Join Library Manager Rupert Baker on a virtual walking tour, visiting historic buildings near the Royal Society which were designed by our Fellows.

The Open House London festival takes place every September, and in previous years I’ve enjoyed showing visitors round the Royal Society’s home in Carlton House Terrace.

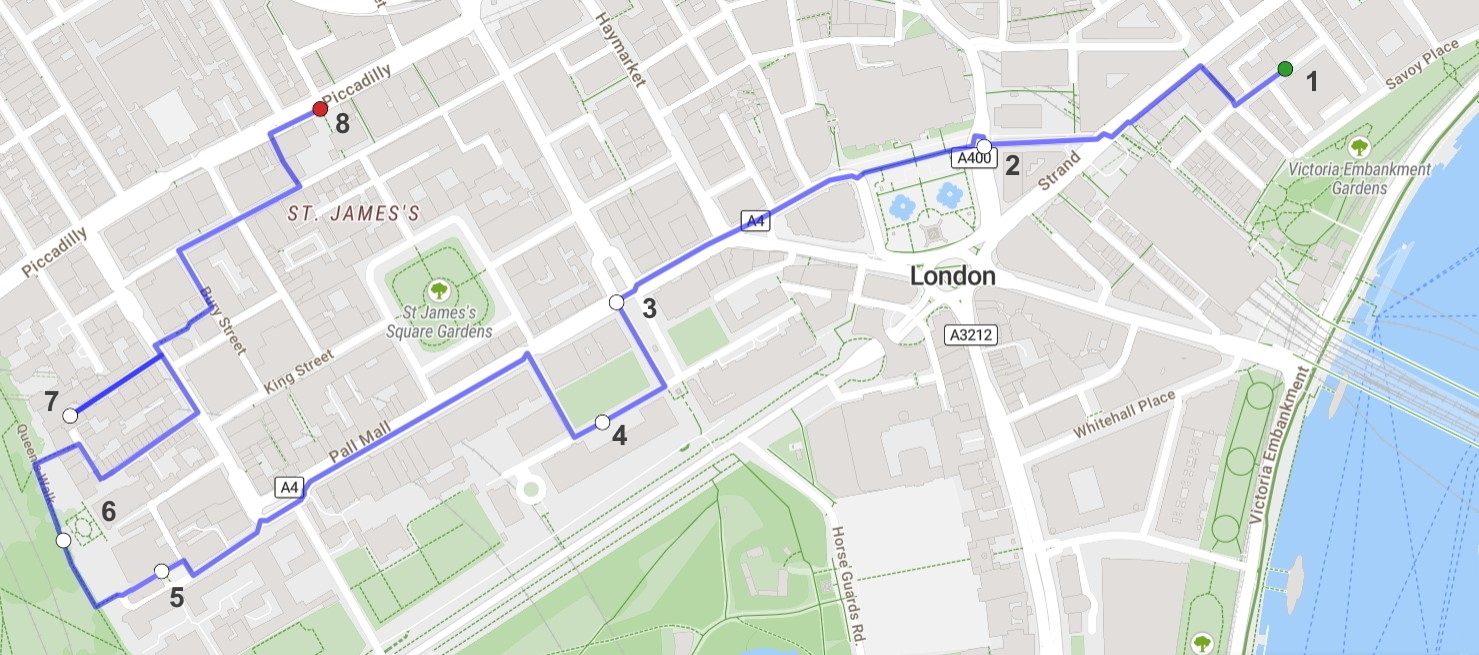

Circumstances mean that we can’t throw our doors open in September 2021, although you can still get a glimpse inside our building – and take a virtual tour – by visiting our Open House Online 2021 webpage. Meanwhile, to stave off my tour guide withdrawal symptoms, I thought I’d take a walk around the neighbourhood, virtual umbrella raised high, and map out an architectural route for you to follow:

(map created using onthegomap.com)

(map created using onthegomap.com)

There are eight stops on the tour, taking in a total of ten buildings. You can stroll them virtually, or walk the 1.7-mile route in an hour or so at a leisurely pace.

