Louisiane Ferlier finds a few surprises on the 'Language and Literature' shelves of the Royal Society Library.

As it’s the season for holidays and travel, I wanted to offer readers a chance to join me on a tour of one of the lesser-known regions of our collections: the language and literature section.

With high levels of rain around, I secreted myself safely in our temperature-controlled vault to have a look at the intriguing classmark ‘Lang.& Lit.’. My primary motivation was to discover what remained in this category, which had been depleted by a Sotheby's auction in 1925. By the late nineteenth century, literature was considered outside the scope of the Royal Society Library’s collection, and soaring prices on the rare book market prompted Council to approve the sale of a Shakespeare Second Folio and the ‘Algonquian’ Bible amongst other treasures, in order to create a fund for the library to acquire scientific volumes.

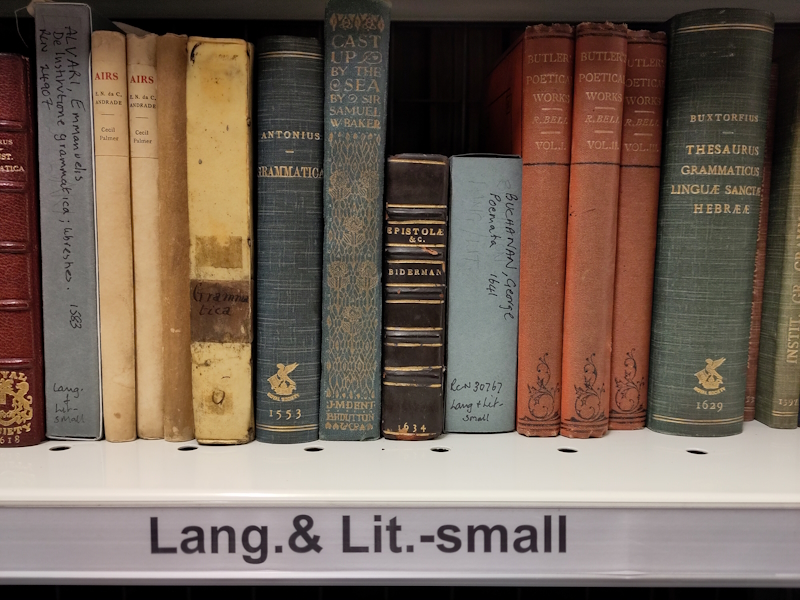

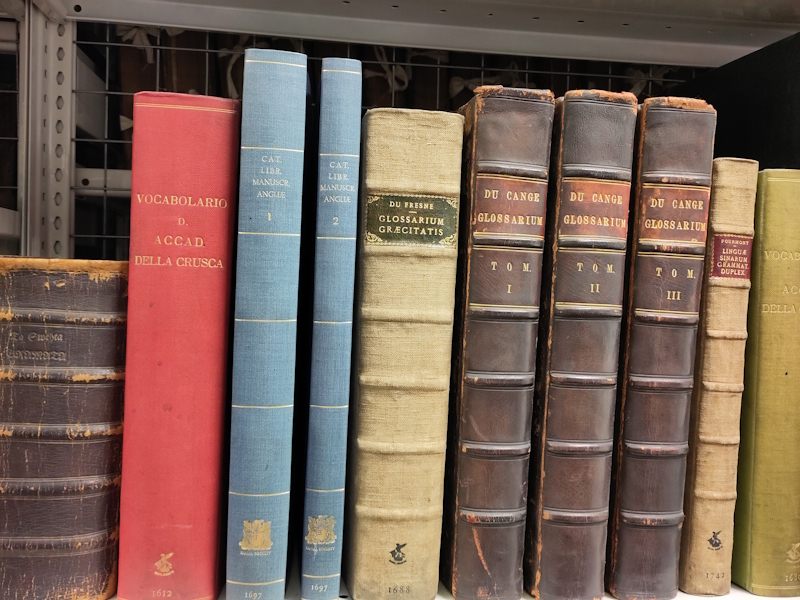

Still, we have a total of 348 titles in our current possession classified as ‘Lang.& Lit.’ All I knew of the classmark before my expedition was that it included the smallest volumes in the library, and that I had spotted a series of seventeenth-century dictionaries which clearly looked to have been Grand Tour classics.

