Royal Society Lisa Jardine Grant recipient Claire Conklin Sabel hunts for 'Rich & precious Stones' in the Society's collections.

In December 1678, the Fellows of the Royal Society turned their attention towards gems, or in their words: ‘the production of our owne Country as to Rich & precious Stones’.

Several weeks earlier, they had examined some minerals brought in by the Society’s Vice-President, Thomas Henshaw. Those present agreed that Henshaw’s stones ‘seem’d as good if not to exceed the Indian agates’, and so he ‘resolved to have them cutt & polished in ye like manner’ to bring in at the next meeting. Henshaw returned with the polished specimens, which ‘were as hard & bore a good a polish as agates’. Like the true agate, a form of quartz with distinctive banding patterns, Henshaw’s were observed to reveal ‘a very beautiful variety of colour & Spotts in them’.

Further discussion of gemstones was delayed by the Society’s anniversary on Saint Andrew’s Day, but resumed on 5 December. The meeting minutes record that on the question of England’s gemstones, ‘Mr. [Robert] Hooke affirmed it possible to make as good aggat cupps as any brought from the Indies out of certaine Flints & other stones plentifull enough here in England’.

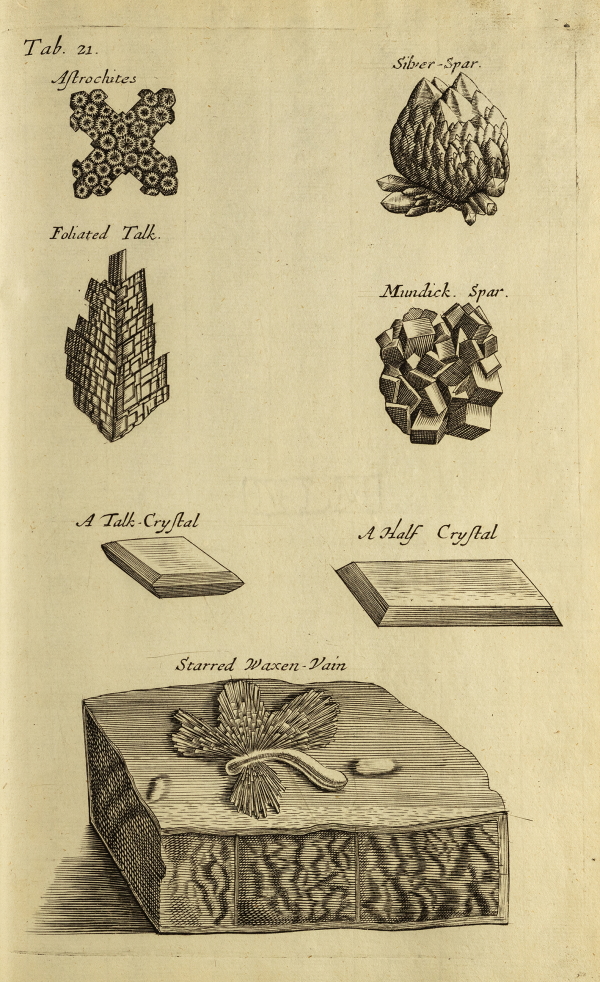

Crystal and mineral specimens: plate 21 from Nehemiah Grew’s Musaeum Regalis Societatis, 1681

As a historian studying the connections between earth sciences and economic activity, several things interest me about this episode. Firstly, an unnamed artisan to whom Henshaw took his stones for polishing played a crucial role in revealing the minerals’ structure and appearance. Such expertise was readily available in London, which was rapidly becoming one of the world’s major markets for precious stones. Secondly, over several meetings, there was a consistent association of agate with the ‘Indies’. In this period, the term denoted most of the Asian continent – from South Asia to China – but the terminology nevertheless conveyed that minerals had distinctive geographic distributions: mapping newly available commodities could provide Fellows with some insight into the Earth’s mineralogical diversity. Finally, Fellows’ interest in the raw material was directly related to its desirability as a crafted object, in this case an ‘agate cup’. Altogether, these features indicate strong connections between the Royal Society and the world of trade in the late seventeenth century, especially via the growing importance of mineral commodities from Asia, imported by the East India Company and private merchants to London.

Chinese Qing dynasty agate libation cup, 1644. Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

As geologists well know, looking at specific minerals within their broader context also tells you much about the Earth’s history and its physical and chemical processes. So too with archival gems: I found the analysis of agates amidst multi-faceted discussions of Earth-related phenomena, sustained over several months. In its early decades, the Society was deeply concerned with the composition and dynamics of the globe, from earthquakes and volcanoes to the sources of groundwater and the origins of metals and precious stones. From agates, the conversation soon turned to other terrestrial matters, such as potential sources of the Earth’s heat that could cause the underground fires then burning in Newcastle coalmines.

