Picture Curator Katherine Marshall takes a look at theories of colour, from Newton and Goethe to Chevreul and the Impressionists.

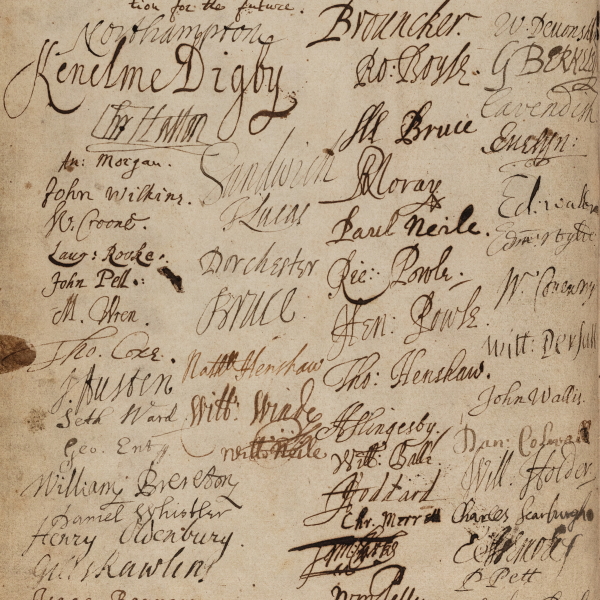

As we head into winter and the light fades, I’ve been turning to a little colour theory to brighten my day. The study of colour can be traced back to antiquity, but the science began with Isaac Newton FRS and the first colour circle.

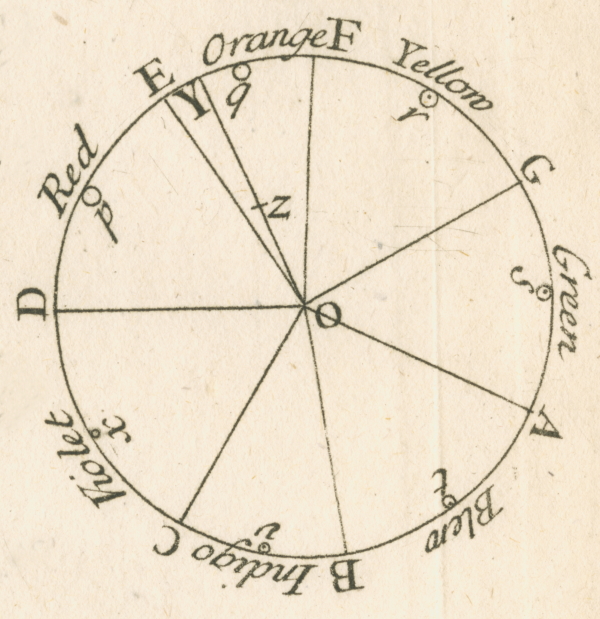

Newton published his ‘new theory about light and colors’ in the Philosophical Transactions in 1672, following his ‘crucial experiment’ in which he used a prism to split white light. Over 30 years passed until he published Opticks (1704), his treatise on light, which included the first colour wheel. Newton set the seven spectral colours into a circle of unequal segments, based on the pattern of musical scale, and created a geometric model which underpins all subsequent theory on colour harmony:

Colour wheel from Newton’s Opticks (2nd ed., 1718)

It was Brook Taylor FRS, mathematician and secretary to the Royal Society, who presented the benefits of Newton’s work in an appendix to his New principles of linear perspective (1719). Here, he suggested that Newton’s colour circle could be used as a guide for mixing paint, despite the theory being based on additive colours (from light) rather than pigment.

Printmaker Jakob Christoffel Le Blon effectively applied Newton’s optical theory to create a new printing technique. Using separate engraving plates for the three primaries, and overlaying the plates on to the same print, he creates the first full colour mezzotint, and it is this technique which still underpins the colour printing processes used today. An example of Le Blon’s printing method was presented to the Society in 1731 and is an illustration to a publication on gonorrhoea by William Cockburn FRS. The vivid rendering of the dissection of a penis certainly shows off the brilliance of his new printing system, and is presumably retained in the Society’s scrapbook of illustrations (MS/131) as an example of cutting-edge technology.

Préparation anatomique des parties de l'homme servant à la generation, J C Le Blon, 1721. RS.16441

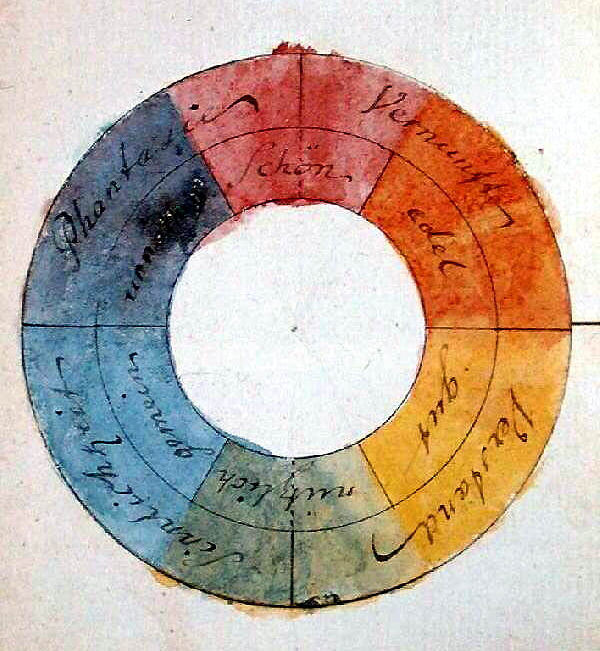

During the Romantic period in the early nineteenth century, the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe conducted his own researchers into spectral colour using the prism experiment. He came to the conclusion that colour appears where light and darkness meet, supporting the ancient philosophy that colour came out of black and white, in a direct argument against Newton’s work.

