Virginia Mills tells the story of three telescope lenses linked to Christiaan and Constantijn Huygens, and now owned by the Royal Society.

The Royal Society owns three seventeenth-century telescope lenses linked to the Huygens brothers, Christiaan and Constantijn.

Dutchman Christiaan Huygens was an Original Fellow and active correspondent of the Royal Society. He made significant innovations in telescope design, building his own instruments and using them to make astronomical observations and discoveries, most famously Saturn’s moon Titan in 1655.

Christiaan was assisted by his older brother Constantijn Huygens Jr (not FRS). One of the Society’s three Huygens lenses was donated by them to the Society in 1691, while the other two were given by their original owners in the eighteenth century – the 170-foot focal length glass was the gift of Sir Isaac Newton. Analysis of inscriptions on each has revealed the signature of Constantijn, suggesting that he made the lenses, previously assumed to be the work of the more celebrated Christiaan.

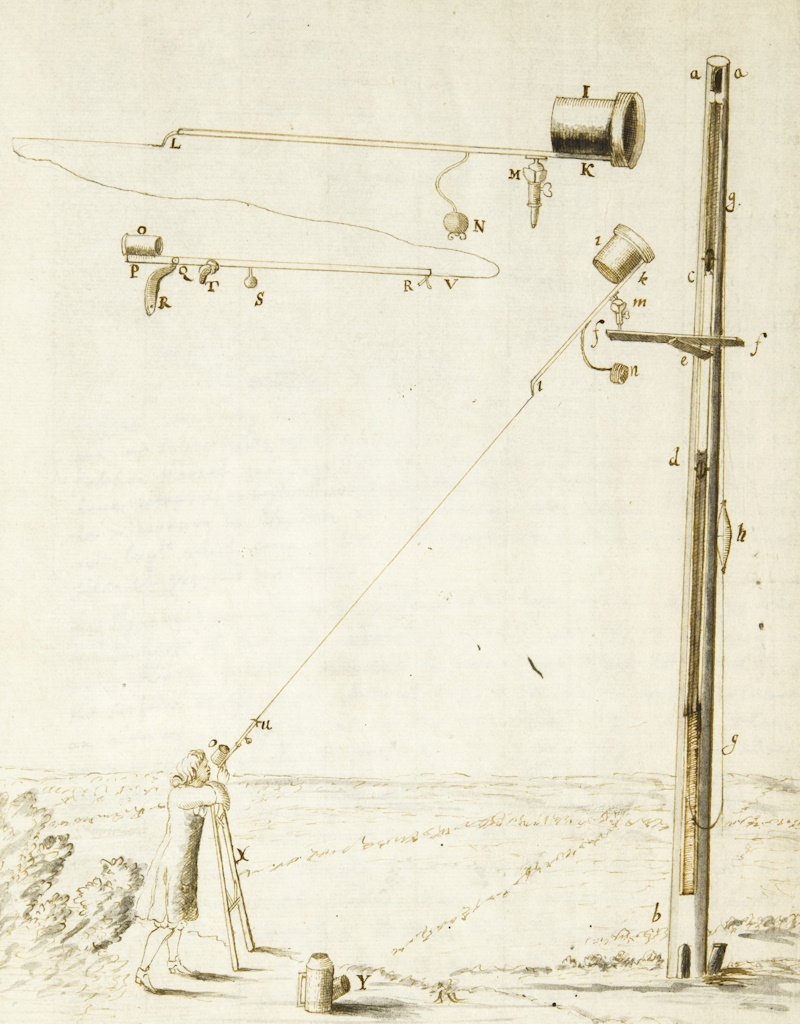

The object glasses were for use in an aerial telescope, as described by Christiaan Huygens in a 1684 article in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. As you can see below, this kind of telescope has no tube – instead, the object lens is mounted on a pole and attached to an eyepiece with a silk string to guide the sight:

