Jon Bushell explains how procedures for admitting new Fellows to the Royal Society have changed over the centuries.

June and July are always busy months here at the Royal Society. This year, the start of July saw the return of our Summer Science Exhibition as an in-person event, after the previous two were held online. Admission Day, where newly-elected Fellows and Foreign Members are formally admitted into the Society, also takes place at this time of year, and 2022 has been particularly hectic: lockdowns and travel restrictions in 2020 and 2021 meant that we had to catch up and run three separate ceremonies this year.

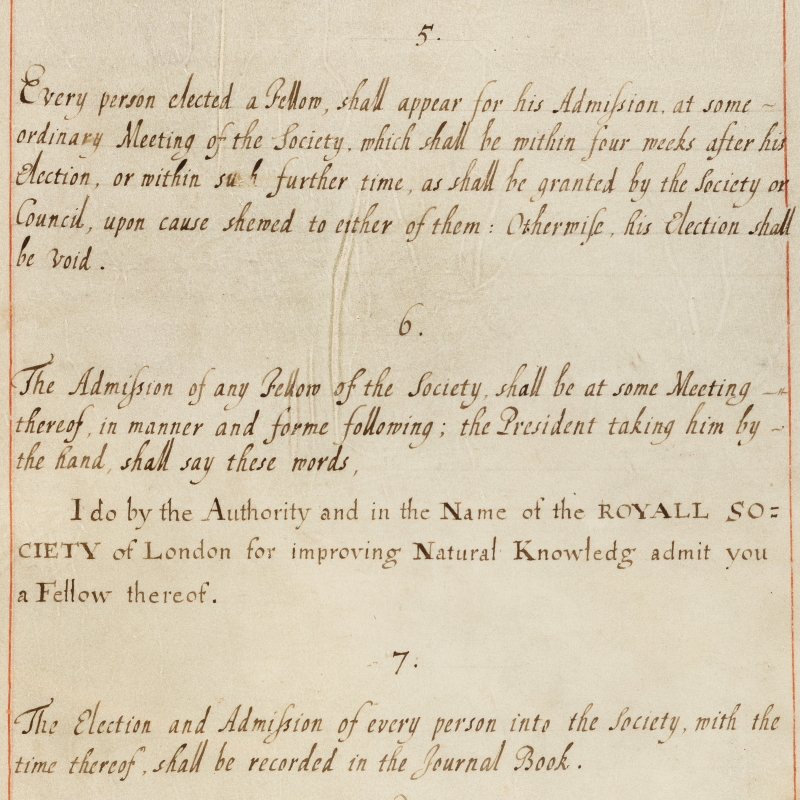

One question that cropped up several times was about the history of Admission Day, and whether new Fellows were always admitted at a ceremony like this. Since the enactment of the first statutes of the Royal Society in 1663, there has always been a distinction made between a Fellow being elected to the Society and being admitted to the Society. However, there was no specific day for admitting new Fellows, and instead admission took place at one of the Society’s ordinary meetings.

Initially, the statutes stated that elected Fellows should be admitted within four weeks of their election. In 1847 this was changed so that admission had to take place on or before the fourth meeting after election instead. The Council also frequently granted extensions to Fellows who couldn’t make it to an ordinary meeting in time.

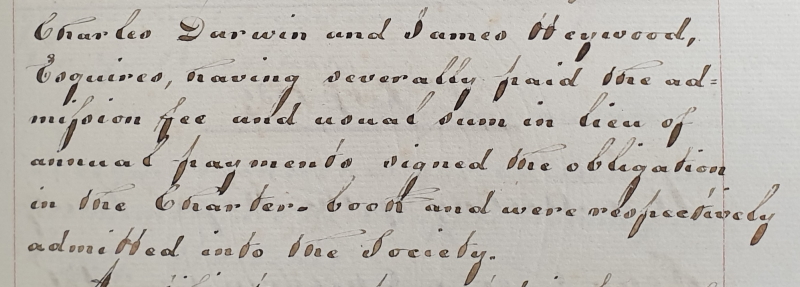

From the minutes of the meeting on 14 February 1839, where Charles Darwin and James Heywood signed the Charter Book and were admitted into the Royal Society

From the minutes of the meeting on 14 February 1839, where Charles Darwin and James Heywood signed the Charter Book and were admitted into the Royal Society

