Read more about the science behind rationing and nutrition during the Second World War.

We’re only a couple of weeks into the New Year and already the holidays seem like a distant memory. After over-indulging on festive food, I’m probably not alone in thinking about eating more healthily in 2020. Some of you might even be joining in with Veganuary this year, though it’s not always easy to stick to a new diet when temptation is everywhere. If you were alive in Britain during the Second World War, however, you didn’t really have a choice.

The eighth of January 1940 marked the introduction of food rationing in Britain, as the war began to limit supplies. Restrictions were first imposed on bacon, butter and sugar, but by late 1942 more or less all food in the country was rationed. Although necessary, the government was naturally concerned about the health impact on the population. They needed to ensure that members of the public were still getting a balanced diet, with food to keep them fit and able to work and support the war effort.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, Elsie Widdowson and Robert McCance, two nutritional scientists in Cambridge, were planning an experiment to determine just what that balance was. Regular Radio 4 listeners may have heard Dr Venki Ramakrishnan, President of the Royal Society, talking about their work on Woman’s Hour earlier this month. Last year, we received a collection of their papers from the Medical Research Council, following the closure of the Elsie Widdowson Laboratory in December 2018.

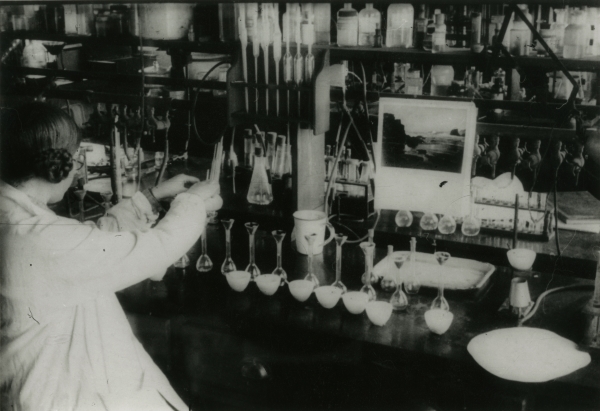

Widdowson and McCance started working together at King’s College Hospital in 1933. Widdowson had just finished her PhD and was working in the hospital kitchens as part of her diploma in dietetics, while McCance was carrying out research into the carbohydrate content of meat and fish. Speaking at the Neonatal Society in the 1980s (MS/934/1/6/3), Widdowson recalled their first meeting:

‘I often saw a then white overalled young man come into the kitchen and put joints of meat into one of the ovens and come back later and take it out again … I plucked up courage one day and spoke to him, and he invited me to visit his small laboratory. I did this, and when he told me about his previous study on carbohydrate in fruit and vegetables I at once told him his results for fruit would have been too low, for boiling with acid would have destroyed some of the fructose… Instead of being annoyed as he might well have been, he said he would try and get a grant for me to come work with him.’

Elsie Widdowson working in the laboratory in the 1930s (photo courtesy of the Medical Research Council)

The Medical Research Council agreed to fund Widdowson’s work with McCance, and after seven years of research they published the first edition of The Chemical Composition of Foods in 1940. This landmark book on nutritional science contained the first complete nutritional tables compiled about British foods. These have been updated numerous times since, though Widdowson and McCance’s work still forms the core of the nutritional data. Doctors and dietitians refer to their work to this day; a seventh revised edition of Chemical Composition was published in 2014.

Away from nutritional tables, the outbreak of the war got Widdowson and McCance thinking about how to help. Widdowson explained their proposal in her 1980s lecture: ‘we in common with many other people felt we ought to do something … so anticipating that there would be a shortage of food we made an experimental study of rationing’.

They knew that if Germany cut off British ports, the country could not rely on imports and would have to sustain itself. Based on the likely availability of food in this scenario, Widdowson and McCance calculated the available weekly rations for an individual. They then planned to stick to this diet for three months, as did five other volunteers. The weekly portions were meagre, to say the least: 1lb (about 450g) of meat and fish, 5oz (about 140g) of sugar, 4oz (about 110g) of fats, 4oz of cheese, and a single egg. 6oz (about 170g) of fruit was permitted, as long as it was not imported. Finally, milk was limited to a quarter of a pint per day. Fresh British-grown vegetables and bread were not rationed during the experiment, so you could at least eat all the potato sandwiches you wanted.

There was some expectation that a diet this restricted would be entirely unsustainable. These rations represented less than half, and in some cases less than a third, of the average weekly consumption in Britain before the war begin. In reality, Widdowson recalled, ‘we found the diet rather filling, containing as it did so much bread and potatoes and so little fat and sugar’. At the end of the experiment, the group spent ‘a glorious fortnight in the Lake District in January 1940, still living on the rations. We walked and climbed as we have never done before or since’.

Elsie Widdowson (centre) hiking in the Lake District in January 1940 (photo courtesy of the Medical Research Council)

This demonstrated that a properly rationed diet could still provide people with enough energy to work effectively and remain healthy: ‘The principle that we adopted of having bread and vegetables unrationed was important because it ensured that those with high energy requirements would obtain enough’. These findings were a key influence behind the government’s decision to leave bread and vegetables unrationed during the War, though supplies of both were still limited.

Widdowson visiting McCance during his time in Uganda, 1967 (photo courtesy of the Medical Research Council)

This experiment was not Widdowson and McCance’s only influence on the wartime diet. In 1941, based on their advice, the government introduced legislation to mandate the fortification of bread with calcium. This ensured people got enough of the mineral in their diet, despite the restrictions on dairy products. The pair continued to work together long after the war, and both scientists were later elected as Fellows of the Royal Society, McCance in 1948 and Widdowson in 1976. Despite their importance to the development of nutritional science, however, I would recommend avoiding their ration diet. Unless you really like potatoes.