So what do the buildings on the tour have in common? The answer may surprise you: they were all designed by Fellows of the Royal Society. Architecture isn’t really one of the disciplines that gets you elected to our Fellowship these days (and since 1837, architects have had a distinguished ‘Royal’ body of their own, now usually referred to as RIBA), but there were several notable names in the first couple of centuries of our existence. See how many you recognise as you take the tour – and if I tell you that it ends at a seventeenth-century church, that should give you a major clue to the identity of our most famous ‘Fellow architect’.

Your starting point is in John Adam Street, just south of the Strand and number 1 on the map above. The street itself is named after a member of a noted Scottish architectural family, but it’s his younger brother Robert Adam FRS (1728-1792) who concerns us here. Elected to the Fellowship in 1761, the same year in which he became Architect of the King’s Works, Robert’s ideas had been strongly influenced by his exposure to classical architecture during a four-year ‘Grand Tour’ to the continent.

The area south of the Strand became the site of the Adam brothers’ great (though ill-fated) neoclassical block, the Adelphi Buildings, built between 1768 and 1772. At the same time, a comparatively new institution, the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, was looking to move into its own premises, and commissioned a house at number 8 John Adam Street:

(all building photos taken by the author)

This was designed by Robert and a third Adam brother, James; a plaque on the wall gives the precise dates of foundation and completion:

The Royal Society of Arts or RSA, as it’s now generally known (and yes, there is a steady flow of redirected enquiries between our library and theirs!) has been in the same building ever since. This represents a far longer period of stability than ‘our’ Royal Society – see the Gallery on our Open House Online 2021 webpage for further information on our many London homes over the centuries.

Crossing the Strand and heading to the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square, you’ll reach your second stop: the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, designed by another Scottish architect, James Gibbs FRS (1682-1754). Schooled in the Italian Baroque tradition during his own extended travels around Europe, Gibbs won a competition in 1720 to design a new church on the site, which already had ecclesiastical links going back to the medieval period:

Completed in 1726, St Martin’s – now a long way from any fields – is both a thriving community church and a familiar sight to tourists. It remains Gibbs’s most celebrated London work, and likely played a part in his election to the Fellowship in 1729. His best-known later commission is the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford.

A short walk across the top of Trafalgar Square and along Pall Mall to Waterloo Place leads to map location 3, a three-for-the-price-of-one view of the exclusive private members’ clubs of St James’s:

Starting on the right of the photo, the two north-facing buildings are the Reform Club and, sandwiched in the middle of the block, the smaller Travellers Club. Here’s a side-by-side view of their front elevations in morning shadow:

The Travellers (L) and Reform (R) clubhouses are both the creation of another of our architect Fellows, Sir Charles Barry FRS, albeit a while before his election to the Fellowship in 1849. His election certificate describes him as ‘Distinguished for his acquaintance with the science of Architecture’, and indeed he was: launched on a career by friends and aristocratic connections made on the obligatory Grand Tour, Barry rose to be a leading figure in the Italianate style first popularised in Britain by John Nash. The Travellers clubhouse (1832) is considered to be Barry’s first major work in this style, and the Reform (1841) one of the finest, influenced by the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. By this latter date, Barry also had another small project on the go, of course: the Houses of Parliament.

Returning to the photo-before-last, the east-facing frontage in full morning sunlight is that of the Athenaeum, whose Neoclassical clubhouse at 107 Pall Mall was designed by Decimus Burton FRS to occupy a plot of land made available after the demolition of Carlton House. It was completed in 1830, making it the earliest in this distinguished Pall Mall block. Decimus himself was something of an early starter: the tenth child (hence the name) of Regency property developer James Burton, he was only 26 when he began work on the Athenaeum, and was soon elected to our Fellowship at the age of 32, proposed by such luminaries as Michael Faraday, Marc Isambard Brunel and Charles Lyell.

