Keith Moore discovers examples of the overlooked, the ephemeral and the downright weird in the files of the Royal Society.

One of the pleasures of working with papers that haven’t been looked at for decades, is that sometimes items evade the best efforts of archivists to keep tidy and relevant files. The overlooked, the ephemeral and the downright weird sometimes survive – either because these normally fleeting items don’t get weeded from files, or they shouldn’t have been there in the first place. I love to find the things that distracted clerks have tucked away in a moment of absent-mindedness.

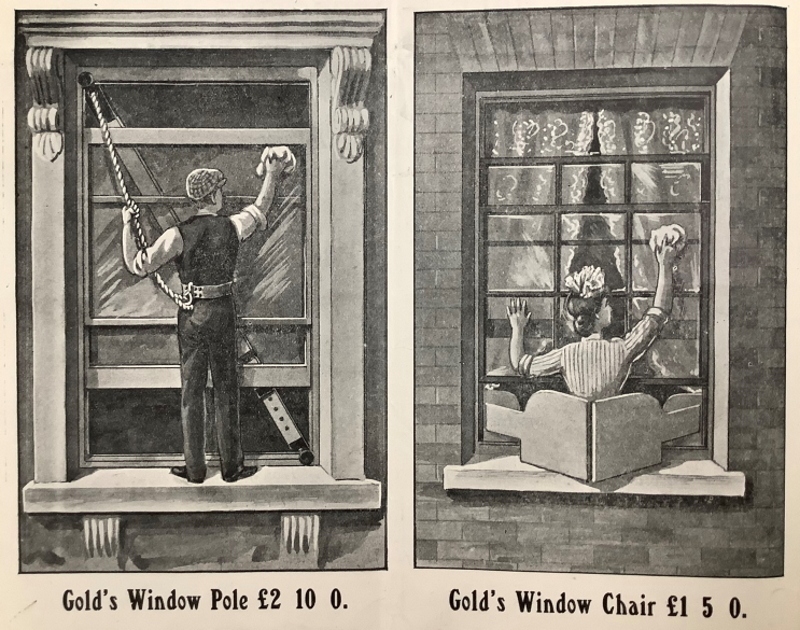

Recently, I’ve been listing internal Royal Society files, some of which shed light on the humdrum business of what it takes to run a scientific academy. Not the great science, but how electric lighting was introduced to the Society’s Burlington House headquarters building, and what sort of vacuum cleaners you might find being used. The introduction of new technologies in domestic settings is a topic of interest to historians, but I don’t believe they had in mind this rather wonderful period advertisement for H. Gold’s window-cleaning safety equipment:

All that glitters: advertisement for Gold’s safety appliances

All that glitters: advertisement for Gold’s safety appliances

Clearly, the late Victorians were becoming a little more safety-conscious than Alfred Tennyson (rather incongruously elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1865), who would climb out of Burlington House windows to smoke on the roof when visiting his brother-in-law, the Royal Society’s Assistant Secretary, Charles Richard Weld.

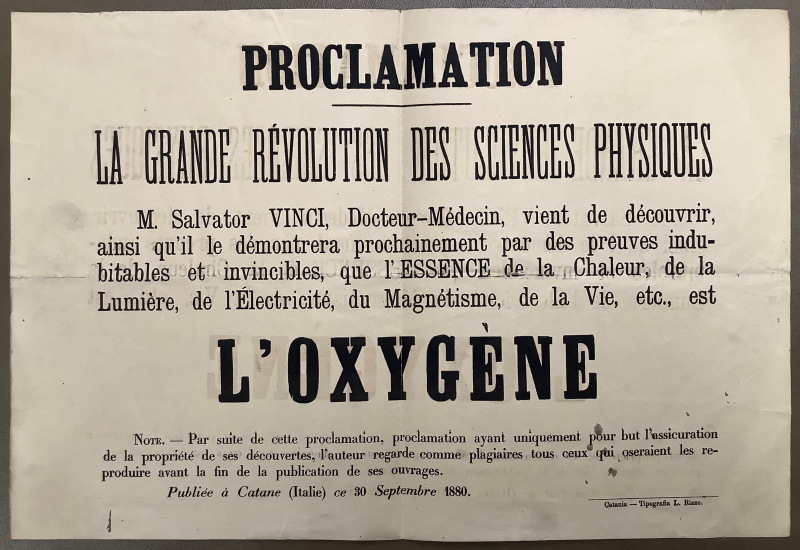

Elsewhere, slipped into the same batch of correspondence, I came across an eccentric (to say the least) 1880 flyer, produced by Salvator Vinci. Vinci may be a promising name for a scientist and polymath, but this proclamation of a grand unified theory of everything – citing indubitable proof that oxygen is the essence that would revolutionise the physical sciences – is hardly up there with Leonardo’s Arundel Codex. It seems to have been used as scrap paper, so Vinci’s claims remained cruelly uninvestigated.

