Ellen Embleton explains how her research into two pairs of portraits, featuring Fellows of the Royal Society, can help us understand them as representations of real people in a specific historical context.

Until the last few decades, the Royal Society’s portraiture collection has been seen largely as a source of decorative exhibition material, and its immense historical value has been under-researched. This leaves the Society’s portraiture feeling somewhat unknowable to audiences, which is further exacerbated when works lack basic interpretative information, such as sitter identities, dates of creation, and artists.

The ‘Seeing Clearly’ project, funded by the Understanding British Portraits network, sought to tackle this problem by researching two little-known late seventeenth and early eighteenth century portrait pairs.

They feature Abraham Hill FRS (1635-1722) and a (previously) unknown lady from the Hill family [above], and Sir Cyril Wyche FRS (c.1632-1706) and an unknown lady from the Wyche family [below]. The project sought to answer the question: how can we enable audiences to see these portraits more clearly?

By comparison to famous early Fellows such as Wren, Boyle and Newton, Hill and Wyche are slightly more obscure figures, while little was known about their wives. A key step, therefore, was to bolster the biographical and contextual information we held on them via targeted, archival research.

Portrait of Abraham Hill, attributed to John Hayls, 1650s

Portrait of Abraham Hill, attributed to John Hayls, 1650s

Hill’s commonplace books in the British Library indicate the breadth of his interests. Though mostly quoting from religious texts, they also cover antiquities (particularly ancient coins), moral philosophy, and science. A Founder Fellow of the Royal Society, our records demonstrate that Hill took his responsibilities as Council Member, Treasurer and Secretary seriously, with near perfect attendance at Council meetings from the 1670s to the 1710s. He advised the Society on multiple ‘high profile’ cases, including the Newton-Leibniz controversy, and sat on various committees.

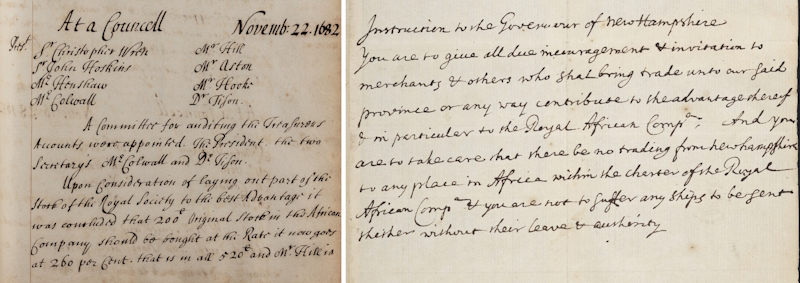

The Royal Society’s investment in RAC stock in 1682 [CMO/2/14, left], and Hill’s ‘Instruction to the Governor of New Hampshire’, Courtesy of the British Library Board [Sloane MS 2902, fol.87, right]

The Royal Society’s investment in RAC stock in 1682 [CMO/2/14, left], and Hill’s ‘Instruction to the Governor of New Hampshire’, Courtesy of the British Library Board [Sloane MS 2902, fol.87, right]

Excellent research previously undertaken on the Royal Society’s links to the Royal African Company (RAC) identified Hill as a key figure in securing the Society’s initial investment. Indeed, his administrative abilities were put to much use in English colonisation. As well as working for the RAC, he served as Commissioner of Trade and Plantations from 1696 to 1702. He appears to have supervised colonial affairs via close contact with governors for details of their administration, population, goods production and trade. His professional papers from this period evidence the many ways in which mercantilist policies were used to justify colonial expansion and the slave economy.

Portrait of Sir Cyril Wyche by an unknown artist, 1690s

Portrait of Sir Cyril Wyche by an unknown artist, 1690s

Wyche’s relationship with the Royal Society was less involved than Hill’s, despite his having served as Vice-President and President. He seems to have presided over Council Meetings from December 1683 to May 1684, when his attendance dwindled. This coincides with his increasing political responsibilities, particularly in Ireland, initially as secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and later as Lord Justice.

Acting as Lord Justice during the Williamite confiscations, Wyche refused to execute one of the most controversial of all royal grants of forfeited Irish lands, the estate of James II to William III’s reputed mistress, Elizabeth Villiers. He is said to have tried to carry through impartially and fairly the terms of the Treaty of Limerick (1691) and played a key role in the revival of the Dublin Philosophical Society as its President (1693). However, he was administrator for a governing body that promoted religious persecution and enforced its rule in a way similar to that seen in overseas English colonies.

