Frankie Chappell discovers some important conservation initiatives by Fellows of the Royal Society, featuring the saviour of the Père David’s deer and the author of a key early work on tree cultivation.

I’ll be candid, this started as a blog simply about squirrels. Spending so much time at home over the past year and a half, I’ve had time to appreciate the local wildlife. This has mainly consisted of a family of grey squirrels who have made themselves at home in my roof.

Eastern grey squirrel by Mark Catesby, 1731 (RS.18818)

Most people are aware by now of the grey squirrel’s reputation as an ‘invasive species’ and the alleged nemesis of the red squirrel. The greys have been targeted with culling, and scientists are considering putting them on birth control. But even now, when they’ve pushed their way into my eaves and terrorised my cat, I still have a soft spot for them. So I went hunting for mentions of grey squirrels – my colleague Rupert wrote on exotic specimens last year, so this continues the story closer to home.

As it turns out, if you’ve ever had the joy (or terror) of an interaction with one of the squirrely regulars in Regent’s Park, you may well have one of our own Fellows to thank. A study a few years back concluded that humans were much more to blame for the prevalence of grey squirrels in Britain than the squirrels themselves. According to the study by Dr Lisa Signorile, one Herbrand Russell FRS, the 11th Duke of Bedford, had a particularly large impact, releasing squirrels across the country, giving them to his friends and kicking off the ‘epidemic’ of greys in London by letting them loose in Regent’s Park. He may also have been responsible for introducing the black squirrel to Britain from the Americas.

Père David’s deer (RS.13086)

Squirrels weren’t Russell’s only passion, however. His love for all things zoological led to him becoming President of the Zoological Society of London between 1899 and 1936. From 1894 to 1903, the Duke brought 18 Père David’s deer, or milu, from Europe to his own Woburn Estate in Bedfordshire. The deer originated in China and were ‘discovered’ by French zoologist Père Armand David, when the sole remaining deer were part of the Chinese Emperor’s royal herd. David exported some to Europe, but during the First World War, the milu in Europe disappeared, meaning the herd at Woburn Estate were the only ones left. The conservation efforts of Russell have meant that the Woburn milu are now the largest herd in the UK, and in the 1980s, 40 deer were sent back to the People’s Republic of China, where the species is now thriving.

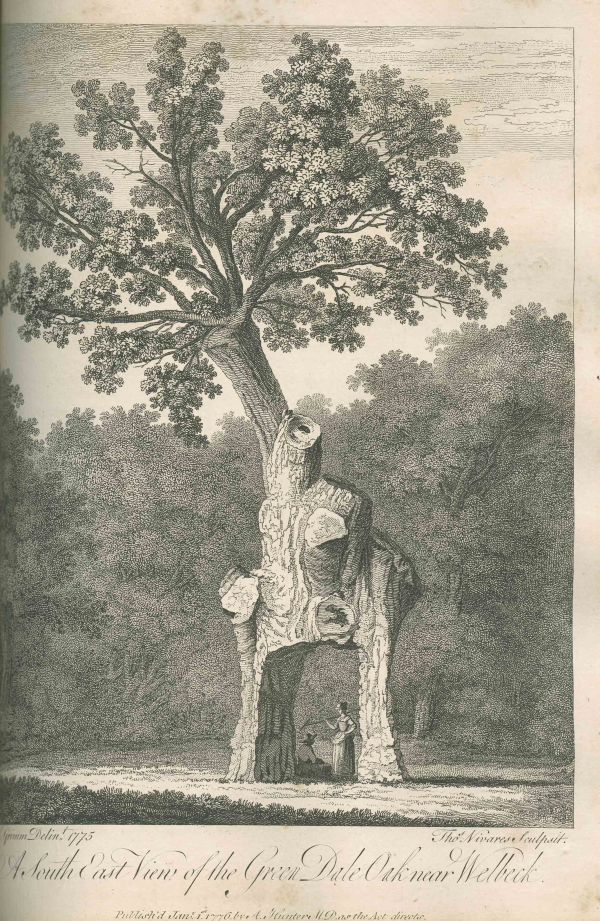

The ‘Green Dale Oak’ near Welbeck, from our 1786 edition of Sylva (RCN 22173)

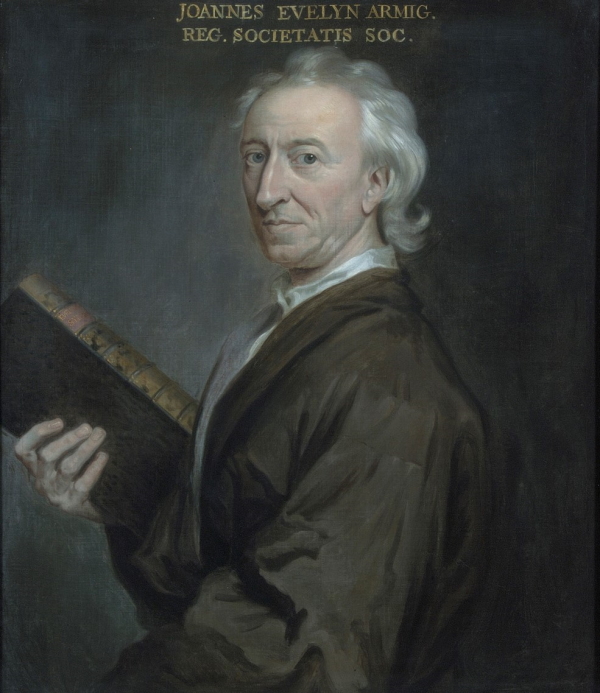

By this point, I was thoroughly distracted from my squirrel mission and drawn into the Royal Society’s links to the conservation movement. Russell was not the only conservationist in the Society’s ranks – in fact, some people say that the conservation movement itself can be traced back to the first book published by the Royal Society. Sylva, or A discourse of forest-trees, and the propagation of timber in His Majesties dominions by John Evelyn FRS, was published by the Society in 1664, having been presented as a paper two years earlier. In it, Evelyn, at the behest of the Society, highlighted deforestation in England and provided practical advice on tree cultivation and different species.

Although targeted at landowners, Sylva ended up being extremely popular with wider audiences and influential for centuries after its publication. Evelyn linked his encouragement to replenish trees with the reliance of the navy on timber for building ships. Consequently, a later edition of Sylva coincided with the decrease in timber after the Napoleonic Wars, and his influence can be seen in the establishment of the UK Forestry Commission after World War I. But a lot of the trees he painstakingly described were not appropriate for building ships – it seems Evelyn just loved a good tree!

John Evelyn by Sir Godfrey Kneller, ca. 1687 (RS.9268)

Three years earlier, Evelyn had published Fumifugium: or, The inconveniencie of the aer and smoak of London dissipated. Together with some remedies humbly proposed by J.E. Esq; to His Sacred Majestie, and to the Parliament now assembled, a snappily-titled pamphlet on air pollution. Evelyn was one of the first to write about the issue, and in Fumifugium he argued that poor air quality could harm human health, coal-burning industries should be moved out of London, and trees and plants should be grown in the capital to improve the quality of the air.

Despite centuries of separation, Evelyn and Russell remain tied to the modern day. Evelyn’s concerns seem very close to some of our own, while Russell’s actions have had a direct impact on the ecology of Britain. Ideas such as Evelyn’s remain resonant with environmentalists, despite recent studies linking nature conservationism with colonialism and neo-colonialism. The idea of invasive species has also been criticised, not least because of the role humans like Russell have had in ‘invasions’.

Unfortunately, no local grey squirrels were willing to speak to me on the record.