A ‘great revolution’ in physical sciences, from 1880

A ‘great revolution’ in physical sciences, from 1880

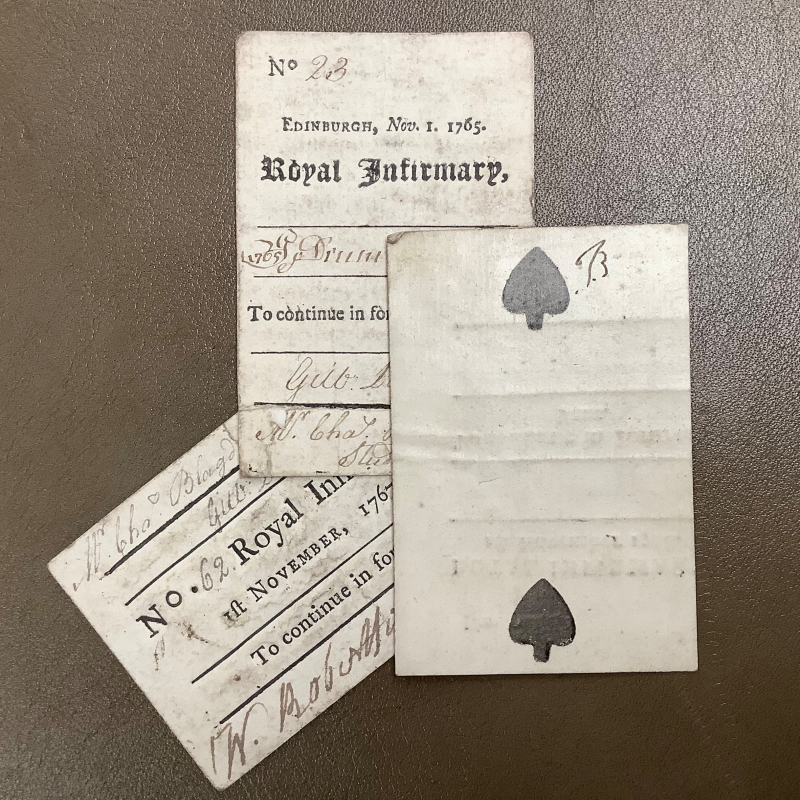

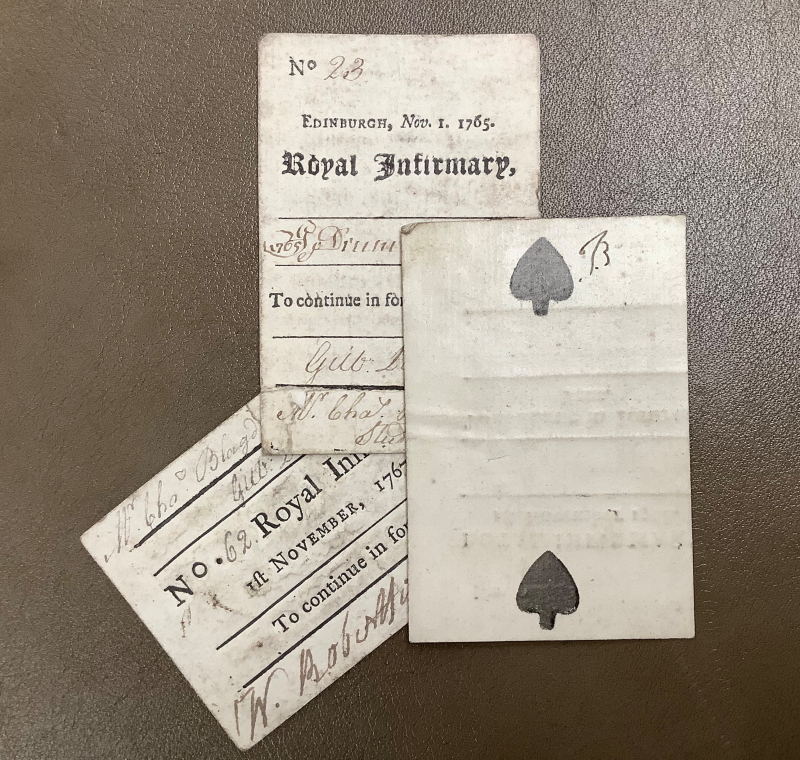

Such things are strictly one-off survivors, but there are those who have collected ephemera in a more systematic way. Like many in the circle of Sir Joseph Banks, Charles Blagden (1748-1820) was something of a magpie for accumulating paper, and his archive is a treasury of the slightly useful. Blagden began his scientific career as an Edinburgh-trained physician, graduating as M.D. in 1768. He kept Royal Infirmary passes from this time, amusingly re-purposing them as playing cards. I suppose it provides a snapshot on both the training of medical students and how attentive they were to their lecturers.

