Research projects on Sir Humphry Davy’s manuscript notebooks and letters are revealing new and candid details of Davy’s life and career, as Andrew Lacey illustrates, drawing on material held in the archives of the Royal Society and elsewhere.

By November 1822, two hundred years ago, Sir Humphry Davy had occupied the President’s Chair of the Royal Society, made vacant by the death of Sir Joseph Banks, for two years.

His election to the Presidency had, as scholars (such as Lionel Felix Gilbert and David Philip Miller) have long recognised, been a rather treacherous affair: as the editors of the recent Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, published in four volumes with Oxford University Press in 2020, summarise, Davy had run ‘a concerted campaign that involved undermining the candidature of his friend William Hyde Wollaston and attacking his former patron’ Davies Gilbert. This was conduct that several with an eye on the election (rightly) found distasteful, and considered ‘ungentlemanly’.

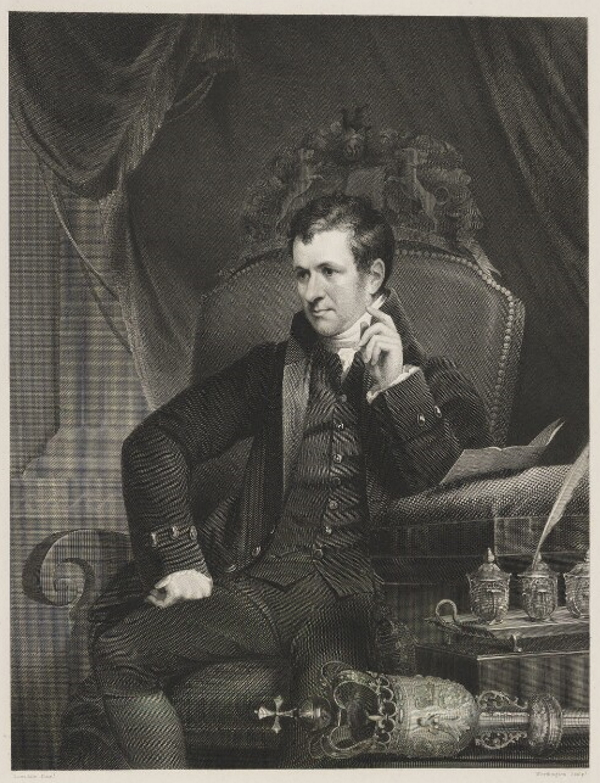

Davy in the President’s Chair, line engraving, published March 1827. National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG D34825). Reproduced under the terms of CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Letters that were unpublished until recently, some held in the archives of the Royal Society, shed new light on Davy’s calculated campaign towards securing the Chair. On 23 May 1820, some six months before election day (St Andrew’s Day), Davy wrote to Charles Hatchett, the chemist and mineralogist (Royal Society MS/859/2/34):

‘When we last discussed together the subject of the presidency of the Royal Society & I told you I should decline becoming a candidate, it was on the supposition that the Society would either look to some man of high distinction in the Society from his scientific labours such as yourself or Sir E. [Everard] Home, or some man of exalted rank large fortune & independency of character as Lord Spencer [George John Spencer, 2nd Earl Spencer] … it never occurred to me that a gentleman … who had never published a single paper in the Transactions & whose importance in society arose from his being an active though not an independent member of parliament could be proposed.’

This is a (barely) veiled attack on Gilbert, who was Banks’s preferred successor to the Chair, and who eventually did succeed Davy to the Presidency after his uneasy tenure came to an end in 1827. Davy continues:

‘Wishing to prevent the appendage of the chair of the Royal Society to a rotten cornish borough & feeling deeply for the interest & the honour of that body, I should willingly make any sacrifices or take any part & throw my weight into any respectable scale to prevent the gentleman in question from occupying a situation to which there are at least 40 members in the Society who have higher claims.’

Gilbert (formerly Giddy), MP for Bodmin from 1806 and mentor and patron to Davy in his early years, may well have been wounded by his protégé’s scheming, had he known what he was up to. In the letter to Hatchett, Davy states a preference for Lord Spencer (rather than, at this stage, himself) as President, albeit in slightly backhanded fashion, describing him as ‘the most unexceptionable’ candidate. By 23 June 1820, Davy had plainly reconsidered, as a letter to William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale, held in the Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle, reveals:

‘I have been encouraged by a great part of the most distinguished Members of the Royal Society including Lord Spencer & two gentlemen who have been thought of as presidents [possibly Everard Home and Prince Leopold] to offer myself as a candidate for the vacant chair ... I have no party feelings no private views on the occasion My desire is to devote my life to Science & to the scientific interests of my country & I seek this honorable station only because I hope it will afford me more power of being useful & gratify an honest ambition’.

While Davy’s ‘ambition’ may indeed have been ‘honest’, his private dealings with potential supporters and, crucially, those who he saw as influential figures who might still have a bearing on the outcome were rather less transparent. Writing to Gilbert (he of the ‘rotten cornish borough’) on 25 June 1820, in a letter held in the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Davy flatters Gilbert, attributes to him almost god-like powers of ‘prophecy’, and, somewhat shamelessly, calls on him to ‘be [his] friend’ – this, of course, being the man whom Davy, who was encouraged in his youthful chemical researches by Gilbert, had clandestinely denigrated only a month earlier.

