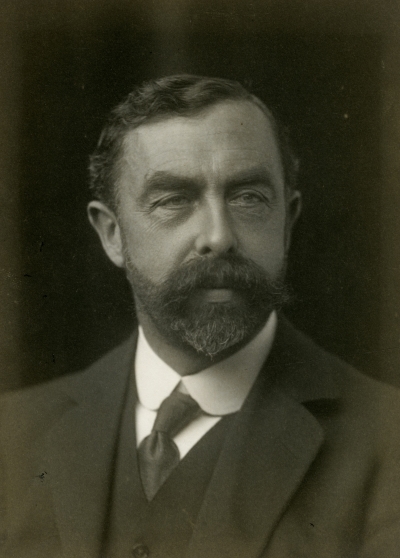

Sir William Bate Hardy FRS, by James Russell and Sons, 1922 (IM/GA/Russell/001944)

In a 2002 article, Andrew J. Hull described this period as a time where scientists were pushing to have more of an impact on government policy and to be better funded and utilised by the state. In 1917, the Biological Secretary of the Royal Society, Sir William Bate Hardy FRS, heavily criticised the Ministry of Food in a memo sent to Number 10, claiming that the Ministry of Food’s public pronouncements were ‘in flagrant opposition to the elementary principles of economics and physiology’ (MS/527/9/11/35). He was apparently dissatisfied by the impact which the Food (War) Committee had been able to have on policy.

Although it doesn’t seem that plantain flour made a debut in Britain, the files of the Food (War) Committee highlight an interesting relationship between government, colonialism, public science and public health during the First World War.