My doctoral research uses precious stones to gain new insights into the historical relationship between the earth sciences and extractive industries. Through the networks of the growing British Empire and overseas commerce, seventeenth-century Fellows had unprecedented access to information and material evidence of the world’s mineral resources. They also sought and collected information about the economies and expertise of the labourers and artisans who mined and crafted stones in South and South-East Asia, the source of most of the world’s gems at that time. A 1664 query for travelers to Asia asked for information on ‘what Art the Master workmen of Pegu [Burma] have to add to the Colour of theire Rubies’, and the Philosophical Transactions published an important first-hand account of diamond mining in the Deccan in 1677.

While the Society relied on travellers and merchants to inform them of the situation on and under the ground abroad, it benefitted from the local trade of jewellers and goldsmiths in London. As a Royal Society Lisa Jardine Grant recipient, I spent several weeks looking for gems in the Society’s archives. I was searching for those few precious nuggets that, when extracted, polished and set against a new background, might reveal something of the Society’s connections to the seventeenth-century global economy, while also trying to understand how concerns with cut and polished stones fit into the period’s broader philosophical questions about what the Earth is made of.

John Chardin FRS (RS.9680)

My time in the Library was therefore split between examining how gemstones and jewellers featured in discussions about Earth-related topics, and the ways that gem merchants contributed to the Society itself. Many prominent members of London’s gem trade participated in the Royal Society, either as Fellows or as guests. The French traveller Sir John Chardin, court jeweller to Charles II, was a Fellow, and visitors included ‘Monsieur de Bruin, of Antwerp, that have lived many years in England, skilfull in Jewells and Mettalls’, who was invited by Secretary Henry Oldenburg to attend a discussion of diamonds in a meeting on 18 November 1663.

Henry Oldenburg FRS (RS.9673) – note the diamond ring on the little finger of his left hand, shown magnified in the image at the top of this article

In June 1678, Sir Robert Vyner, supplier of the Crown Jewels for Charles II and Royal Goldsmith for almost thirty years, was present at a meeting. Because attendance was low that day, Vyner was shown around the Society’s Repository, which had an impressive array of precious stones within its mineralogical collections.

To find out more about some of the jewellers and goldsmiths who interacted with Fellows, such as ‘Monsieur de Bruin’, I was also able to use the Jardine grant to head to the historical centre of the goldsmiths’ trade in the heart of the City. There I visited the library of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, whose guild records date back to the fourteenth century. The Goldsmiths’ library records both the influx of gemstones to seventeenth-century London and the increasing presence of ‘stranger’ goldsmiths, who had escaped political and religious persecution elsewhere in Europe. Meanwhile, many of the stones they worked with were supplied by Jewish gem merchants from the Low Countries and Portugal, not least the prominent Mendes da Costa family: Emanuel, several generations later, would become the Society’s Secretary and a prominent mineralogist in his own right.

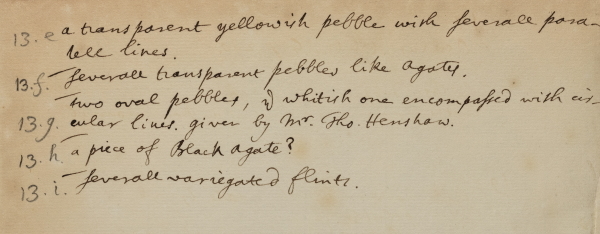

Page from Repository inventory MS/414, section 8 ‘minerals’

Unfortunately, I was unable to locate any actual gemstones long buried in the Royal Society’s collections. The Repository evidently had a considerable number of gems for some decades (as indicated by the inventories commissioned in the 1730s), and the minutes suggest these were actively used for experiments. In 1734, the Committee appointed to assess the State of the Repository noted that, compared to the animal and vegetable collections in various states of decay, the minerals were in better shape, with one exception:

‘The Committee are surprised to find so many curious specimens of oriental and other precious stones in the lists of Donations, not to be found in the Repository, notwithstanding their most diligent search’. (CMO/3/55)

The Committee advised that going forward, the remaining gems only be shown to visitors under strict surveillance.

While the stones themselves may be long gone, the gem trade left its traces among the Society’s archives, and I would not have been able to spend the time carefully sifting through them without the support of the Jardine grant. However, while Fellows occasionally mentioned London goldsmiths by name, we know far less about the other end of the supply chain: the labourers and artisans who dug, sorted and faceted precious stones close to their sources. It was they who had worked and developed mines over centuries, within vastly different scientific, political, and economic conditions. Learning more about them will be the next stage of my research in the Netherlands, Indonesia and India.