Some prints in the Royal Society's picture collection - and even one of the oil paintings - are not who we thought they were, as Ainsley Vinall explains.

As part of a wider project to digitise our collection of prints and photographs, I’ve been writing descriptions for some of our printed portraits and making their images available on our Picture Library. Our secondary portrait collection documents the history of the Fellowship and includes over 1,000 engravings, etchings and lithographs as well as almost 6,000 photographs.

Many of the prints were donated by Fellows or their descendants, while others were given by members of the public or purchased specifically to fill gaps in the collection. Some prints have been with the Royal Society for so long that we don’t know exactly when they were acquired. Almost all the works in our printed collection show past Fellows or other distinguished scientists. However, through this process I have identified a few cuckoos: prints acquired as an image of a Fellow which actually show someone else.

Most of these erroneous acquisitions would have been easy mistakes to make. A lithograph in our collection simply titled ‘Helvétius’ was understandably thought to portray the French physician Jean Claude Adrien Helvétius FRS (1685-1755), but actually shows his son, Claude-Adrien Helvétius (1715-1771), who was not a Fellow. Another example is our mezzotint, supposedly of the philosopher and psychologist David Hartley FRS (1705-1757), which is in fact a likeness of his less famous son, another David Hartley (1732-1813).

(L) Claude Adrien Helvétius, lithograph by François-Séraphin Delpech, c.1800 (IM/002030); (R) David Hartley, engraved by James Walker, c.1785 (IM/001967)

(L) Claude Adrien Helvétius, lithograph by François-Séraphin Delpech, c.1800 (IM/002030); (R) David Hartley, engraved by James Walker, c.1785 (IM/001967)

As well as accidentally collecting images of Fellows’ sons, we also have a few of their fathers. Our portrait of ‘Benjamin Hoadly’ shows the bishop of that name (1676-1761), rather than his physician son Benjamin Hoadly FRS (1706-1757). Similarly, our mezzotint engraving of non-Fellow John Hobart, 1st Earl of Buckinghamshire (1693-1756) was previously thought to show his son, John Hobart FRS, 2nd Earl of Buckinghamshire (1723-1793). And yes, as you’ve probably spotted by now, I’ve recently been working through ‘H’ in the alphabetical sequence!

When these prints were acquired, it would have been very hard to verify the identity of the sitters. The names and descriptions on the objects themselves could easily have referred to the Fellows they were thought to show. Thanks to the work of archivists at institutions all over the world, modern authority databases make it relatively easy to identify when certain artists were active and to match these dates with the approximates ages of sitters.

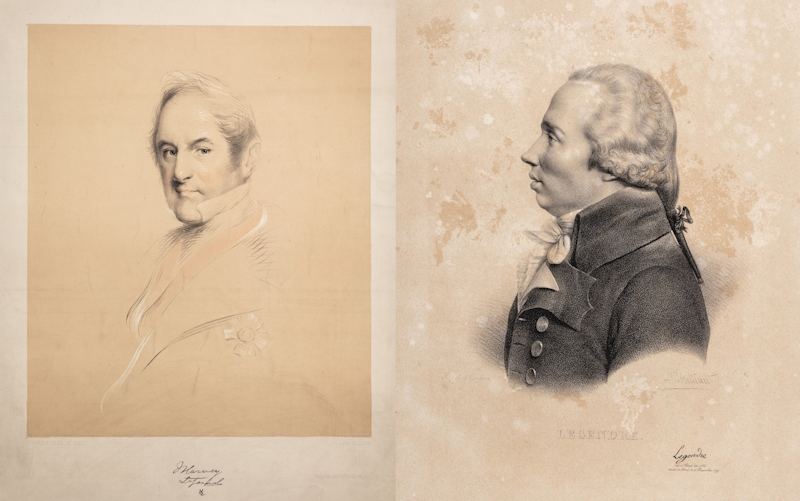

Some of the more interesting cases of mistaken identity are the ones where the real subjects are totally unrelated to the people they were originally thought to show. A lithograph in our collection catalogued until recently as a portrait of banker and Fellow Sir Robert John Harvey FRS (1785-1860), is actually an image of Sir John Harvey (1778-1852), a military officer who served as Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, Canada.

