A new musical theatre production tells the story of Royal Society Fellow Robert Hooke and his clash with Isaac Newton.

I’ve always had a love of science and a similar enthusiasm for musical theatre. It seems inevitable, therefore, that the two would fuse together eventually.

Back in January, I was offered the chance by a theatrical producer to write a musical about Robert Hooke and his clash with Isaac Newton. A few minutes of surface research shattered everything I knew of that falling apple story. The period had huge scientific ideas, rival egos and historical scandal... I was, quite literally, Hooked.

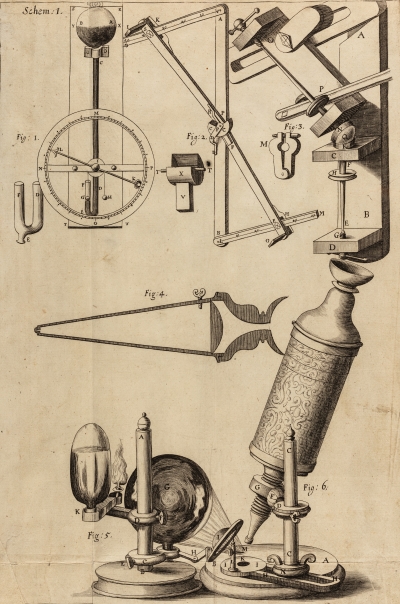

Microscope and other instruments from Hooke's Micrographia (1665)

Between several books, documentaries, archived lectures, online papers and a visit to the Royal Society Library to make notes from the published version of Hooke’s journal and his famous Micrographia, I built up a research bible of nearly 100 pages to work from. That was the easy part.

Musicals are typically between two and two-and-a-half hours long, so I somehow had to condense Hooke’s incredible, turbulent life into that timeframe. From Oxford University to Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society (making a name for himself by constructing the first successful air pump in England as assistant to Robert Boyle), and from City Surveyor after the Great Fire to clashes with Newton, there was a lot to pack in. I wrote down the chronology of his life on cards and marked the ones that seemed most important or held the best dramatic value. From this, I could also work out my cast of characters, many of whom kept recurring over time and had a major impact on Hooke’s life.

One challenge I came across was striking the balance of being informative and educational while also being entertaining and commercial. Luckily, Hooke’s complicated relationships with his brother and with his young niece, Grace, formed a strong counterpoint to his scientific work.

The biggest challenge of all, though, was Hooke himself. With no existing portrait and only a few accounts from his contemporaries, it was hard to place him in my head. To be the lead character of a musical, set against such iconic figures like Newton, Wren, Halley and Boyle, he had to be larger than life. Reading over his correspondence, the voice that came through was undoubtedly that of a genius... but so cocky! I played on that and made him almost childlike in his petty one-upmanship and sense of humour. When I had a treatment written, I sent it to various academics who all gave their thoughts before I started writing the show.

Musically I wanted something contemporary, both to engage a modern audience and also to reflect that Hooke and his peers were all, in a sense, ahead of their time. I therefore opted for a Math Rock feel (a subgenre of Rock typified by odd time signatures and dissonant chords) which seemed to mirror their complex, dizzying scientific thoughts.

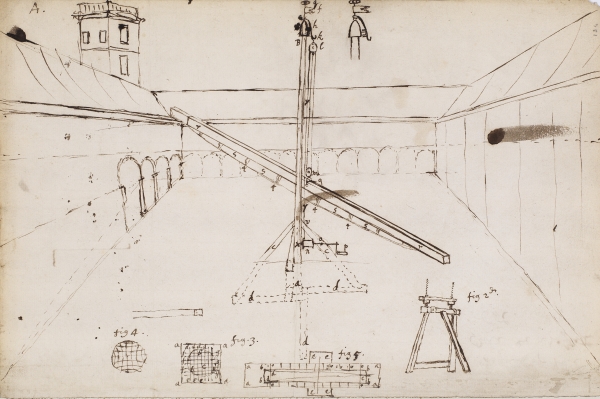

Telescope at Gresham College, by Robert Hooke, 1664 (CLP/20/61)

You can’t write a musical about Hooke without Newton, and I wanted to strike a balance and present both sides of the story. Because Newton is an outcast for much of the show, disengaged from the wider scientific community, I opted for a more classical, string-based sound to characterise him. When he does begin engaging with Hooke, however, Newton adopts Hooke’s melodic and lyrical motifs as well as his Math Rock sound, in order to reinforce a cross-fertilisation of ideas musically.

Many of my lyrics are taken verbatim from Hooke’s correspondence, including the letters he exchanged with Newton. I feature the 1672 dispute over light, where Hooke arrogantly dismisses Newton’s theory that light is made of particles, convinced it’s formed of waves (in fact both are correct). Then there are the 1679 missives about the inverse square law, where Hooke shares his theory that ‘the force on an object is a quarter as strong at twice the distance’, sparking Newton to prove the maths behind it – a task which evolved into the incomparable Principia Mathematica.

Design for an urn for the Monument to the Great Fire of London, by Robert Hooke, 1675 (MS/131/54)

As part of my research, I visited the Monument - designed by Hooke but always attributed to Wren - and watched everyone head up the tower to catch the cityscape view. Nobody stopped to look at the small plaque at ground level, dedicated to the man who built the foundations for the London we now have. From then on, I was determined to make sure his story gets told, and to put an end to a certain myth about an apple…

Take a listen on Spotify to the ‘Fallen’ concept album.