Jon Bushell admires the ornithological work of two early Royal Society Fellows, Francis Willughby and John Ray.

British readers may be aware that this weekend is the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds’ annual Big Garden Birdwatch.

Since its inception in 1979, the survey has become one of the largest citizen science projects in the UK, with more than half a million households taking part last year. The data has been particularly valuable for ornithologists and conservationists – for example, sightings of house sparrows have dropped by more than 50% since the survey began, which has led to targeted conservation projects aimed at reversing this decline.

Amateur birdwatching was a popular pastime for wealthy individuals in Victorian Britain, but scientific ornithology traces its origins back much further. The sixteenth century saw the publication of a great number of books on natural history, including William Turner’s Avium Praecipuarum in 1544, the first printed book dedicated entirely to ornithology. But it was the work of two Fellows of the Royal Society that really transformed the study of birds into a discipline. Those Fellows were Francis Willughby and John Ray.

The spur-winged goose, found in wetlands throughout sub-Saharan Africa, from Willughby’s Ornithology

Willughby and Ray met at Trinity College Cambridge in the 1650s. Willughby was born to a wealthy family in Warwickshire and became a student at the college. Upon completion of his MA in 1660, he went on to be elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1663 at the age of 27. Ray, the older of the two, was a blacksmith’s son from Essex who had studied at Trinity in the 1640s, before becoming a college Fellow and collaborating with Willughby on several chemistry experiments. Their scientific interests were particularly complementary: Ray’s were primarily in botany, while Willughby’s focus was on animals. By the early 1660s, the pair had resolved to create an exhaustive catalogue of known flora and fauna across the world.

Where their work diverged from similar undertakings by earlier scholars was their classification system. Historically, many works had grouped animal and botanical species together based on similarities of appearance and anecdotal observations. Willughby and Ray wanted to make detailed anatomical observations to identify distinct and related species more effectively. To this end, they travelled across Britain and Europe in the 1660s, amassing a vast collection of specimens to support their work. Unfortunately, their partnership came to a premature end in 1672 when Francis Willughby died at the age of just 36.

Willughby’s death left Ray with several unfinished manuscripts on birds, fish and insects, in addition to his own writings on botany. Working from the extensive notes his younger colleague left behind, Ray began the task of publication with their bird research, which he published in 1676 in Latin as Ornithologiae libri tres; an English version, The ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton, followed in 1678.

Engraving of an osprey from Willughby’s Ornithology

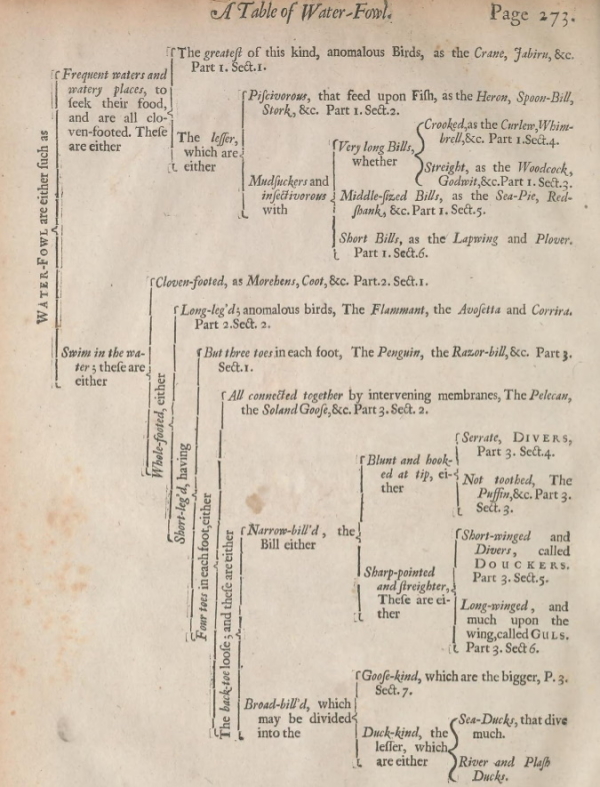

The book identifies several hundred birds studied by Willughby and Ray, with additional observations from several of their scientific associates. Via careful field and anatomical study, Willughby analysed shared characteristics in order to separate different species. Features such as the shape of the beak or the structure of the skeleton, and unique characteristics like markings on wings, were used to distinguish similar birds more clearly from one another. Willughby’s meticulous work certainly paid off: Ornithology predates Linnaeus’s work on binomial nomenclature, but the book still identifies and describes more than 300 unique bird species.

