Clues to the early life and scientific interests of Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy can be found in his portrait at the Royal Society, as Daniel Belteki explains.

I recently started work at the Royal Society as the new Digitisation Project Coordinator. Visiting the Society’s home in Carlton House Terrace for the first time, I was blown away by the number of portraits hanging on the walls. They remind visitors that science has always been a human enterprise.

Since there’s limited space on the walls, selecting which portraits to display and which to keep in storage is a contentious issue. The responses shape how the history of science is remembered and how science as a practice is presented by the Society.

It’s also intriguing to see who gets depicted and how. There are multiple portraits and busts of famous figures like Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin. The differences between portraits of the same person offer insights into how public perceptions changed over time and how the sitter attempted to self-fashion their image.

One interesting tale surrounds the portrait of a figure maybe less well known to the general reader, the astronomer Sir George Biddell Airy (1801-1892). Airy is an odd character for historians of science. He is notorious to some as the dictatorial director of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, who (according to this Notes and Records article) spent days labelling boxes with the word ’empty’ to keep everything organised. He was the nineteenth-century manifestation of discipline, order and micromanagement. However, he was fondly remembered by his friends for playing music, writing satirical poems about other figures of science such as Charles Babbage, while tempting others into breaking their sobriety, and enlivening dinner parties by reciting comic poetry. Depending on whether one consults his letters exchanged with friends or foes, one gets a very different impression of him.

His connection to the Royal Society is similarly tumultuous. Although he communicated papers to the Society regularly during the 1820s, he refused the initial offer of a Fellowship in 1828. A few days after this offer, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, an organisation which was critical of the Royal Society’s administration of astronomical matters such as allowing errors to creep into the Nautical Almanac (the leading publication related to navigation at sea). Despite this, he was awarded the Royal Society’s Copley Medal in 1831 for his contributions to the field of optics.

In 1835 Airy was appointed Astronomer Royal, so that he became a scientific public servant. It was only after taking up this position that he became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1836. He served as a member of the Society’s Council many times, and was eventually elected President in 1871. He was hesitant to accept the position due to his other public and scientific engagements, which led to a relatively short-lived presidency lasting only two years.

The Royal Society portrait collection includes a large canvas of Airy. Its presence in the collection is somewhat unusual as the painting dates from the years 1833 and 1834, while Airy only became a Fellow of the Society in 1836. The object file of the painting reveals that it was not initially with the Royal Society. Instead, it used to hang on the walls of the Cambridge Observatory (today the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge). Whether the portrait was originally intended for the Observatory is not known for certain, but it is intentionally filled with iconography and symbols representing Airy’s connections to Cambridge and his achievements during his early career.

The portrait was painted by James Pardon who was at the time active as a portrait painter around Suffolk. Airy maintained deep personal ties to the region. He went to school in Bury St Edmunds, where he became known for his excellent memory and his ability to construct pea-shooting devices. He also fondly remembered the months spent with his uncle, Arthur Biddell, who lived in Playford, near Ipswich.

Biddell introduced Airy to scientific topics and to local persons of interest such as the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) and the agricultural engineer Robert Ransome (1753-1830). These connections had a great impact on the young boy. Later in his life, Airy designed and erected an obelisk in Playford commemorating Clarkson’s life. Moreover, Ransome was the person who showed Airy the planet Saturn through a telescope.

When Airy sat for the portrait, he was the Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge University. To represent this role, Airy is shown wearing a gown, jacket, waistcoat, white shirt and tie. Taking a quick glance at the photograph of the succeeding Plumian Professor, James Challis, we notice that he is wearing similar academic dress. Therefore, the purpose of the portrait was to present Airy as a university professor. Airy was well aware of Cambridge fashions. His autobiography notes how he wore the ‘outdated’ student uniforms (drab knee-breeches), which made him ‘in some measure distinguishable’. However, by the end of his first year as a Cambridge student, he conformed to the new fashion trends.

Although much of the background is obscured by drapery, on the left of the portrait the building of the Cambridge Observatory can be seen. It establishes Airy’s professional role as the director of the Observatory, where he promoted a new format for publishing astronomical observations, reducing the time and energy that astronomers spent on interpreting the published data. While at Cambridge, he re-examined the motions of Venus and Earth, and for the resulting paper he received the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society as well as the Lalande Prize of the French Academy of Sciences.

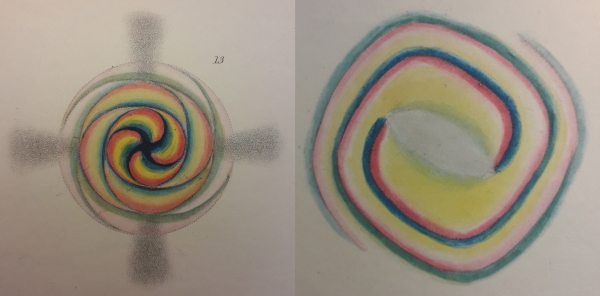

While the Observatory reflects the astronomical research of the Plumian professorship, the right-hand side of the portrait pays attention to experimental philosophy such as mechanics and optics. Airy’s placement in the middle of the portrait depicts him as the person combining these two different fields. The latter is represented on a desk, where there is an open notebook and some loose sheets of paper. On one of the sheets, colourful illustrations similar to these are visible:

The figures are from a paper by Airy on optics, published in the fourth volume of the Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society (1833). The paper examined the nature of the light forming the two rays produced by the double refraction of quartz. It combined Airy’s interests in various fields, such as mathematics, geology, optics and physics. The experiments were significant as they formed part of Airy’s larger work in optics for which he was later awarded the Copley Medal.

Reassembling the forgotten meanings of portraits will always remain a fun exercise. It helps us unearth new information about the lives of individuals, and reminds future generations about the sitter’s priorities at the time. Airy's portrait freezes him at a point when he was a rising figure within the scientific community, and the objects surrounding him in the portrait remind us of this time of his life.