Find out about the first medical autopsy carried out on an ancient Egyptian mummy.

A little while ago I wrote a post about the Duke of Norfolk’s Ancient Egyptian mummy, which he donated to the Royal Society in 1667. At the end of the blog, I mentioned Augustus Bozzi Granville, a later Fellow with an interesting story of his own. I’m now returning to this theme to unwrap the story of the first full medical autopsy carried out on an ancient Egyptian mummy.

Granville was elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1817 at the age of 34, and his life up to that point had certainly been eventful. Born into the wealthy Bozzi family in Milan in 1783, he studied medicine at the University of Pavia, where his teachers included Alessandro Volta, who at the time was working on the development of the voltaic pile. Graduating in 1802, during the time of Napoleon’s rise to power, Granville feared conscription into the French army, so he left Italy and spent the next few years travelling in Europe and working as a surgeon in the Turkish navy. He joined the British Royal Navy in 1807, and after his retirement in 1813 adopted his English grandmother’s surname, Granville, and set up a medical practice in London.

Photograph of Augustus Bozzi Granville from the Royal Society Collections (IM/Maull/001742)

One of Granville’s patients was Sir Archibald Edmonstone, who had journeyed to Egypt in 1819 to explore the great desert, an account of which was later published in 1822. However, when Edmonstone returned to London in 1821 he was in poor health. It was while being treated at Granville’s clinic that he happened to mention the mummy he had brought back to England, still in its coffin, from a village near Luxor, the site of the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes. Granville expressed an interest in unwrapping and studying it, and Edmonstone agreed to his proposal.

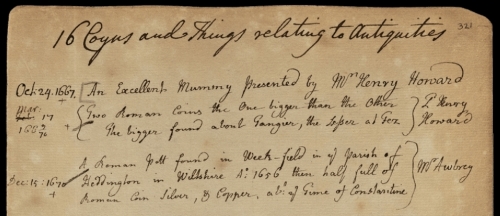

What set Granville’s work apart from similar studies of the time was his decision to treat the examination like a medical autopsy. Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was a great interest in Ancient Egypt among western cultures, and this fed a demand for mummies to be brought out of the country for study. However, they tended to be viewed as ancient artefacts, rather than the remains of a once-living person. When the Royal Society’s Repository Committee created a catalogue of the museum collection in the early 1730s, they listed Norfolk’s mummy under the heading of ‘Coyns and Things relating to Antiquities’, rather than with the ‘Parts of Human Bodies’.

'An Excellent Mummy presented by Mr Henry Howard’ (MS/416)

Granville carried out the autopsy over a period of six weeks, working at home and usually accompanied by one or two of his medical and scientific friends. It was first necessary to remove the mummy from its outer case and take off the bandages, and Granville’s surgical background allowed him to make some interesting observations as he did so. In his paper, he remarked that the bandaging was ‘most skilfully arranged, and applied with a neatness and precision, that would baffle even the imitative power of the most adroit surgeon of the present day’.

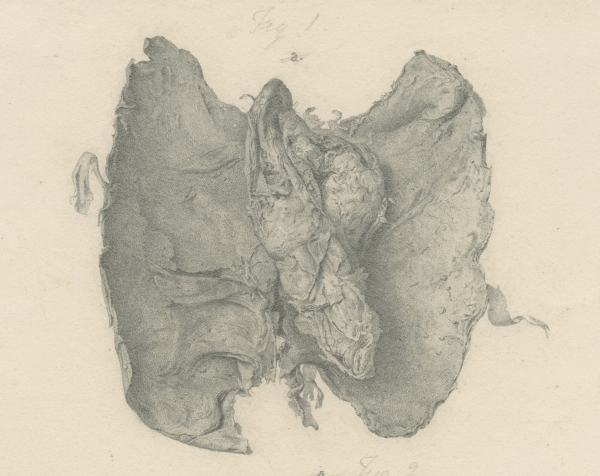

With the bandages removed, Granville was pleased to see that the soft tissue of the body had been remarkably well preserved. Upon opening the abdomen of the cadaver, it quickly became apparent that most of the internal organs had not been removed during the embalming process. Granville described the heart as being ‘found suspended, in situ, by its large blood vessels, in a very contracted state, attached to the lungs by its natural connections with them’. The presence of the organs was a stroke of good fortune, as they provided important clues to the life and final illness of the deceased.

Drawing of the heart, still attached to the lungs (PT/73/11/19)

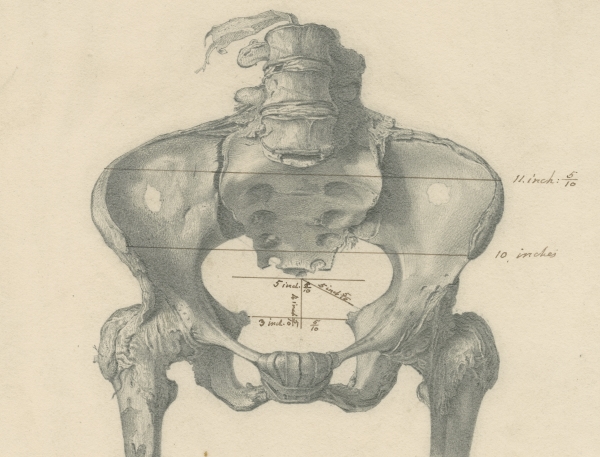

Granville set about applying his considerable medical knowledge to draw some interesting conclusions about the mummy. Clearly a woman, a noticeable thinning of the pelvic bones led Granville to suggest that she had borne children and died between the ages of 50 and 55. Finally, he concluded that ‘the disease which appears to have destroyed her was ovarian dropsy’, via the discovery of a large growth on the right ovary which he believed to be cancerous.