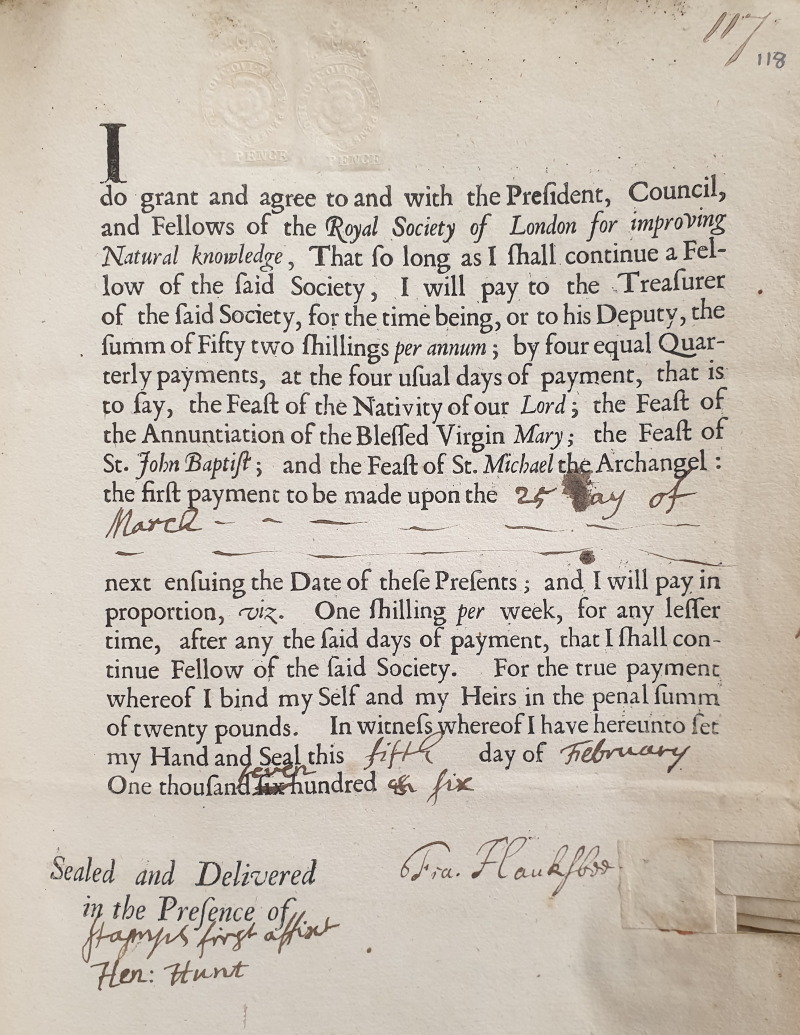

When Fellows presented themselves to be admitted, they had to subscribe to the obligation of the Society, sign the Charter Book, and (most importantly) pay their fees. In 1663, Fellows paid forty shillings (£2) on admission, and thereafter one shilling a week, in quarterly instalments. By 1847 this had increased to £10 up front and another £4 per year, with lifetime payment options starting at £40 for those who could afford it.

Francis Hauksbee’s bond with the Royal Society, agreeing to the payment of the Society’s fees, signed on 5 February 1706 (MS/390)

Francis Hauksbee’s bond with the Royal Society, agreeing to the payment of the Society’s fees, signed on 5 February 1706 (MS/390)

Overseas Fellows were exempt from paying subscription fees, and Council also had powers to waive fees if Fellows found themselves in financial hardship. But subscriptions made up a large part of the Society’s finances and non-payment of dues could be punished by expulsion from the Fellowship. Every so often, particularly at times where the Society’s finances were looking precarious, Council would crack down on those Fellows in arrears, and several were ejected for not paying up.

The Charter Book contains the text of the Society’s charters and statutes, and the obligation Fellows subscribe to upon being admitted; it was also designed to serve as a ‘Register of all the Fellows of the Society’. Jonathan Goddard FRS was directed by Council to prepare the book in October 1664, and the first signature to be entered into it was that of Charles II, when the book was presented to him on 9 January 1665. Many Fellows elected prior to its creation had already signed the first Journal Book but were encouraged to sign the Charter Book as well.

Charles II’s signature in the Charter Book

In the three admission ceremonies in 2022, 151 Fellows and Foreign Members signed the Charter Book. This was almost certainly our most prolific year ever for gathering signatures of new Fellows. 1665 might be a close second; there are 144 signatures in the book from Fellows elected from 1660 to 1665, including those on Charles II’s ‘royal page’ and several honorary signatures from foreign dignitaries. But even if we presume all these signatures were added in 1665 (which seems unlikely), 2022 still takes the crown.

Despite the Society’s best efforts, it was inevitable that some elected Fellows would miss signing the Charter Book. Many of these were Foreign Members who never travelled to England. Others missed out for personal reasons: Francis Willughby, one of our early Fellows, had signed the Journal Book when he was elected in 1663, but his father’s ill health forced him to leave London in 1664, and his own untimely death in 1672 meant he never signed the new Charter Book.