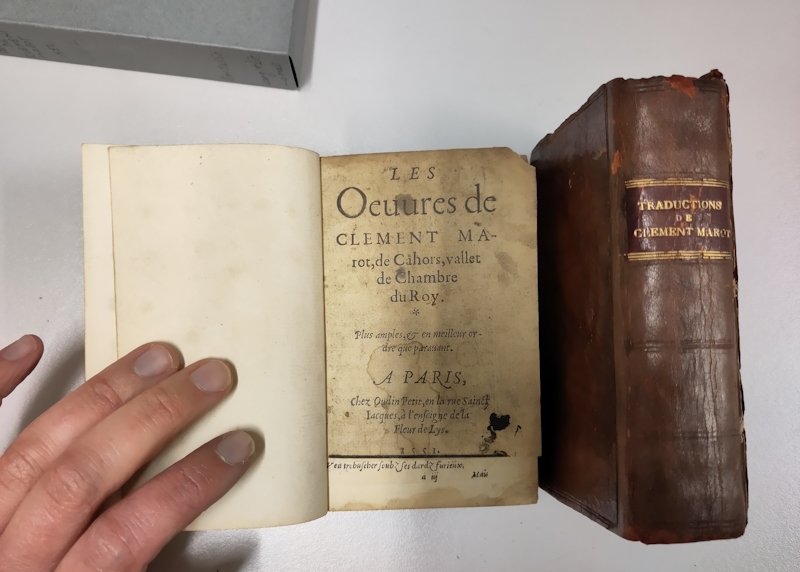

My first visit was to the shelf of 61 books with the classmark suffix ‘small’. They range from a rare 1551 anthology of French poet Clément Marot to the equally rare 1924 anthology of poems by physicist Edward Neville da Costa Andrade FRS, with the rejected long title of Stone fruit for sound stomachs. Grown by ... a poet of London or if that be denied a natural philosopher or if that be not allowed yet (almost as rare a title) one who earns his living honestly. (offered with) Airs (for the hautbois and other instruments).

The ‘literature’ portion of the classmark runs well into the twentieth century. Examples that caught my eye include a 1911 edition of Cast up by the sea: a boy’s story, the fictionalised colonial adventures of Sir Samuel White Baker FRS, and (riding a similar wave) the nautical novels of Captain Frederick Marryat FRS, including The little savage and Snarleyyow, subject of a previous post on this blog.

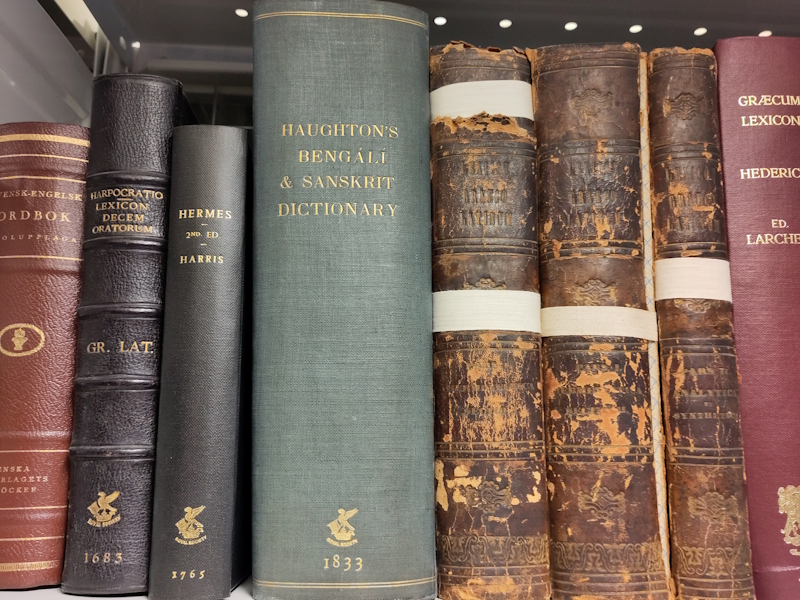

The poems and colonial adventure novels are exceptions, however. As I suspected, the majority of the volumes consist of pocket dictionaries, grammars and lexicons which would allow you to master dead languages, endangered ones, and international ones.

Similarly, the ‘large’ section consists mainly of thesauri and dictionaries, and includes the earliest volume of the ‘Lang.& Lit.’ classmark: a 1548 Basel edition of the thesaurus of Cicero’s work by humanist Marius Nizolius, which was meant to contain all acceptable words to be used by Latin purists. The oldest volumes were mainly donated as part of the foundational Norfolk Library, with a few given by individual Fellows or would-be Fellows following a Grand Tour. The dictionaries are fascinating in that they represent shifting geographies of people, languages and ideas, and they merit a detailed study.

I’ll leave you with my two favourite discoveries, which are examples of some of the earliest printed books in their respective languages.

