Louisiane Ferlier has co-edited a new volume on the history of books: 'Forms, Formats and the Circulation of Knowledge: British Printscape’s Innovations, 1688-1832'.

As the Royal Society Library remains closed to the public due to the Covid-19 pandemic, we find ourselves even more acutely aware of how much our jobs within the archive and book collections rely on a deep connection with physical material. Our readers come to us with questions about the materiality of the manuscripts, illustrations and books: is there a watermark on this letter? What is the size of this original plate? How many pages are in the specific copy of that journal? Are there marginal annotations to that book?

These investigations have always been close to my heart as the Digital Resources Manager, because they hint at what digital tools can or cannot do in terms of giving access to a collection. Our readers’ interest also proves that the reading room will always remain essential as a physical place of learning and research, and their questions show the importance of the field of studies known as history of books – a subject at the centre of my academic interests.

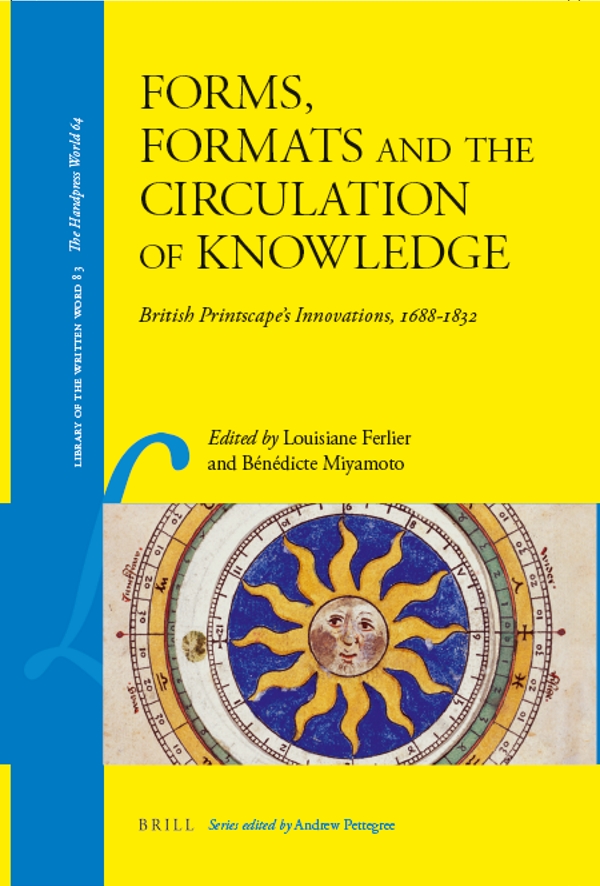

A few weeks ago, I was delighted to see the publication of a volume of book history I co-edited with Dr Bénédicte Miyamoto of the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3. The volume, Forms, Formats and the Circulation of Knowledge: British Printscape’s Innovations, 1688-1832, is a collection of eleven chapters by different contributors discussing various aspects of what we term the ‘printscape’ – the rich world of print produced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

We coined this term in reference to the ‘bookscape’ analysed by Professor James Raven, the influential book historian, who contributes a discussion of the importance of ‘jobbing’ (the printing of single sheet adverts, blank forms, affidavits and so on) to our volume. Knowledge and information didn’t only circulate in book form in the early modern era, and the Royal Society’s own paper collections are the symbol of how varied the early modern printscape could be.

To satisfy the thirst for knowledge of the period, printers, publishers and instrument-makers collaborated with explorers and scientists to make maps, globes, paper instruments (like the 1474 volvelle on the cover of the volume), journal articles and single-page leaflets as well as books. The variety of forms in which scientific knowledge could be printed depended on a fluid network of publishers, printers, copyright-holders, readers and authors, and was shaped by the inventiveness with which they coped with the notions of copyright and intellectual property.

Scientific content for the Illustrated London Almanack, edited by James Glaisher

Our edited volume resulted from two conferences, the first held in Oxford and the second in Paris, and is resolutely transdisciplinary. It investigates how print circulated information in a multitude of sizes and media, through an evolving framework of transactions. The authority of print is demonstrated by studies of prospectuses, blank forms, periodicals, pamphlets, globes, games and ephemera, gathered in eleven essays which engage with legal, economic, literary and historical methodologies.

The book is published in both print and digital formats, and is the fruit of many hours of research in libraries and archives across the globe as well as in-person discussions – all factors which embody powerfully the many media in which knowledge still circulates today. Ironically for a book which focuses closely on physical material formats, we will first have to launch it digitally in a virtual seminar organised by the Sorbonne Nouvelle and scheduled later today. While our opening conference in Oxford integrated the physical collections of the Bodleian Library, Oriel College and Jesus College as support for the discussions, in a Covid-19 world we find ourselves cut off from the material objects. I do hope that someday soon we can bring the discussion of forms and formats into the Library reading room of the Royal Society, and see how our hypotheses on the circulation of knowledge stand up to the messy yet beautiful reality of the Society’s early modern collections.

In the meantime, please take this as an invitation to continue to question what really lies behind the digital reconstructions I share with you regularly on this blog. Discover how your favourite childhood pop-up book was constructed, why a globe was originally a paper production, and who really made the encyclopaedia on the shelves of your own library. There is still a whole world of print to discover from the confines of our homes.