Ellen Embleton admires the watercolours of Royal Society portraits created by copyist George Perfect Harding, and now housed in the Library's Newtoniana volumes.

The popularity of antiquarianism in the early modern period led to a general public interest in portraits of historical figures. The traditional forms of portraiture, such as oil on canvas and sculpture bust, were not accessible to most of the population, and they, quite understandably, wanted to see versions for themselves.

Thankfully, this was made possible via the technology of the time, namely, reproductive engravings and miniature copies of portraits. Often, these would be hung in print-shop windows, so even if you couldn’t buy one, you might know how a celebrated society figure appeared. The demand for portable portraiture is visible in the collections of the Royal Society, where we have a large number of engravings created between the 1600 and 1800s, as well as some lovely miniatures, and a great example of the resulting phenomenon of extra-illustrated works.

One man who was perfectly placed to capitalise on this trend was the miniaturist and copyist George Perfect Harding (1779-1853).

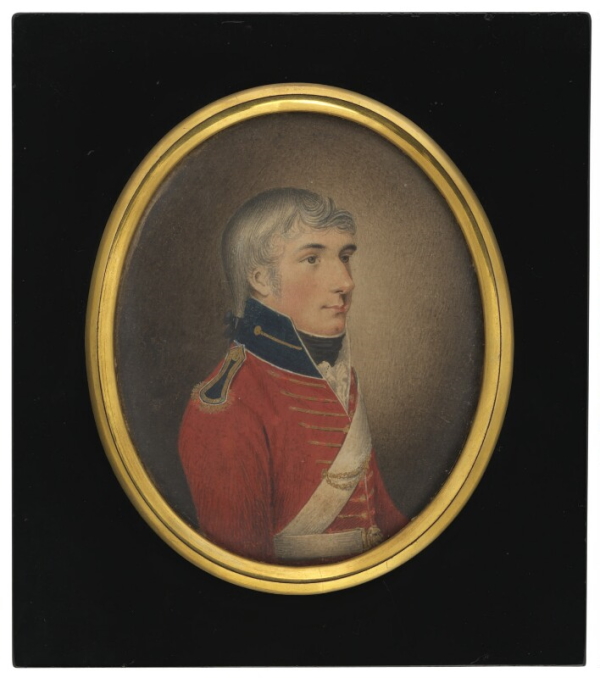

George Perfect Harding self-portrait, 1804, watercolour on off-white card © National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

George was the eldest son of another miniature painter, Silvester Harding (1745-1809), and was probably taught by his father, who enjoyed a successful career as a painter and engraver. George’s focus, by contrast, was on creating watercolour copies of historical paintings. For some forty years, George travelled Britain copying portraits and recording details of their history. In this pursuit, he visited many of the principle mansions of the nobility, as well as public galleries and universities.

His aim was always a small, portable facsimile of the original portrait, and a faithful one (perhaps not surprising, from somebody’s whose middle name was ‘Perfect’). Indeed, the author of an obituary for George published in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1854, bemoaned the fact that too many engraved portraits were only partial copies of their originals, with details of clothing and accessories omitted to save time and money, and praised George’s watercolours for directly differing in this respect.

Perhaps it was his reputation as an accurate and talented copyist that led to George being commissioned in the 1830s by Charles Turnor (1768-1853) to copy several of the Royal Society’s portraits for his Newtoniana collection (MS/648) – six large folios containing Isaac Newton memorabilia. This is where I encountered George’s work for the first time, as I made my way through digital surrogates from our Newtoniana volumes, cataloguing them for the Picture Library.

What struck me was the difference in colour palette between our original portraits and George’s copies. Consider the examples below from our collection:

Left, William Brouncker by Peter Lely c.1674, oil on canvas, and right, William Brouncker by George Perfect Harding, after Lely c.1838, watercolour on card. ©The Royal Society

Left, Isaac Newton by Charles Jervas, 1717, oil on canvas, and right, Isaac Newton by George Perfect Harding, after Jervas c.1838, watercolour on card. ©The Royal Society

Left, Johann Christoph Sturm by Heyman Dullaert, oil on canvas, and right, Johann Christoph Sturm by George Perfect Harding, after Dullaert c.1838, watercolour on card. ©The Royal Society

The robes in the watercolour copies of William Brouncker (1620-1684) and Isaac Newton (1642-1727) are strikingly vibrant, and captured in a way that surpasses our oil-on-canvas originals by Peter Lely (1618-1680) and Charles Jervas (1670-1739) respectively. Similarly, George’s copy of our Heyman Dullaert likeness of Johann Christoph Sturm (1635-1703) really illuminates the image, revealing certain details – Sturm’s blue eyes and rosy cheeks, and the tight curls of his wig – that are far less visible in the oil painting.

I was aware that George’s works are now scattered across a number of special collections in the UK and wondered whether anyone else had researched these nuances. On investigation, the answer turned out to be ‘yes’: in fact the National Portrait Gallery exhibited a number of George’s copies alongside their originals in 2016, with the explicit intention of highlighting this colour contrast. The exhibitors believed George’s copies to be a true representation of early modern paint pigments and hoped that they might give a sense of the appearance of the portrait before environmental factors and chemical changes took their toll.

This preservation of colour, the NPG suggested, was due to the very nature of George’s copies. As examples of portable portraiture, they would typically have been tucked away in folios and books, which protected them from external forces. This is certainly true of our George Perfect Harding originals, which were commissioned for privately-viewed volumes and, as a result, have been beautifully preserved.

Reassured that what I was seeing in George’s watercolour copies was a rare indication of a much earlier colour palette, I suddenly felt incredibly lucky to have the chance to work so closely with them, albeit in the form of digital surrogates. To get a sense of how these great portraits looked at the time of George's commission, when hanging in an earlier home of the Society, is a real treat, and once we have access to the collections again, I’ll be headed straight for the Newtoniana volumes for a closer look.