Jessica Miller visits the Science City exhibition at the Science Museum, and discovers how London grew to become a powerhouse for natural philosophy between 1550 and 1800.

I recently took the opportunity to visit the Science City exhibition at the Science Museum. Bringing together objects from the Science Museum Group, the King George III collection owned by King’s College London, and the Royal Society Library and Archives, the exhibition demonstrates how London grew to become a powerhouse for natural philosophy between 1550 and 1800.

What struck me most was the close relationship between craftsmen and natural philosophers. The craftsmen had the practical skills and tools to provide the instruments needed for scientific investigation. Working in close proximity, they were able to pool their different areas of expertise in response to the demand created by the burgeoning growth of experimental research.

This relationship has its roots in sixteenth-century England, when Elizabeth I began to encourage tradesmen and craftsmen to set up shop in London. Many came from cities in continental Europe such as Augsburg and Nuremberg which had benefitted by attracting clusters of skilled instrument-makers.

Among the objects on display are the creations of Elias Allen (1588-1653), a tradesman from Tonbridge who specialised in sundials and other scientific devices. One example is a compendium which could function as a sundial, compass and calendar. Made between 1630 and 1653, it’s an example of the intricate and precise instrument-making of the period: Compendium by Elias Allen (Victoria and Albert Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Compendium by Elias Allen (Victoria and Albert Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

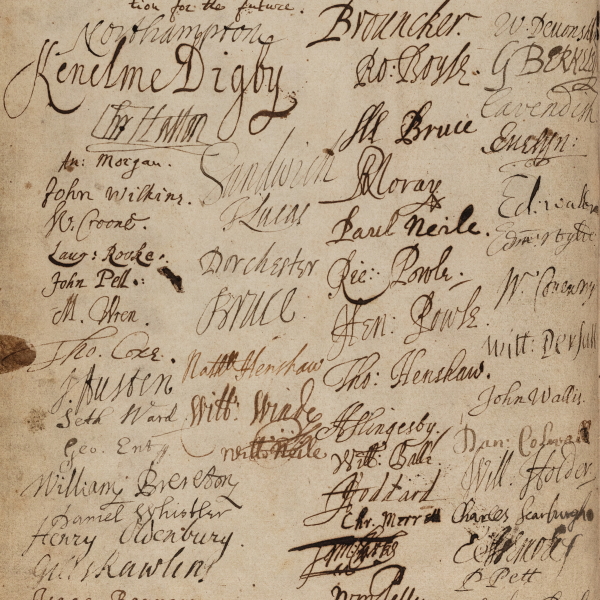

By the time the Royal Society was founded, with the aim (as set out in the minutes of the first meeting on 28 November 1660) of promoting ‘Physico-Mathematicall Experimentall Learning’, London had an abundance of capable engineers and instrument-makers. Great emphasis was placed on practical experimentation, and while Oxford and Cambridge remained the academic centres of the day, London provided a nucleus of highly skilled professionals who could create and supply the instruments required. This helped to foster close links between Fellows of the Royal Society and instrument-makers.