A short walk across Waterloo Place to Carlton House Terrace takes you past the Royal Society’s front door (we’ll let you in for Open House 2022, fingers crossed!) to the fourth stop on the tour route. Here you can see numbers 3 and 4 Carlton House Terrace, now home to the Royal Academy of Engineering (above). The overall scheme for the Terrace – also built on the gardens of the old Carlton House – is generally attributed to Nash, assisted by Decimus Burton, but these two houses are exclusively Decimus’s work, commissioned by Lord de Clifford and Lord Stuart de Rothesay respectively.

The tour route now returns to Pall Mall, heads west past St James’s Palace, and follows Cleveland Row as it narrows to a small passage between railings into the eastern side of Green Park. Just before you reach this cut-through, at point 5 on the map, you’ll see an imposing portico on your right, with the inscription ‘Restituta Anno Domini MDCCCXLIX’ above the doorway:

This is Bridgewater House, another of the works of Sir Charles Barry FRS, who rebuilt the house in 1840-54. It’s now in private hands, so the front door will likely remain closed to you, though a local history society I’m acquainted with via Royal Society tours does seem to have managed a visit. And if you’ve watched more Downton Abbey than me (not difficult – a single episode will do), then the exterior might be familiar to you as the fictional Grantham House…

Once you’ve turned right into Green Park, you’ll see the best view of Bridgewater House when you look back east. Here it is (L), with my apologies for not leaving work a bit earlier, allowing the late summer afternoon shadows to creep up the front before I could take my snaps:

Carry on up the side of Green Park, towards the tube station, to glimpse another stunning mansion facade: Spencer House (R), number 6 on the map and open to tour groups on Sundays. While the facades of Spencer House were done by a non-Fellow, John Vardy, the interiors were the creation of his successor on the project from 1758, James ‘Athenian’ Stuart FRS.

Another eighteenth-century architect with Scottish origins, Stuart was from a much humbler background than his contemporaries – I doubt the Adam brothers had to walk to Italy on their Grand Tour, as Stuart is said to have done on his. Elected to the Royal Society in the same year as his Spencer House commission, Stuart’s election certificate notes that he ‘particularly applyed himself to the study of antiquity, during a long residence in Greece and Italy’, and his published work on his return to London helped to inaugurate the Greek Revival movement in Britain.

OK, we’re nearly there now, but the route briefly gets trickier: continue through Green Park and keep an eye out for a small alleyway to your right. This goes via a narrow covered passage – breathe in if anyone’s coming in the opposite direction – into St James’s Place, where the front door of Spencer House is situated. Walk on to St James’s Street, turn left and slightly uphill, then left again into Park Place, a short street which dead-ends at the gateway to the Royal Over-Seas League, tour stop number 7. Here it is, as viewed from Park Place (L) and Green Park (R):

The building – much older than the organisation it accommodates – consists of two houses, Rutland House and Vernon House. The former is another creation of James Gibbs FRS (St Martin-in-the-Fields, remember?), and you can read about it in this Open House blogpost I found on their website.

To conclude the tour, you’ll need to retrace your steps back along Park Place, and then zig-zag up to 197 Piccadilly. This is the eighth and final tour stop: St James’s Church, Piccadilly, consecrated in 1684:

The church was designed by Sir Christopher Wren FRS, Founder Fellow of the Royal Society, President 1680-82, and definitely the most famous architectural name on our roster. It was rebuilt following heavy damage in WWII; if you seek Wren’s original monuments elsewhere, of course, there are plenty of other churches to choose from, including a pretty impressive cathedral which you may know.

That’s outside the range of this tour, however, as are many other London buildings designed by Royal Society Fellows: the Royal Observatory, Sir John Soane's Museum, Somerset House and the Monument, to name but a few. I hope you’ve enjoyed my starter walk, anyway, and are feeling inspired to venture further in the footsteps of our ‘Fellow architects’.