Louisiane Ferlier finds a recipe for turnip bread, and a description of Moroccan cuisine by Royal Society clerk Jezreel Jones, in the early days of our Philosophical Transactions journal.

Food and beverages were regular topics of discussion in the early days of the Royal Society. Despite English agriculture being the most productive in Europe by the end of the seventeenth century, the British Isles still experienced food shortages, and correspondents to the Society attempted to address the issue with practical solutions.

Long before the great plantain debate of WWI, in 1693 Samuel Dale, an apothecary and amateur botanist, advised the Royal Society that due to an increase in the price of grain, people in Essex had taken to using peas, barley and turnips as a substitute for flour in bread. His recipe for turnip bread, transcribed in modern English, bears a strong resemblance to methods for making the more common potato bread:

‘Take peeled turnips, boil them in water until they are soft or tender, beat or pound them very fine and small with their weight of wheat-meal. Add salt and warm water to knead in a dough or paste, leave a while to ferment, shape and bake.’

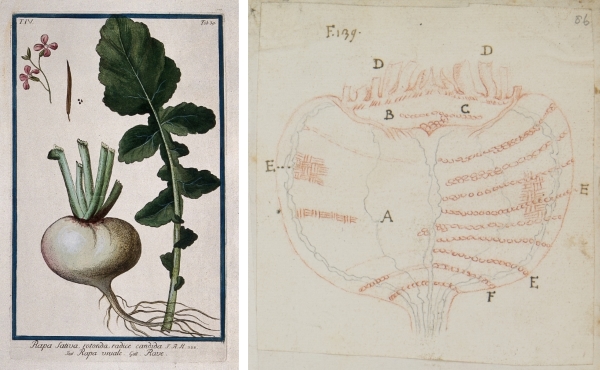

Turnips: (L) Turnip or sarson (Brassica rapa L.): root, leaf, flowers, fruit and seeds. Coloured etching by M. Bouchard, 177-. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International Collection (CC BY 4.0); (R) Red chalk drawing by Marcello Malpighi, 1678.

Dale promised that ‘only to dainty and nice palates are the turnips a little, and but a little, perceived’, which might disappoint Baldrick but should reassure the rest of us. It’s good to remember that the yeast and flour shortages experienced by some home bakers during the COVID-19 lockdown in the UK have not amounted to a subsistence crisis (although an estimated 1 to 3 million people do suffer from food insecurity), but it is interesting to consider what alternatives have been used throughout history.

If turnip bread isn’t quite to your taste, I suggest you turn instead to a long and fascinating account of Moroccan cooking and eating published by a Royal Society clerk named Jezreel Jones.

In 1698, Jones, a scholar of Arabic, was sent on a ‘discovery of Africa’ by the Royal Society’s Council. The scientific instructions to this one-man expedition seem to have been to collect natural specimens and observations, as he sent back plants and animals to Hans Sloane and James Petiver. Jones appears to have only produced one written report for the Society, an ‘Account of the Moorish Way of Dressing their Meat (with other Remarks) in West Barbary, from Cape Spartel to Cape de Geer’.

We know that Fellows frequently published enquiries in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions journal to obtain information on the meteorology, geology, botany and zoology of different parts of the world, and that pseudo-ethnographic articles relating the customs of indigenous people were sent regularly by correspondents following the routes of British colonialism. However, this article only contains a few remarks on the flora and fauna of northern Morocco, and mostly reads as an account of the wonderful meals Jones shared with locals along the coast, from pickled fish for breakfast to fox and camel for supper.