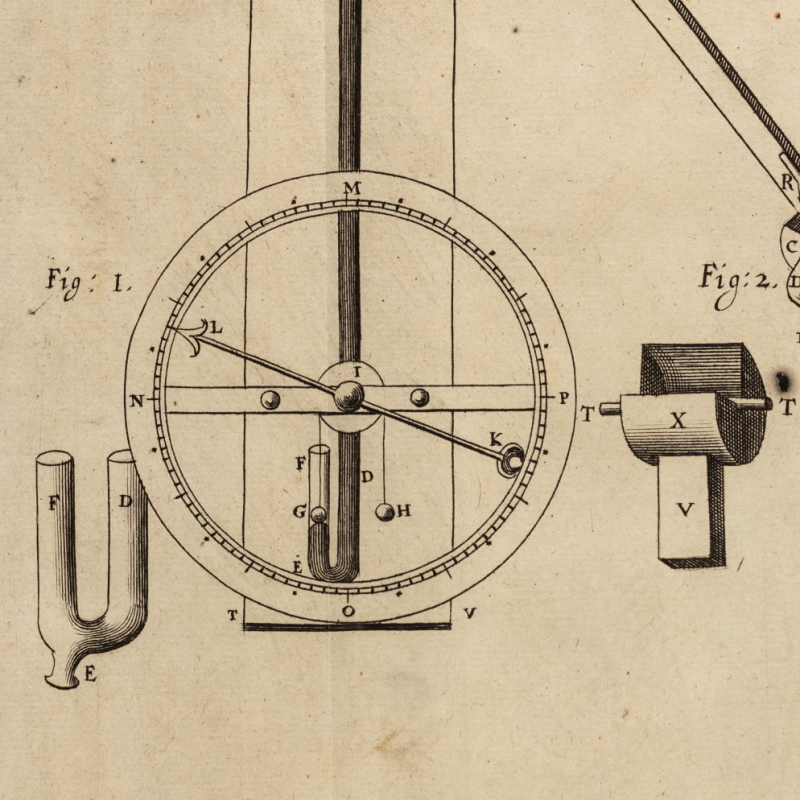

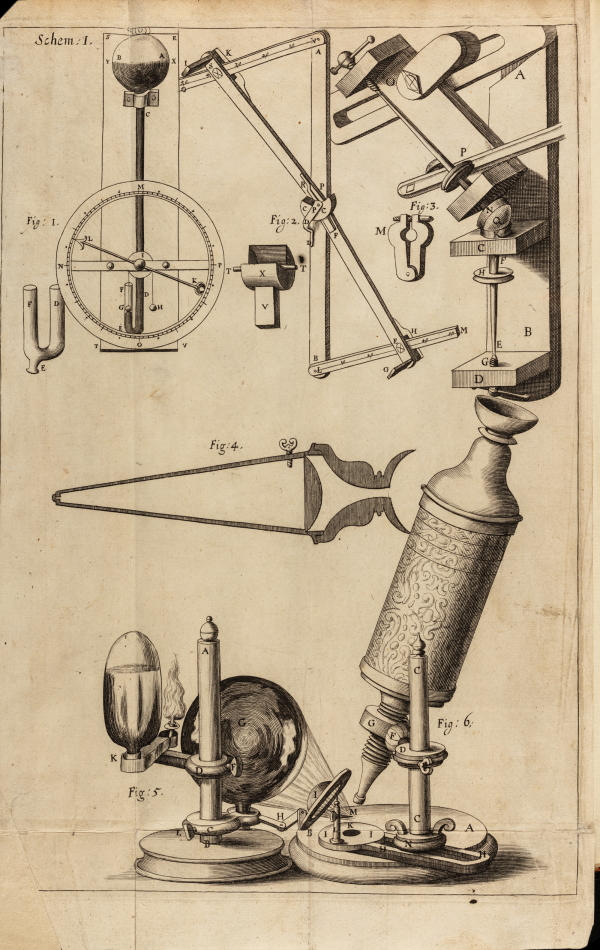

One of the key early Fellows, Robert Hooke FRS (1635-1703), rose to fame with the publication of his Micrographia (1665). This was a beautifully illustrated book depicting some of the specimens viewed by Hooke using microscopes of his own design. These were made for him by Christopher Cock, a specialist in optical instruments who forged a close working relationship with Hooke.

A Hooke microscope: plate I of Micrographia (1665)

There was also a growing public appetite for knowledge and demonstrations of natural philosophy. New developments in engineering, horology and other disciplines ran parallel to the rise in experimental philosophy, and the public wanted to see more.

A collection of Stephen Demainbray’s equipment demonstrates the style and content of lectures at this time, wherein objects including model gauges and engines were used to demonstrate the fundamentals of optics, mechanics and astronomy to eager audiences. Educated at Westminster School and Leiden University, Demainbray studied natural philosophy before teaching at Edinburgh University. During the 1750s, after his return to London, he gave a series of public lectures, using the impressive collection of over a hundred scientific models and devices he had amassed.

Optical model of a spectrum with inverted colours, owned by Stephen Demainbray (King’s College London, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Demonstrations that showcased the spectacular were particularly popular with the public. Optical models were used to show how spectra could be brought into focus, and objects that utilised electricity, such as chimes, were also very well-received. Most notably, Stephen Gray FRS published an account of the ‘flying boy experiment’, in which a static charge was transferred to a boy’s feet. This charge could then be detected by someone else nearby, and transferred via touch between audience members as a visible spark.

Electrical chimes made by George Adams, 1781-1790 (King’s College London, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Science City exhibition contains many fascinating and beautiful objects, which help to show how craftsman and natural philosophers came together in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century London. Combined with a growing public interest in experiment and spectacle, London’s place on the world’s scientific stage was firmly established.

To find out more about the ways London and science shaped each other, join our Stories from Science City event on Wednesday 1 December. Bringing together experts from the Royal Society, the Science Museum and the University of Cambridge, the event will explore the people, objects and stories behind the objects in the Science City gallery.