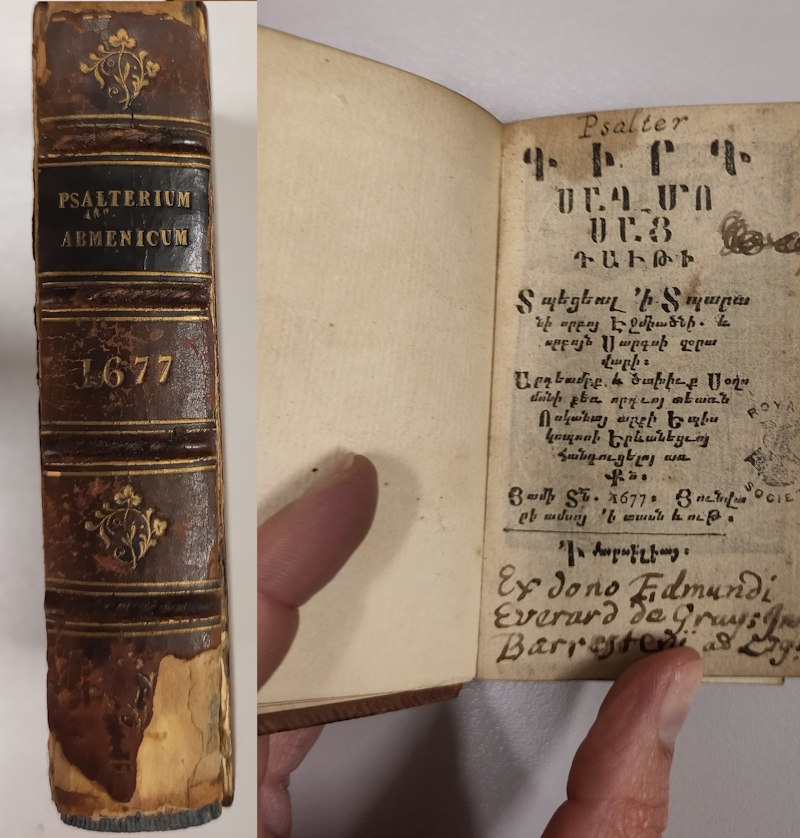

The first is a diminutive 1677 portable psalter in Armenian, printed on the press set up by Voskan Yerevantsi (ÕˆÕ½Õ¯Õ¡Õ¶ ÔµÖ€Õ¥Ö‚Õ¡Õ¶ÖÕ«, 1614-1674) in Marseille. Our copy was donated by a ‘Edmund Everard, Barrister at Gray’s Inn’, likely related to the Everard Baronets of County Tipperary in Ireland.

Yerevantsi was a pioneer of Armenian printing, who had published the first complete Bible in Armenian on his Amsterdam press in 1666, before moving to the newly-established Armenian quarter of Marseille in 1673 and opening the printing house where our copy of the Book of Psalms was produced. His cousin Soghomon Levonyan (ÕÕ¸Õ²Õ¸Õ´Õ¸Õ¶ Ô¼Ö‡Õ¸Õ¶ÕµÕ¡Õ¶, 1620-1680) took over the business on Yerevantsi’s death the following year. Interestingly, before printing the portable psalter in our collection, Levonyan published the first mathematical book in Armenian in 1675, a practical volume of arithmetic with useful unit conversion tables designed for Armenian merchants.

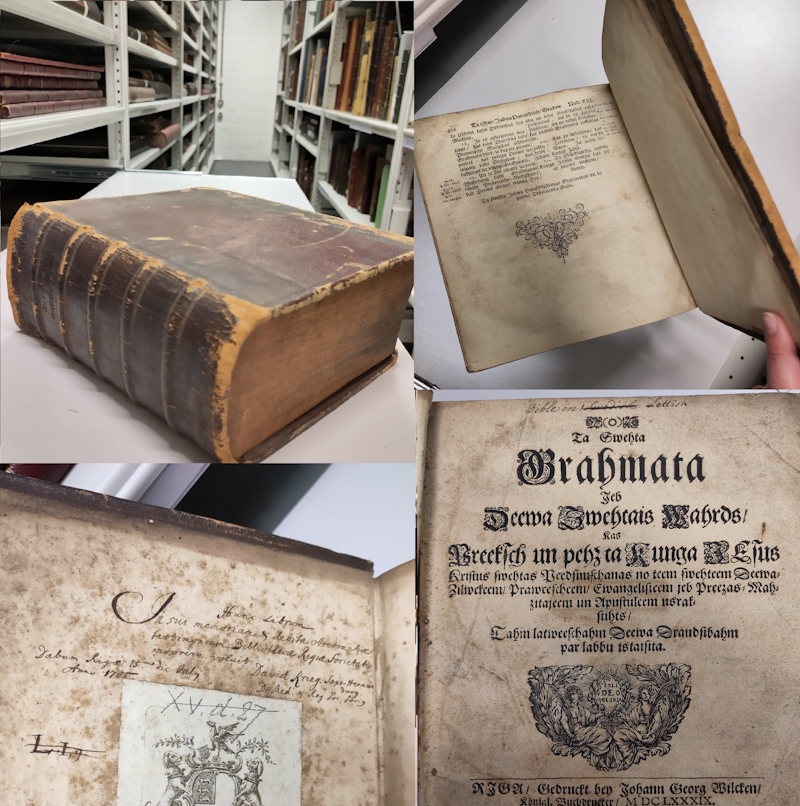

Finally, we have a large Bible printed in 1689, the first edition of the Old Testament translated into Latvian, then known as Lettish, by Johann Ernst Glück (1654-1705).

Our copy was donated by David Krieg FRS (1669-1710), physician in Riga, whose album amicorum is in Hans Sloane’s papers at the British Library. This book, in this translation, is a key monument for Latvian history as it remained the longest text in the language for several centuries. It codified the language and encouraged literacy, as well as serving as the basis for Protestant proselytism.

These two examples, and their importance in the history of their respective languages, show how amazing this little corner of our collections is. It’s tantalising that its richness is largely, if not completely, untapped.

Top image: title page of 'Rainy days in a library' by Herbert Maxwell, 1896 (detail)