Farbenkreis zur Symbolisierung des menschlichen Geistes- und Seelenlebens (colour circle for the symbolization of the human mental and spiritual life), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1809. From the Frankfurt Goethe Museum. Wikimedia Commons

Although the science of Goethe’s model was later disputed, his approach to how colour is perceived and experienced made it an important study in its own right. His symmetrical colour wheel divided into six colours, three primary and three secondary, is accompanied by descriptive terms such as ‘schon’ (beautiful) and ‘Sinnlichkeit’ (sensuality), and his ideas on the connection to the human experience inspired artists. The British watercolourist J M W Turner paid tribute to Goethe with a pair of paintings which he created shortly after the English translation of the Theory of colours in 1840.

Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis, exhibited 1843. Joseph Mallord William Turner. Tate Archive CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

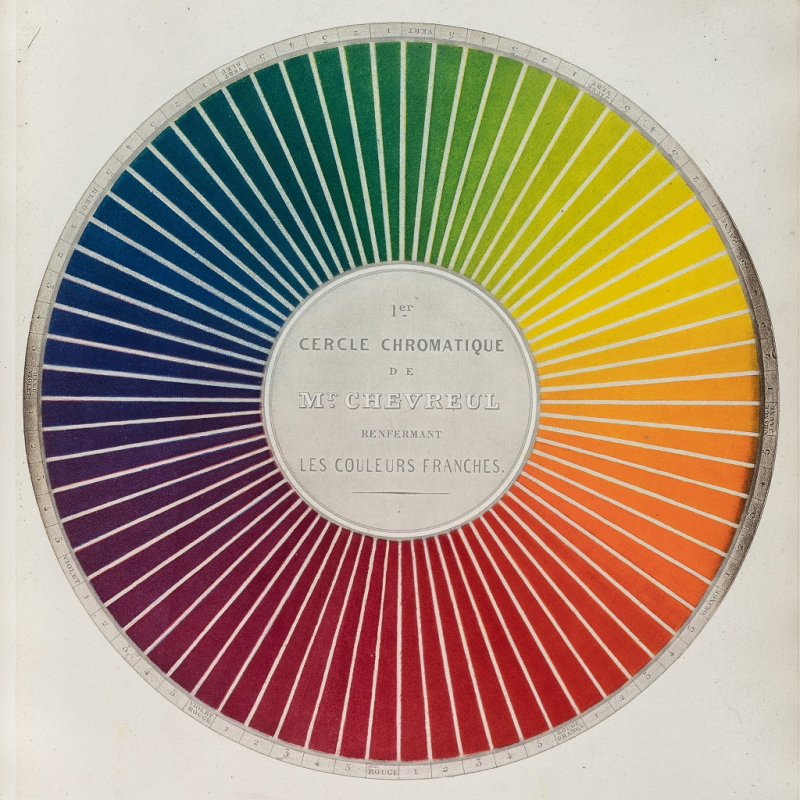

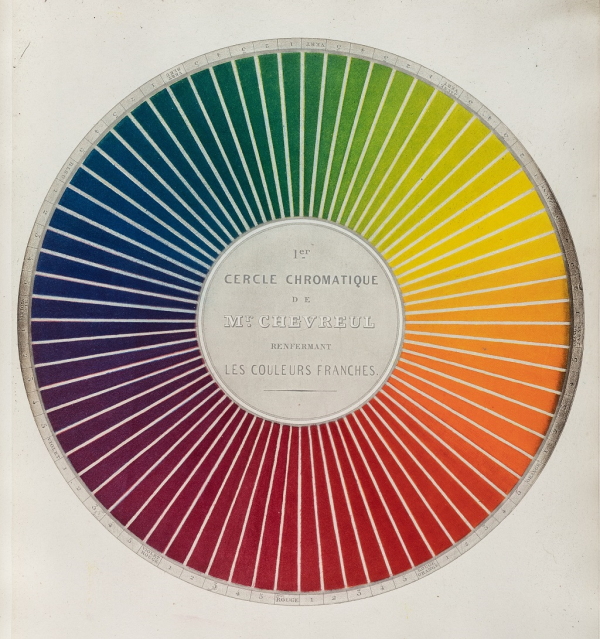

The principle of colour harmony was further developed by the French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul ForMemRS. In his role as director of dyeing at the Gobelin tapestry works in Paris, Chevreul established his theory of simultaneous contrast, or how the perception of one colour can be altered by its position next to one which compliments or contrasts with it. This could be used to enhance the overall vibrancy of the tapestries, which had fallen out of favour owing to their more subdued tone.

Colour circle, Michel Eugène Chevreul, Figure 6 from Expose d'un moyen de definir et de nommer les couleurs d'apres une methode precise et experimentale… [Presenting a way to define and name the colours according to a precise and experimental method…] (1861). RS.17622

Although this idea had been widely explored by artists, it was Chevreul’s scientific approach, and his use of the increasingly complex colour wheel, which gave the theory credence. The Royal Society awarded him the prestigious Copley Medal in 1857, in part for his research on the contrast of colour. Chevreul’s work became hugely influential on the artists of the period, including both Impressionists and followers of the later movement towards the organisation of colour, such as the pointillist Georges Seurat.

By coincidence or perhaps frequency bias, I was watching the BBC’s recent production, Bridget Riley – Painting the Line, and was interested to learn how Seurat’s use of colour had influenced her art. Riley is considered a ground-breaking modern artist, whose optical paintings have a profound and sometimes disorientating effect on the viewer. So, it seems the colour wheels keep on turning.

The bridge at Courbevoie by Georges Seurat, 1886-87. Photographed on display at the Courtauld Gallery by Mike Peel, 2009. Wikimedia Commons