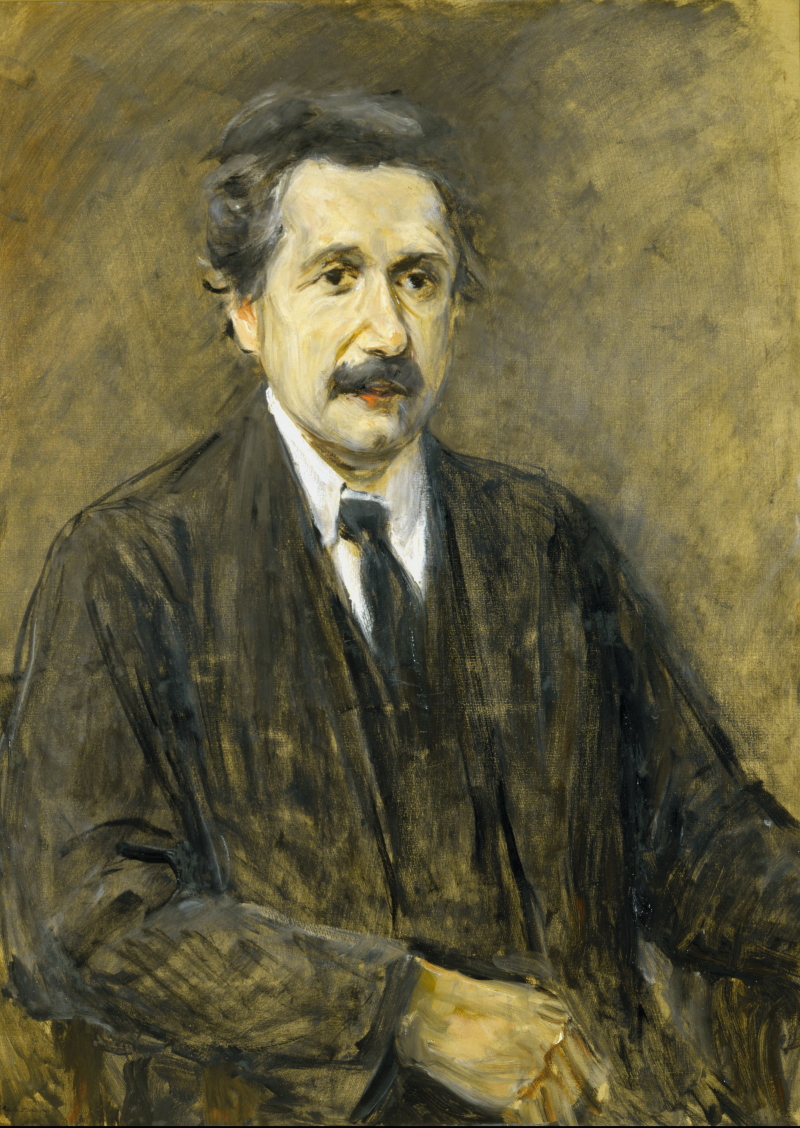

In total, around 1,240 elected members have missed out on signing the Charter Book since 1665. Probably the most regretted omission is Albert Einstein, elected a Foreign Member in 1921; despite his spending time in London in the 1920s and 30s, the Society never managed to pin Einstein down and get him in the book.

The Royal Society’s portrait of Albert Einstein (RS.9246)

The Royal Society’s portrait of Albert Einstein (RS.9246)

Reforms to the Fellowship election process in the 1840s meant that elections took place annually, instead of candidates being balloted throughout the year. Consequently, several new Fellows would often appear at the same meeting for admission following their election. This took up significant amounts of time, and by the 1940s meetings were being arranged where the only business was the admission of new Fellows. Admissions continued to take place at ordinary meetings well into the twentieth century, although not exclusively: the Journal Books show that some admissions were taking place over the summer recess, with the dates of admission then reported at the first meeting back in November.

By the 1980s Fellows were almost exclusively being admitted outside of meetings. At the meeting on 12 June 1986 it was reported that 36 Fellows had been admitted to the Society on various dates through April and May, following the election meeting in March. Almost all the admissions for 1989 took place on 8 June, and all the admissions for 1990 were handled on 7 June. Although the changes had clearly happened gradually, by this point the admissions process looks very similar to that of today.

One final significant change: the steel dip ‘quill’ pens which were used to sign the Charter Book until at least the 1990s have been replaced by fountain pens. Though we do still have a few quills lying around in case there are any future Fellows who’d like to try using one. Just try not to blot the Charter Book.