Frankie Chappell discovers how the production and economic importance of sugar made it a frequent topic of discussion in letters to the Royal Society.

When I was growing up, my grandmother always had a large stash of sweets and chocolates around her house. She would hand them out to anyone who came to the door, and was adamant that since she had had to go without during the War, she would ‘have what I like now, thank you very much.’

While sugar can be found across all types of food today, in the early years of the sugar trade it was an expensive commodity (at one time known as white gold) and its cultivation fuelled the transatlantic slave trade. Throughout the Royal Society’s history, there has been frequent scientific interest in agriculture and food, and sugar is a product that has linked farming, science, politics, engineering and key moments of historical change.

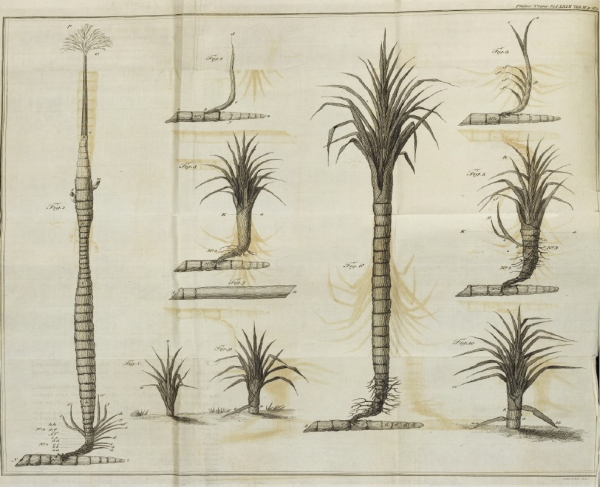

Plate from ‘Account of a new method of cultivating the sugar cane’ by Mr Cazaud, 1779 (https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1779.0019)

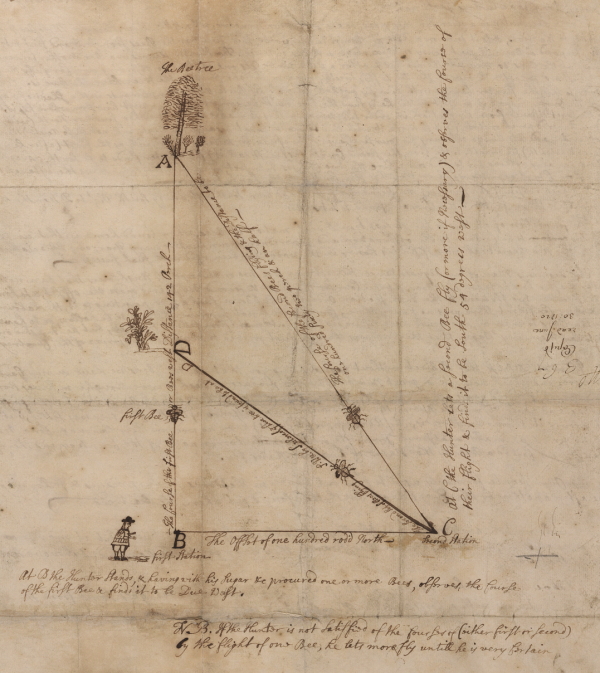

The popularity of sugar, its ties to world trade and the complexity of its production means it has been regularly discussed in scientific literature. Paul Dudley FRS (1675-1751) was the Attorney-General of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, New England, and submitted papers on natural history to the Royal Society. Demonstrating the sweet tooth of colonial settlers in North America, a number of these papers relate to producing sweeteners. In an article from 1720, he sets out how to successfully track down a beehive, through trapping and following the bees themselves, in order to obtain honey.

Plate from Paul Dudley’s 1720 paper, CLP/10iii/2

Another paper, published in the Philosophical Transactions in the same year, explains how sugar could be extracted from the maple tree. Dudley claims that ‘our Physicians look upon [maple sugar] not only to be as good for common use as the West India Sugar, but to exceed all other for its Medicinal Virtue.’ Methods of extracting the sap from the maple tree and producing sugar or syrup were actually developed by the indigenous peoples of north-eastern North America, and then passed on to and adapted by European settlers and colonisers.

A couple of years later, Dudley wrote again with a new way of making ‘molosses’ (molasses) from apples. New England formed one corner of the triangular trade, where sugar and molasses came from the Caribbean plantations, and were used to produce rum which was then transported to West Africa and traded for enslaved people. So it’s interesting that Dudley seemed occupied with finding substitutes for cane sugar. Giving us possible insight, Dudley states: ‘at Woodstock, in this Province, a Town remote from the Sea,’ where his acquaintance ‘discovered’ this method, the ‘West India Molosses is dear and scarce’.

