Frankie Chappell descends into our archives to explore the dark legend of Pen Park Hole in Bristol.

I grew up in Bristol, and can tell you that it’s full of beautiful landscapes, views and hidden gems. I distinctly remember stumbling across caves in Blaise Castle Estate, and the rock slide in Clifton. One mystery I have only just discovered, thanks to the Royal Society’s archives, is the Pen Park Hole in Southmead.

A letter of 21 August 1669, sent by Thomas Henshaw FRS to Sir Robert Paston FRS, states that the hole was discovered whilst quarrying for stone, and that the discovery was reported to King Charles II. In an account in Robert Hooke’s Lectures de Potentia Restitutiva, Captain Samuel Sturmy (1633-1669) states that the King commanded him to explore the hole, a sign of the royal interest in the potential financial benefit of a new mine as well as his passion for ‘novelty and prodigy’.

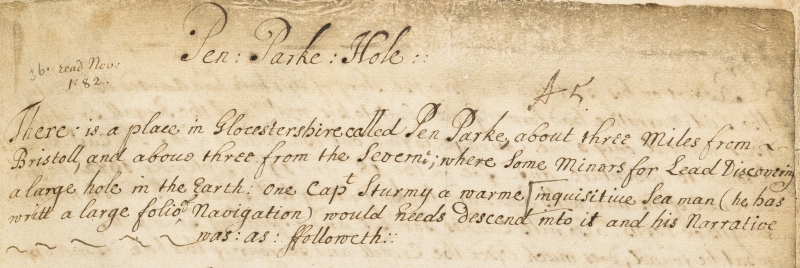

A document in our Classified Papers series (introduction shown above) contains a description of the hole and a version of Captain Sturmy’s account of his exploration. It states that Sturmy, an ‘inquisitive Sea man’, descended into the hole in July 1669, accompanied by a former miner. Sturmy’s account describes the cave as having an ‘aboundance of strange places, the flooring being a kind of a white stone, enameled with lead core, and the pendent rocks were lazed with salt-peter which distilled upon them from above and time had petrified’ as well as containing ‘a river or great water, which I found to be twenty fathoms broad, and eight fathoms deep’.

During the exploration of the cave, the former miner used a ladder to investigate a ‘great hallowing in a rock some thirty foot above us’. While he did apparently find the ‘rich mine’ he sought, he was also sent into a panic by the ‘sight of an evil Spirit’ and after this refused to go back. The cave experience continued to haunt Sturmy after they ascended. Four days later he was struck by ‘an unusual and violent headach’ which he attributed to being in the hole. Sturmy later developed a fever and passed away before the end of the year. This, along with the report of the spirit, was enough to keep any more explorers from descending into the hole until 1682.

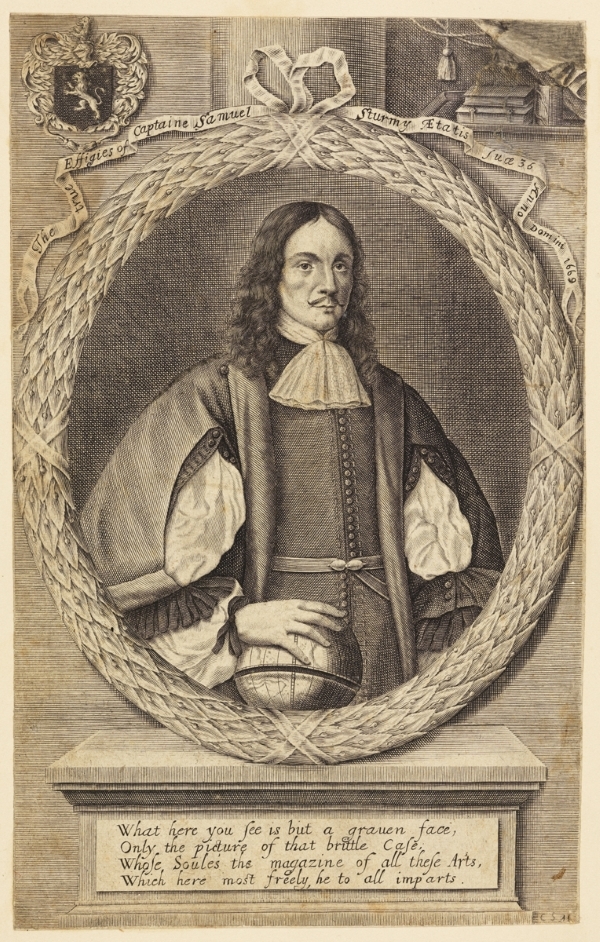

Captain Samuel Sturmy, from the frontispiece of The Mariner's Magazine (1669). Royal Society Newtoniana collection (MS/648), volume 2, page 157

Sturmy was not a Fellow of the Royal Society, but shows up in our collections in correspondence with Henry Oldenburg on topics including observations of the tides. He settled in Bristol where, in 1669 and prior to his ill-fated descent into Pen Park Hole, he published The Mariner’s Magazine, or Sturmy’s Mathematical and Practical Arts.