A more well-known example is the portrait of French politician Louis Legendre (1752-1797) which we had catalogued as the mathematician Adrien Marie Le Gendre (1752-1833), elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1789. Somehow the same portrait had been used in numerous publications to represent both men until two students at the University of Strasbourg uncovered the error, prompting institutions to update their records.

(L) Sir John Harvey, lithograph by James Henry Lynch, c.1850 (IM/001976); (R) Louis Legendre, lithograph by François-Séraphin Delpech, 1797 (IM/002699)

(L) Sir John Harvey, lithograph by James Henry Lynch, c.1850 (IM/001976); (R) Louis Legendre, lithograph by François-Séraphin Delpech, 1797 (IM/002699)

Intrigued by all these cases of mistaken identity, I also decided to take a quick audit of our painted portraits, just in case any were not who they should be. And as it turned out, there is a painting in our collection that has been falsely masquerading as a Fellow!

Peter Ball, painted by John Riley, 1671 (P/0149)

Peter Ball, painted by John Riley, 1671 (P/0149)

The portrait above, previously thought to be of the seventeenth-century physician and Original Fellow of the Royal Society Peter Ball FRS (c.1638-1675), contains a Latin inscription that reads ‘Petrus Balle miles/Aetatis 74/1671’ [Peter Ball knight/Aged 74/1671]. There are a number of inconsistencies with this: firstly Ball was never made a knight, but more obviously he was around 33 in 1671 and died long before he would have been 74. Confirming the inscription, the sitter is shown with grey hair and wizened eyes, visibly looking much closer to 70 than 30.

The portrait was purchased by the Royal Society in November 1993 from the ‘British Paintings 1500-1850’ auction at Sotheby’s, where it was listed as a painting of the physician by English portraitist John Riley (1646-1691). The painting previously appeared, again identified as Peter Ball FRS, in Portraits in Norfolk Houses, Vol 2 (1928) by Frederick Duleep Singh. Here it was shown to be in Raynham Hall until 1904, when it was then sold by John Townshend, 6th Marquess Townshend.

Snippet from pages 198-199 of Portraits in Norfolk Houses, Vol 2, Frederick Duleep Singh, 1928. Public domain, via Archive.org

Snippet from pages 198-199 of Portraits in Norfolk Houses, Vol 2, Frederick Duleep Singh, 1928. Public domain, via Archive.org

However, the father of Peter Ball FRS, Sir Peter Ball, was baptised in 1598 which would have made him 73 or 74 in 1671. The elder Peter sat in the House of Commons and later acted as attorney-general to the Queen, Henrietta Maria of France, a service for which he was knighted in October 1643. These facts make it clear that our portrait, which has been identified as Peter Ball FRS for at least a century, is actually a painting of his father, Sir Peter.

Sir Peter Ball was not a Fellow or a natural philosopher, but as the father of two of the earliest recruits to the Royal Society – Peter Ball and his older brother, the astronomer and Founder Fellow William Ball (c.1631-1690) – he’s certainly a figure well connected to the Society’s origins. The painter John Riley likely encountered Sir Peter at the court of Charles II, the Society’s Founder Patron, when Riley was at the beginning of his artistic career.

The painting of Sir Peter was made during his last five years in Parliament, where he acted as Recorder of Exeter. He was also the patriarch of a large family – William and Peter were respectively the eldest child and third eldest son of Sir Peter’s seventeen offspring. When William hosted a dinner in 1661 for Christiaan Huygens FRS (1629-1695), the Dutch mathematician sat down with a whole table of his host’s brothers and sisters. Unfortunately, there is no known portrait of William Ball and it seems we can no longer claim to have a painting of the younger Peter Ball either. However, as William also acted as the first Treasurer of the Royal Society, we do still hold the wrought iron chest he gave us in 1663 as a record of his dedication.