The 'apple' letter was written 11 years prior to the passing of the Molasses Act (1733) by the British, which taxed the import of sugar and related products into the North American colonies from non-British foreign colonies, in order for the growers in the British West Indies to maintain a monopoly. As a result, the price of molasses in New England increased, but so did smuggling of sugar products into the colonies. In 1764 the Sugar Act was passed, with a lower tax rate but a firmer enforcement policy.

These acts and others like them formed the context for growing tensions which led to the American Revolutionary War. During this war, there was apparently an aversion to sugar and molasses from British-owned West Indian plantations, as part of the transatlantic slave trade, for patriotic reasons. Sugar products which could be made from locally-grown apples, for example, gained prominence. Alternatives to cane sugar were also popular during the early years of the American Republic, as a way to express opposition to the slave trade, and Marion Menzin argues that ‘New Englanders had always understood that their dietary choices were entwined with the destinies of faraway lands.’

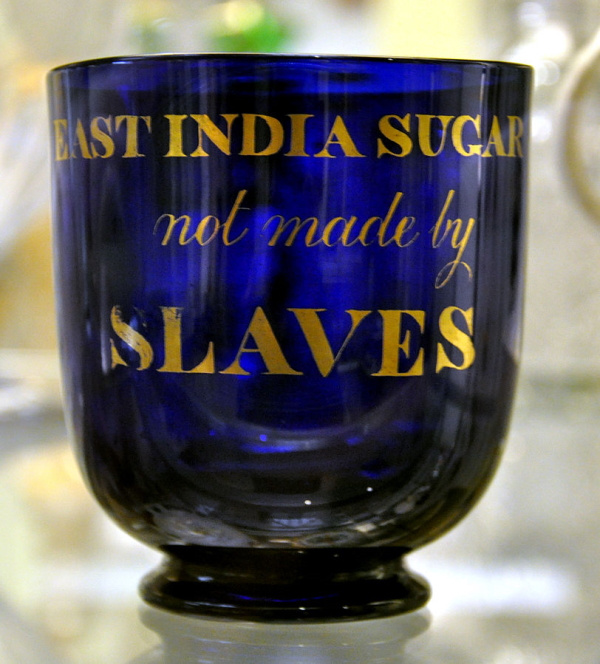

Blue glass sugar bowl ca.1820-1830, from Wikimedia Commons

Across the Atlantic, resistance to British West Indian sugar also came from British people themselves. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, Zachary Macaulay FRS (1768-1838) was so affected by his time on a sugar plantation in Jamaica that he joined the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade on his return to England. West Indian sugar was a central target of a boycotting campaign by British abolitionists, causing sugar sales to drop dramatically. The campaign has been compared to the Fair Trade movement of today, but its actual impact on the abolition of slavery is disputed.

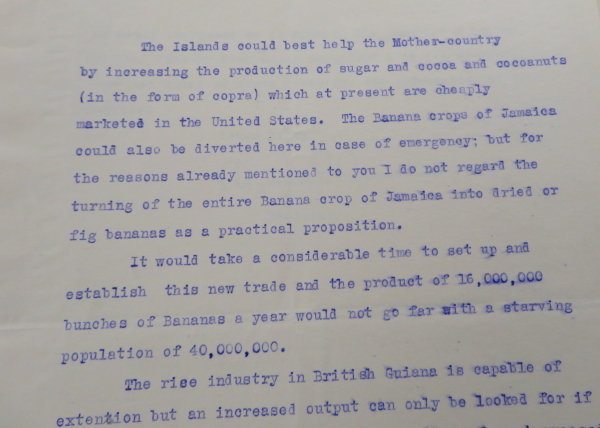

Slavery and ‘apprenticeship’ in the British Caribbean ended in 1838, followed by the introduction of indentured labour to the British West Indies, and sugar production continued in the region. By the time of the First World War, the economic landscape had changed. A document (shown below) in our Papers of the Food (War) Committee reports that ‘The [British West Indian] Islands could best help the Mother-country by increasing the production of sugar and cocoa and cocoanuts (in the form of copra) which at present are cheaply marketed in the United States.’ As we’ve seen in a previous blogpost, Britain continued to rely on its colonies for supplies, and by this time sugar had become a staple of the public diet.

MS/527/2/14/17 (detail)

MS/527/2/14/17 (detail)

In a far cry from its early medicinal image, sugar is now often the target of health warnings. As with many easily-purchasable goods, it is also not free from its ties to exploitation. Sugar historically represents a particularly strong example of how our diets are affected by international forces of politics and trade, but it’s far from the only one. Observing such forces led Thomas Sankara, late President of Burkina Faso, to proclaim, ‘Where is imperialism? Look at your plates when you eat.’