Ellen Embleton gets in the seasonal mood and explores Michael Faraday's famous Royal Institution Christmas Lecture, 'The Chemical History of a Candle'.

While 2020 has been a year unlike any other, the arrival of December’s cold weather has seen me fall into all-too-familiar patterns of overindulgence. To call my increased intake of chocolate an annual tradition might be a bit of a stretch. But it did get me thinking about how scientists from centuries gone by typically marked this time of year, and I was reminded of a renowned tradition in the scientific world: the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures.

The Royal Institution (RI) was founded at a meeting in the house of Royal Society President Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820), with the idea that it would promote science to a broader audience than existing learned societies. It did so primarily by means of lectures, and quickly achieved a reputation for providing excellent (if sometimes slightly dangerous) talks. The Christmas series evolved out of this, their defining qualities being the time of year in which they took place and the fact that they targeted a juvenile audience.

Satirical depiction of an RI lecture, showing Thomas Garnett (1766–1802) administering laughing gas to a colleague, ©The Royal Society

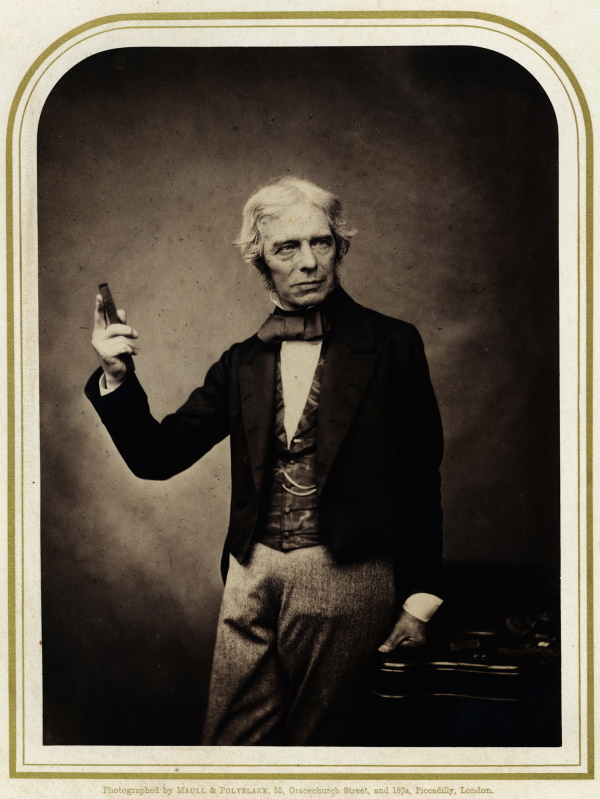

Many past and present Fellows of the Royal Society have been heavily involved with the RI, and many have delivered its Christmas Lecture since the first in 1825. However, none have done so quite as famously or frequently as Michael Faraday (1791-1867). Perhaps best remembered for revolutionising our understanding of electrical phenomena, Faraday was also a superb lecturer, with William Crookes FRS (1832–1919) describing him as ‘a sparkling stream of eloquence and experimental illustration’. He dominated the Christmas Lectures during the 1850s, giving one particular series three times: The Chemical History of a Candle.

Portrait of Michael Faraday by Maull & Polyblank, 1857, ©The Royal Society

Whether you’re celebrating Christmas, Hanukkah or Kwanzaa this winter, it’s likely that a candle will feature at some point. It’s an object that would have been even more familiar to audiences in the 1850s, and it was precisely this familiarity that Faraday was relying on in his lecture. He wanted to start with an everyday object, and from there take accessible steps towards more complex, scientific ideas. He believed the candle to be the perfect vehicle, or, put rather more eloquently by Faraday himself:

‘There is no more open door by which you can enter into the study of science than by considering the physical phenomena of a candle.’

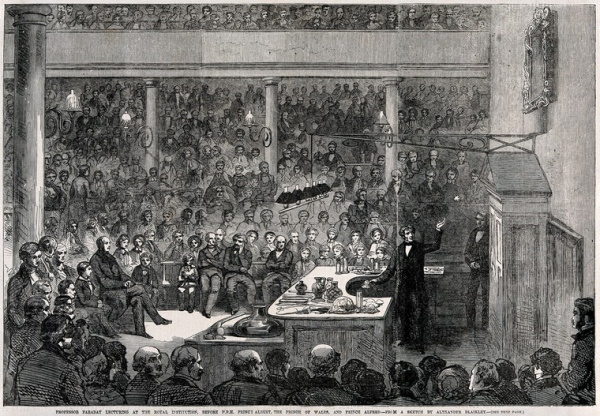

Michael Faraday presenting in the RI’s lecture theatre, 1856, Wellcome Library no. 40199i (CC BY 4.0)

Through the burning of a candle, Faraday introduced his audience to the concepts of mass, density, heat conduction, capillary action and convection currents. He spoke on the difference between chemical and physical processes, including melting, vaporisation, incandescence and combustion, and used a common parlour game (again, slightly dangerous!) called snap-dragon to illustrate the last of these points.

He investigated the nature of various gases, especially oxygen and carbon dioxide, drawing an analogy between the chemical behaviour of a candle and the basics of human respiration. A candle takes oxygen from the air, combines it with the carbon in the candle wax, and these form carbon dioxide and water. Humans, Faraday went on, produce the same reaction when they breathe: oxygen inhaled with air combines with carbon-containing food to produce carbon dioxide and water, which are then exhaled.

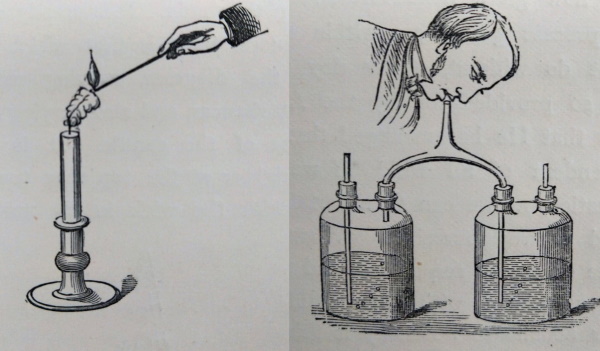

Figures from the printed work, illustrating (left) the conical shape of the flame, caused by rising convection currents, and (right) the effect of carbon dioxide (from the breath) on lime water ©The Royal Society

The popularity of Faraday’s candle lectures led to their being printed, first in weekly instalments in the Chemical News, and later as a book in 1861. The book has been continuously in print in English ever since – we have a rather lovely 1873 edition in our printed works collection – and Professor Frank James of the RI makes a case for it being the most popular science book ever published. If it doesn’t sound like your ideal winter reading, not to worry, we won’t hold it against you. But if you do settle down to another book or maybe a film by candlelight over the holidays, let Faraday’s concluding wish be in your thoughts:

‘Indeed, all I can say to you … is to express a wish that you may … be fit to compare to a candle: that you may, like it, shine as lights to those about you’.

Season's Greetings from all at the Royal Society Library.