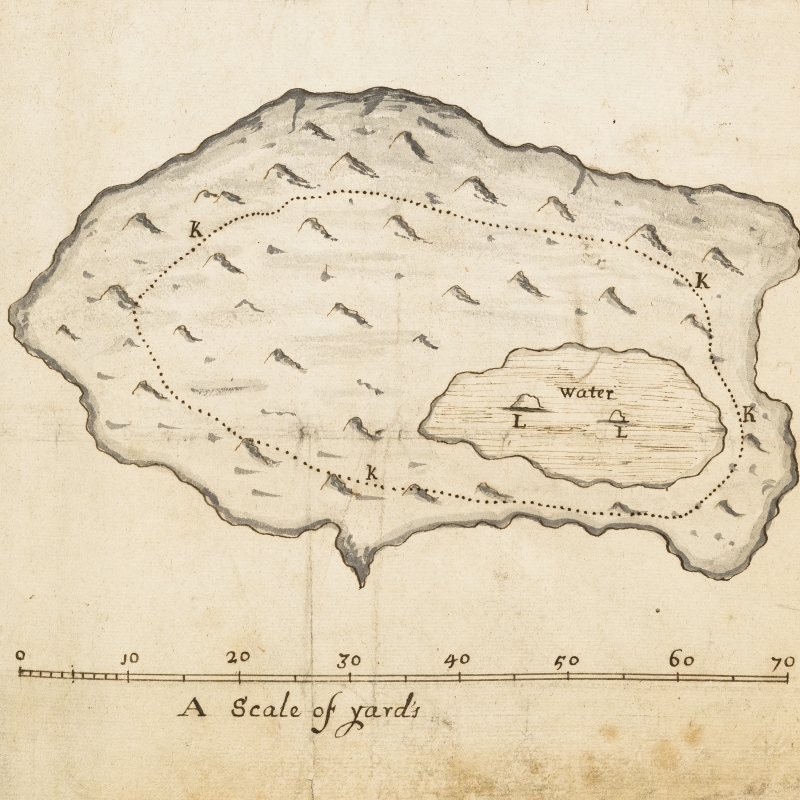

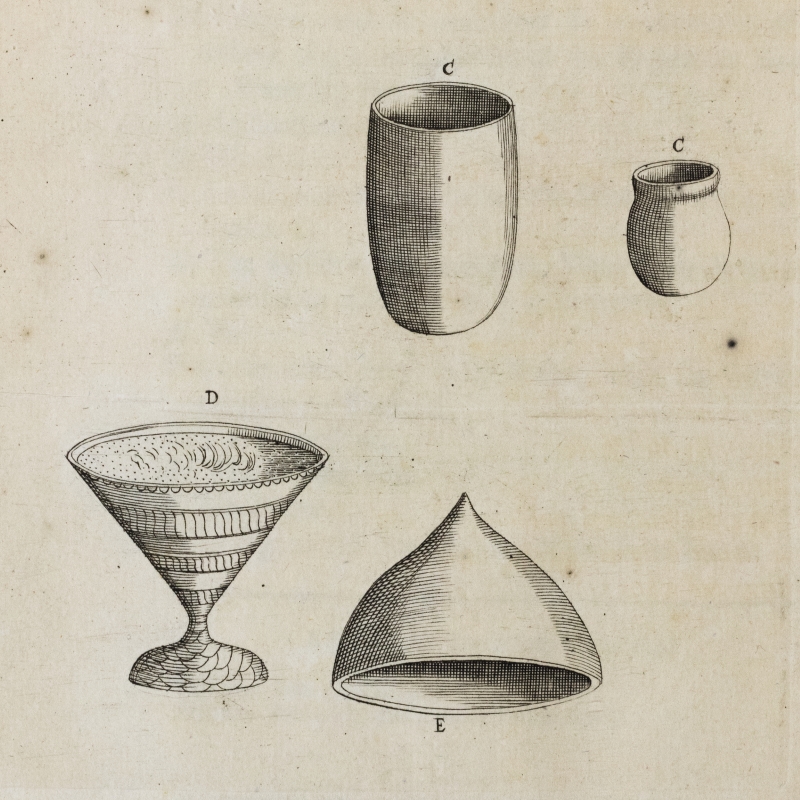

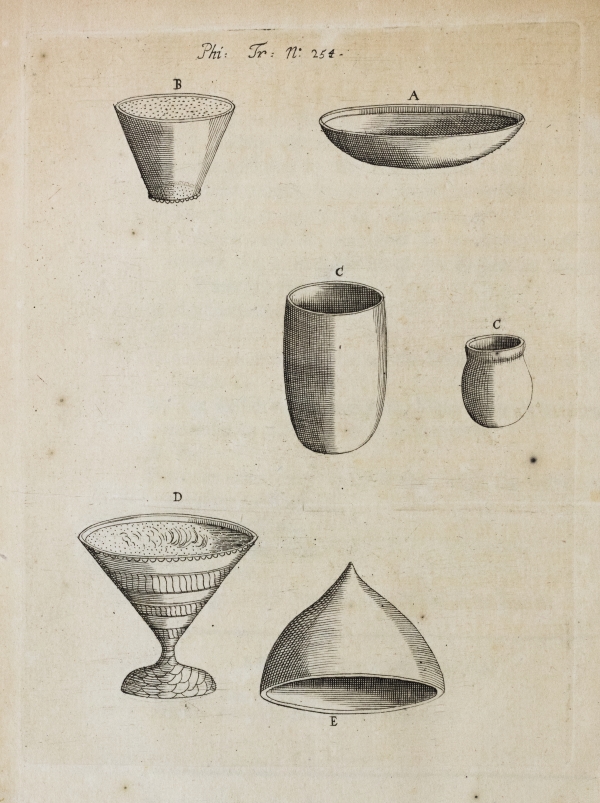

I am quite intrigued by the many types of honey Jones got to sample, but the highlight of this article is certainly the tajine recipe. The illustration sent by Jones depicts the earthenware pot used in its preparation:

Cooking implements from Morocco by Jezreel Jones, 1698

After explaining how couscous is made, using wheat, barley, millet or corn, Jones explains that meat is stewed in the closed tajine pot, with couscous steaming above it in a colander. I was quite surprised to read that the ‘good store of spice, as ginger, pepper & saffron’ was added as the dish was being served rather than cooked with the meat.

While the focus is largely on meat (and although the kebab recipe on page 252 sounds divine, I must warn that his description of catching and cooking the ‘Princely’ hedgehog is off-putting), vegetarians can still feast on the warm bread, the ‘hasty-pudding’ (a porridge), and ‘three of four sorts of pumpkins, macaroons, almonds prepared many ways, raisins, dates, figs dry and green, excellent melons of two of three sorts, and water melons, pomegranates, apples, pears, apricots, peaches, mulberries, plums, cherries, grapes’ as well as on ‘salating’. Jones describes his article as a ‘tiresome and frivolous Discourse’, but I disagree: the account gives inspiring tips on which spices and herbs to use for your morning breakfast, and offers a glimpse of the warm welcome Jones encountered throughout seventeenth-century Morocco.

The Philosophical Transactions have many more food preparation tips in store, but if you’re on the hunt for historical recipes that are actually tried and tested, I can recommend Marjory Szurko’s Sweet Slices of History. Perhaps my next post will look at some of the dozens of gardening articles in our journal, to ensure that we all keep cultivating our gardens in these troubled times.