Play trumps work: cards from Charles Blagden, 1765-67

Play trumps work: cards from Charles Blagden, 1765-67

Much of the surviving printed material is actually quite serious, reflecting the concerns of Blagden’s time, such as information from scientific instrument makers, canal engineers and the promoters of medical and chemical ‘cures’. Some of the best pieces are the printed ephemera from the Royal Society and the Royal Institution. The former includes items not kept elsewhere in the Society’s collections and so valuable institutional history, including those on Blagden’s own candidature for the post of Secretary of the Royal Society, in competition against Charles Hutton (1737-1823). The election was controversial, with Banks tipping the scales, which led ultimately to Hutton’s resignation from the Fellowship.

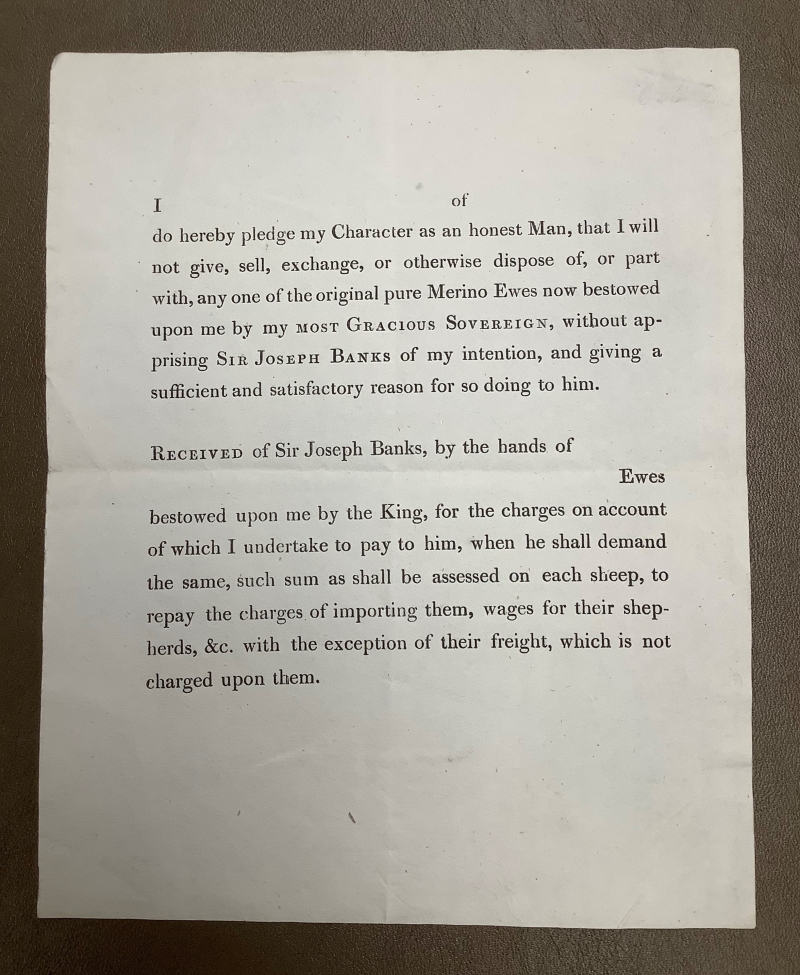

My favourite piece of ephemera kept by Blagden and relating to Sir Joseph Banks, is Banks’s firmly worded form of receipt for stock of Merino sheep. Agricultural improvement, including sheep-breeding, was a shared interest of the land-owning President of the Royal Society, and King George III. After an initial foray by Banks into smuggling Merino rams and ewes from Spain, via Portugal, the King managed to obtain some official Merinos from his Spanish counterpart in 1791. The form of receipt shown must follow from that date, with Banks admonishing the ‘honest Man’ to report to him before any sales of livestock could be made, and to make sure that any fees were covered. So, literally an I.O.Ewe, and worthy of preservation on those grounds alone.

He won’t be fleeced: Sir Joseph Banks manages sheep (CB/4/11/7)

He won’t be fleeced: Sir Joseph Banks manages sheep (CB/4/11/7)