Table showing the classification of the various species of waterfowl, from Willughby’s Ornithology (Source: https://archive.org/details/ornithologyFran00Will/)

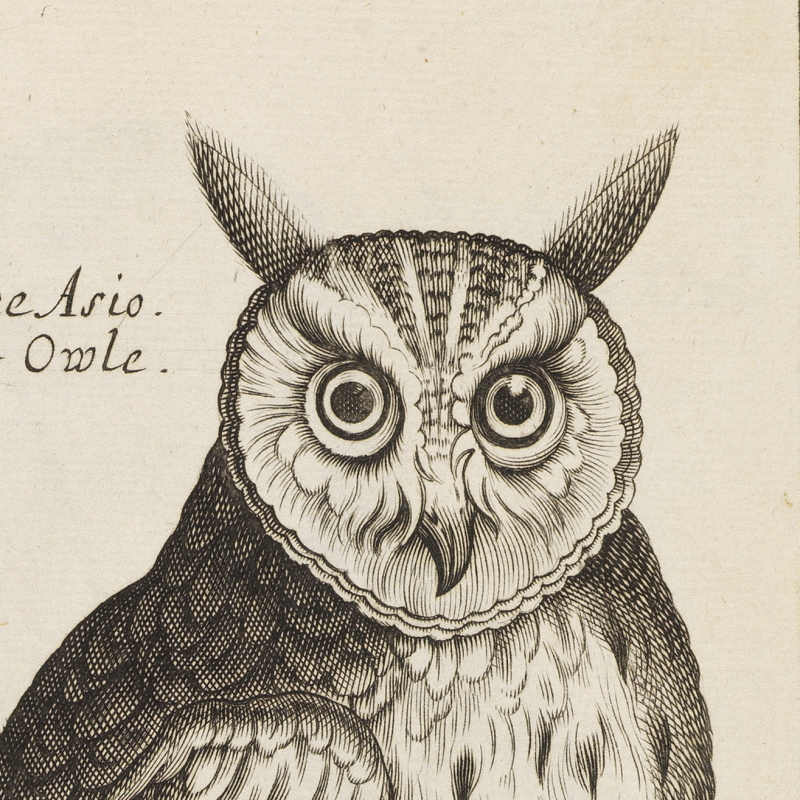

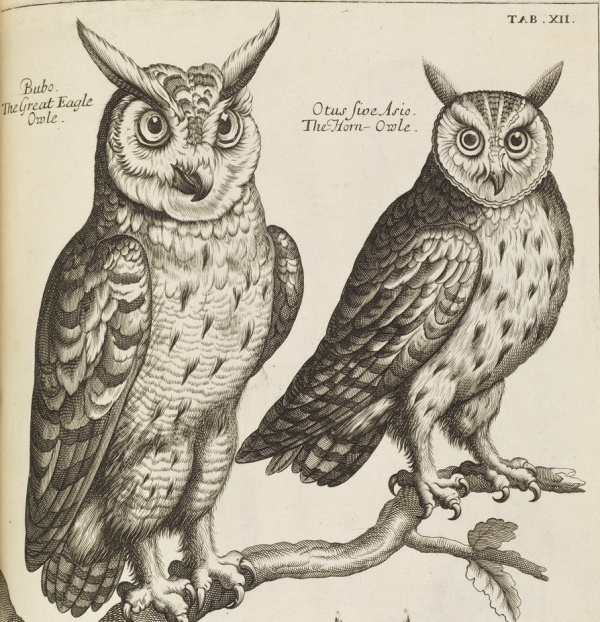

The book is notable for the 78 black-and-white engraved plates illustrating species described in the text, very few of which seem to have been drawn explicitly for Ornithology. During his travels, Willughby made a habit of acquiring collections of colour illustrations of birds, and commissioning artists to draw certain specimens. Following Willughby’s death, Ray used this collection, along with a number of other sources already in print, to select the most lifelike depictions to be engraved for the book. Ray generally communicated with the engravers by letter and complained that they often misunderstood or ignored his instructions.

The number of engravings had implications for the cost of commissioning and printing the book itself, and savings had to be made. Certain species described in the book do not have an accompanying illustration, usually in cases where they are too similar in appearance to another bird, or where the engravers failed to meet Ray’s exacting standards. The most obvious omission is female birds: in the preface to Ornithology Ray notes that they had ‘for the most part contented our selves with the figure of one Sex only, and that the Male’. Despite these limitations the book contains an amazing range of illustrations, and in the end Ray was pleased that the plates were ‘the best and truest, that is, most like the live Birds, of any hitherto engraven in Brass’.

Engraving of a wren from Willughby’s Ornithology

It’s hardly surprising that Ray had to give careful thought to the costs associated with the book. Anyone familiar with the early history of the Royal Society will know of Willughby’s follow-up work, De historia piscium (‘Of the history of fish’), also edited by Ray and published in 1686. With more than twice as many illustrations as Ornithology, the book was exceedingly expensive to print, and despite many of the fishy plates being sponsored by wealthy Fellows, the publication still almost bankrupted the Society.

Ray’s own scientific pursuits were no less impressive than Willughby’s and he published on the classification of plant species throughout his life. One portion of Willughby’s unfinished work eluded Ray, however: when he died in 1705 he had not yet completed the insects, possibly due in part to the publication challenges of De historia piscium. Nevertheless, Historia insectorum was eventually published by the Royal Society in 1710, although not as well-illustrated as the previous two works had been.

Engraving of two owls from Willughby’s Ornithology

Since their deaths, arguments have gone back and forth as to whether Willughby or Ray was the greater contributor to their scientific body of work. I don’t believe either man ever felt he was in competition with the other, and Ray certainly didn’t intend to claim credit for any of Willughby’s research after his death. Rather, he wished to celebrate the friend and colleague who had died before his time. The partnership of Willughby and Ray is quite simply that of two men who made fine co-workers. Birds of a feather flock together, after all.