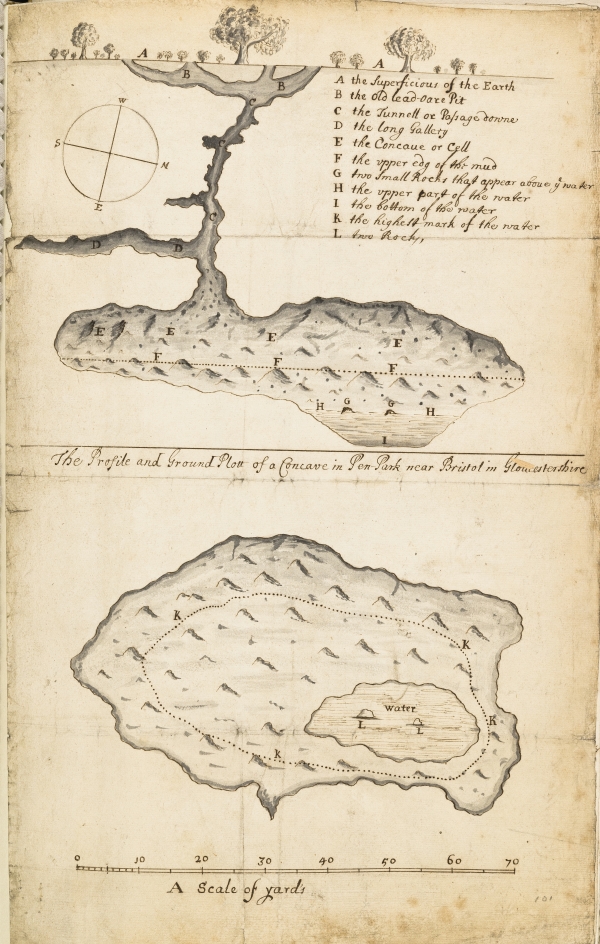

According to the document in our collections, which was also published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, one Captain Collins was surveying the English coast in 1682 and came into the River Severn. He visited Sir Robert Southwell (future President of the Royal Society), who told Collins the story of the hole and how it ‘had amused the country’, saying that there ‘wanted only some courage, to find out the bottome of itt.’ On 18 and 19 September 1682, Collins descended into the hole with a team of his men. Measurements were taken, and the trip passed without incident: ‘the Candles and Torches burnt clear soe as to discover the whole extent … nor was the Ayre any thing offensive.’ In terms of things moving around (spirits or otherwise), there was ‘nothing else in itt except a few Batts.’

Plan of Pen Park Hole by Captain Collins, 1682 (CLP/9i/36)

Despite this, the legend of Pen Park Hole lived on. In 1775, the Reverend Thomas Newnam visited the hole and, trying to measure the depth of it, unfortunately ‘fell into this dreary Cavern.’ An account by G S Catcott (available online and in our printed book collection) states that there were various attempts to retrieve the body in the following weeks, but it was not until 39 days later, when another man descended into the hole to fulfil a bet, that Newnam’s body was recovered.

Then, in 1876, a poem entitled ‘The Goblin’s Curse’ was published in the Bristol Mercury and Daily Post. You can read the full version online, though be warned that it goes on a bit; here’s the first verse:

Now find me the man with pluck so high

Who dares the Goblin's Curse Defy!

Now find him, I pray, in Bristol town,

Who that grim Hole dares venture down—

But when you have found him, bid him beware

Of all the dangers lurking there;

For horrible sights shall meet his view

If half that rumour says be true—

Knackers and gnomes and frightful shapes,

From which no trespasser ever escapes,

And goblins grim

Shall worry him,

And torture him out of a ghostly whim!

So find, if you can, that reckless soul

Who fears not the Goblin of Pen-park Hole!

The hole was closed in 1961 by Bristol City Council, but was reopened to accommodate landscaping in 1992 which allowed for it to be studied. These days, the hole is closed to the general public and is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) due to its populations of Niphargus kochianus, a rare shrimp species. The infamous goblin was never captured, and is assumed to remain at large.