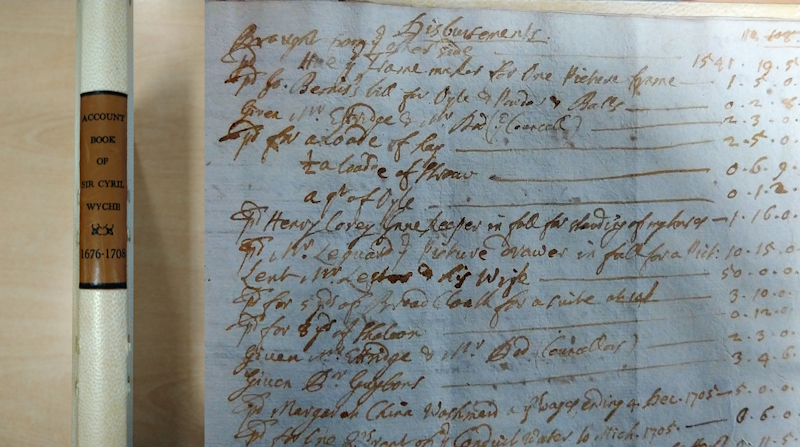

Wyche’s account book [left], including the record of a payment to ‘Mr. Lequard [Laguerre] ye Picture Drawer’ [right], Norfolk Records Office

Wyche’s account book [left], including the record of a payment to ‘Mr. Lequard [Laguerre] ye Picture Drawer’ [right], Norfolk Records Office

The Norfolk Records Office holds two of Wyche’s account books, one of which is particularly thorough and offers insights into his personal life. They evidence the fact that he was a stockholder in the East India Company (EIC) from 1699 to 1707, and a supporter of several ‘picture drawers’, including Peter Walton (1665-1745) and Louis Laguerre (1663-1721). Sadly, neither are believed to be responsible for the Society’s portrait; however, they point towards Wyche’s interest in pursuing artistic as well as scientific development.

Hill and Wyche’s biographies are an important reminder that England’s scientific revolution and its colonial expansion were often administered and funded by the same people. This naturally led to an overlapping of interests between bodies such as the Royal Society and the RAC and EIC. While Hill and Wyche’s portraits appear to have been commissioned prior to their investment in these colonial trading companies, inherited money is harder to speak for, and both families have long-standing ties to the Merchant Adventurers of London and EIC.

Research into the portraits of Lady Hill and Lady Wyche [?] began from a position of even less information. They were believed to be the wives of Abraham Hill and Sir Cyril Wyche, but each man married more than once.

Portrait of a woman of the Hill family, probably Anne Hill, by an unknown artist, 1650s

Portrait of a woman of the Hill family, probably Anne Hill, by an unknown artist, 1650s

The donor of Abraham Hill’s portrait noted in her correspondence with the Royal Society that, ‘I also have the portraits of his first + second wives - both equally fine’. However, by the time of the above portrait’s accession in 2020, certainty of which woman it depicted was lost, and it is unclear what happened to the second portrait.

Using the Heinz Library’s reference collection, this project has analysed the sitter’s dress to narrow down the date window. The results have increased confidence that this is Anne Hill, Abraham’s first wife, rather than Elizabeth Hill, whom he married later, or indeed any other woman of the Hill family. Sadly, Anne is largely absent from the family papers at the British Library, appearing only once in the will of Agnes Hill, who bequeaths her ‘all my hoods, scarfs, night cloths, & such like [...]’. Her and Abraham’s marriage settlement is held at the Kent Records Office, but this is a distinctly impersonal document. The only thing resembling a character account comes from her father Bulstrode Whitelocke’s diary, which describes her as ‘of a sweet condition & temper […] a hansom, proper young woman’ on her death in 1661.

Portrait of an unknown woman, possibly of the Wyche family, attributed to the Godfrey Kneller Studio, c.1700s-1720s

Portrait of an unknown woman, possibly of the Wyche family, attributed to the Godfrey Kneller Studio, c.1700s-1720s

The companion piece to Sir Cyril’s portrait unfortunately remains mysterious. Previously thought to be Mary Wyche (1648-1723) née Evelyn, this has not been confirmed by any Wyche family papers. Furthermore, its absence from Frederick Duleep Singh’s comprehensive listing in Portraits in Norfolk houses has been checked and verified, problematising its association to that of Sir Cyril. This obscures the identity of the sitter, making a biography impossible.

Thankfully, we have at least been able to reveal something about the artist responsible for her likeness, piecing together something of the work’s artistic lineage. Our conservator’s brilliant restorative work revealed a partial signature in the lower-right hand corner of her portrait, suggesting the hand of Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) is at play.

‘G Kne […] 17 […]’, believed to be the signature of Sir Godfrey Kneller

‘G Kne […] 17 […]’, believed to be the signature of Sir Godfrey Kneller

Where archival sources fell short with these women, visual clues in the portraits themselves were a great help. This is discussed further in two Google Arts & Culture exhibitions curated as part of the project, one on period fashion in the Hill family portraits and one on visual clues in the Wyche family portraits.

There is a certain mystification that takes place when portraits are separated from the context in which they were created, and it is the responsibility of heritage staff to provide clarity as far as possible. This research has simultaneously identified the challenges inherent to gathering data on artworks over 300 years old, and the importance of trying to do so nonetheless, to better understand them as representations of real people, from a specific historical context.