Drawing of the pelvis, with various measurements taken (PT/73/11/16)

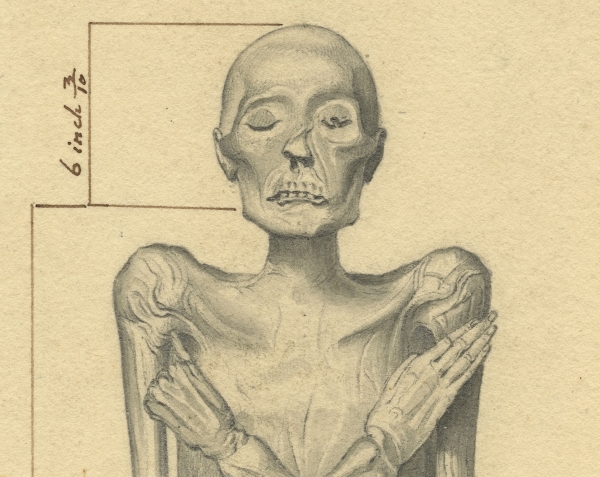

In order to better record the results of the autopsy, Granville hired an artist named Henry Perry, who produced a series of detailed drawings of the mummy, including the images used to illustrate this article. Granville presented these to the Royal Society along with his lengthy manuscript, which was subsequently published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1825; the original paper and plates remain safely stored in the Royal Society Archives.

Following the publication of the article, Granville was invited to give a number of public talks about his work. He seems to have enjoyed putting on a performance at these events, displaying some of the mummified organs in a specially commissioned cabinet. At the Royal Institution he presented candles made from a waxy substance found inside the mummy. Granville had incorrectly concluded that submerging the body in wax was part of the embalming process, but the reality was rather more gruesome: it was decomposed body fat. I don’t expect many scientists can claim to have given a lecture by human candlelight…

The British Museum eventually purchased the remains from Granville in the 1850s, and took possession of the coffin lid, bandage samples and some of the mummified organs. These were left in storage until the 1980s, when they were rediscovered and probed using the latest scientific techniques. Analysis of the hieroglyphs on the coffin lid revealed the woman’s name to be Irtyersenu, and carbon-dating indicated she lived around 600 BC.

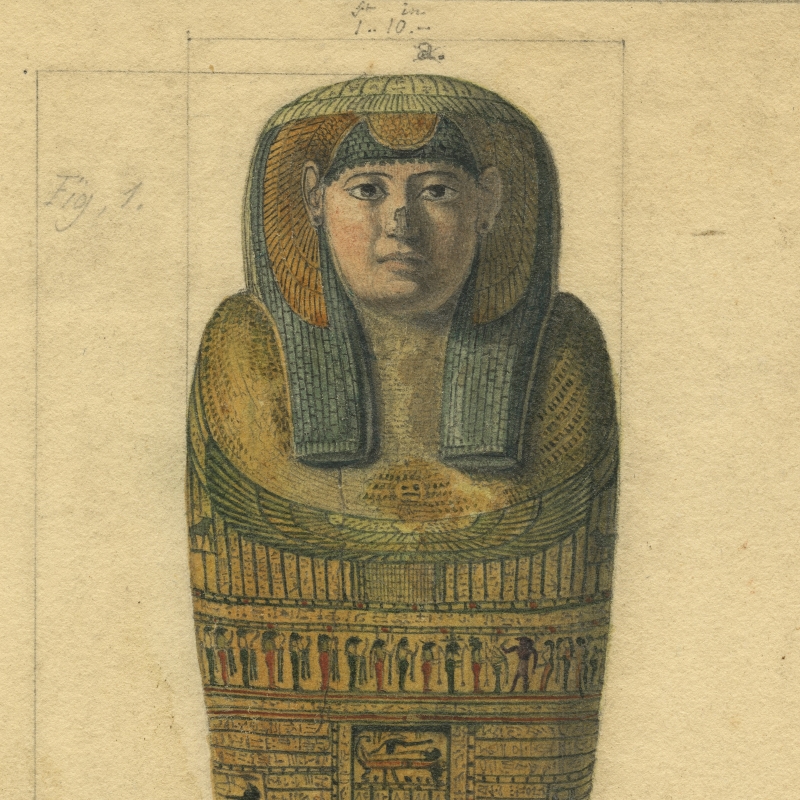

Colour drawing of the lid of the coffin that contained Irtyersenu’s mummy (PT/73/1825/248)

Further work was carried out quite recently, when a research team set out to determine whether Granville’s assertions about the cause of death had been correct. DNA testing proved that the supposedly cancerous growth was actually a benign cyst; instead, there was evidence of a widespread tubercular infection which would almost certainly have been fatal. The team’s results, fittingly enough, were published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B in 2009. Still, it’s hard to fault Granville for the incorrect conclusions of his autopsy, and his careful preservation of the remains has enabled modern science to shed more light on life in Ancient Egypt 2600 years ago.

The face of Irtyersenu’s mummy (PT/73/1825/249)