Gilbert had recently withdrawn his candidacy, and Davy clearly saw an opportunity to bring him onside. In the letter, which is headed ‘Private’ in Davy’s hand, there is no mention of Banks’s own preference for Gilbert, or of Gilbert’s own ambition to be elected President; now that Gilbert had withdrawn, neither apparently mattered to Davy. With Gilbert out of the frame, Davy quickly turned his attention to Wollaston. In another letter dated 25 June 1820, held in the archives of the Royal Society (MM/6/87), Davy wrote to Wollaston, the chemist, physicist, and physiologist, and a fishing companion of his:

‘I solemnly assure you that if on my return from Italy I had found you a candidate for the chair of the Royal Society & supported as you always must be by your friends & by public opinion nothing would ever have induced me to enter into competition with you.’

But ‘enter into competition’ with Wollaston Davy had. This letter is emollient in tone, as Davy recounts feeling ‘severely wounded when I became acquainted with the active & extensive canvass of many of your friends [including Charles Babbage, John Frederick William Herschel and Captain Henry Kater] against me at a time when I was almost reposing on the hopes of your support’. Davy continues: ‘This wound however you have healed & the manner in which you have done so has increased my admiration of your character’: Wollaston had declined to run, and instead agreed to serve as interim President until November 1820, when Davy would eventually be elected to the Chair. In his letter to Wollaston, despite its seeming magnanimity, Davy’s self-interest is evident:

‘Should I be elected president I can not perform the duties of the office or promote the great objects of the Society unless I am supported by the good opinions of yourself & your friends I hope therefore that no one will retain a feeling of irritation & that if any thing foolish or angry has been said on the occasion it will be forgotten.’

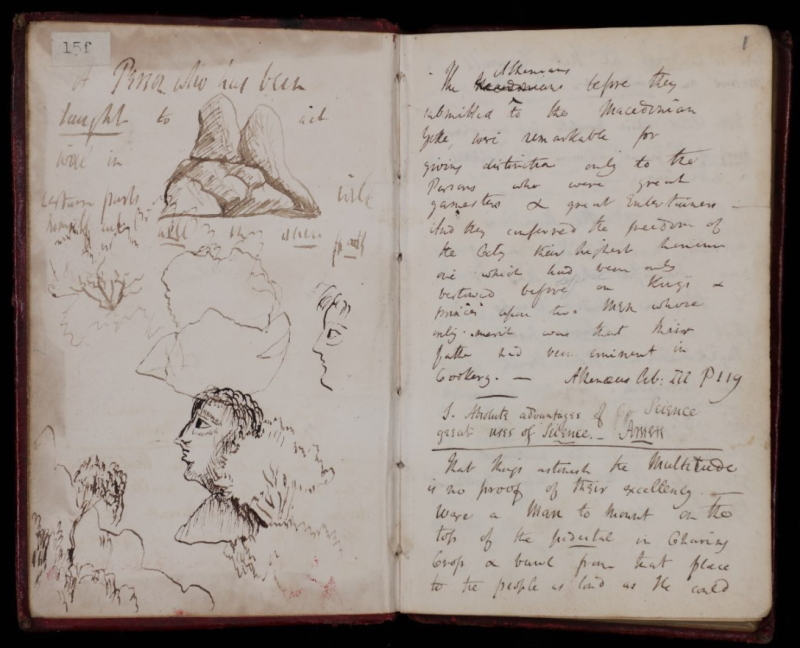

Manuscript sources such as these letters provide revealing, often fascinating, insights into Davy’s character and private, sometimes ruthless, dealings with others in his professional sphere. Following on from the publication of Davy’s letters, work is currently well underway, using the people-powered research platform Zooniverse, to transcribe his c. 75 manuscript notebooks, held in the Royal Institution and Kresen Kernow. Davy’s notebooks, many richly detailed with sketches, are generically mixed, containing records of his chemical researches, poetry, and material encompassing philosophy, geology, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and more. While working on these valuable documents (the majority of which have never been transcribed before), we are learning more every day about Davy, his life, and the cultures and networks of which he was part.

Front endpaper and p1 of Davy notebook RI MS HD/15/F (c 1805). Courtesy of the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

Front endpaper and p1 of Davy notebook RI MS HD/15/F (c 1805). Courtesy of the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

The Davy Notebooks Project team warmly invites readers of the Royal Society blog to get involved with the transcription process, the final product of which will be a free-to-access online digital edition of Davy’s entire notebook collection. Although Davy emerges rather badly, as a truer picture is pieced together with the help of unpublished material, from instances such as the lead-up to his election to the Presidency of the Royal Society, we are gaining a better sense of the complexity of his character – his idiosyncrasies, his sensitivities, his immense ambition – as we work through the notebooks, as well as gleaning new details of his chemical researches, experiments in poetry, and travels. Who knows what you might find in Davy’s private writings?