Aerial telescope by Robert Hooke, with a 70-foot focal length affixed to a 50-foot pole, after a design and illustration by Christiaan Huygens in Astroscopia Compendiaria, 1684 (RS.15301)

Aerial telescope by Robert Hooke, with a 70-foot focal length affixed to a 50-foot pole, after a design and illustration by Christiaan Huygens in Astroscopia Compendiaria, 1684 (RS.15301)

The aerial telescope was an attempt to make longer focal lengths a practical proposition. Before the use of ‘Newtonian’ reflecting telescopes, refracting instruments required longer focal lengths to achieve powerful magnification while minimising chromatic aberration. The largest Huygens lens at the Society has a focal length of 210 feet (64m), three times that of the one by Robert Hooke (above), while the others have still unwieldy-sounding focal lengths of 170 feet (51.8m) and 122 feet (37.2m) – the picture at the top of this article is of the 122-foot lens.

Each of the lenses has its own mahogany case, the legacy of the Victorian astronomer Warren de la Rue, who remounted the lenses in metal supports. We also possess an iron cylinder with wooden spar for housing the lenses while in use, an original ‘gunsight’ eyepiece, and other paraphernalia. Once assembled, the full telescope dispensed with the ‘heaviness and disproportion of the tube’, in the words of Christiaan Huygens. This flexibility, plus their impressive magnification power by contemporary standards, were presumably why the Royal Society proposed so many uses for the lenses.

The Monument to the Great Fire of London (Eluveitie, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The Monument to the Great Fire of London (Eluveitie, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

When the Society’s Council was searching for a site for a zenith telescope, after the Monument was found to be unsuitable (traffic disturbance was apparently an issue even in seventeenth-century London), St Paul’s Cathedral – another of Hooke and Wren’s architectural projects – was suggested. The lens to be tried was the Huygens one of 122-foot focal length, recently donated by the brothers, the first and smallest of the three to come into the Society’s possession. Unbelievably, even a cavernous cathedral was not large enough to accommodate such a telescope, but the Fellows weren’t done trying.

William Derham borrowed the same 122-foot lens a couple of times, but could not afford a pole to mount it on. It passed more profitably into the hands of James Bradley, Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, whose uncle and teacher James Pound co-opted a maypole from the Strand to mount it at his home in Wanstead, where he and Bradley observed the planet Saturn. In 1748 Royal Society President Martin Folkes took the lens to the observatory of the Earl of Macclesfield at Shirburn Castle, where a clear view of Jupiter was obtained.

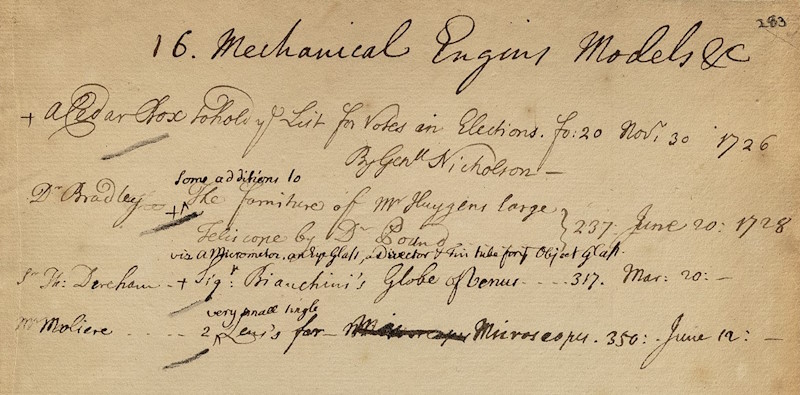

Record of James Bradley returning the 122-foot Huygens lens, 1728 (MS/416)

Record of James Bradley returning the 122-foot Huygens lens, 1728 (MS/416)

Henry Cavendish kept all three lenses from 1785 to 1787 and mounted them on a ship’s mast at his estate. He also set up a trial on Clapham Common comparing these old giants, the tools of his scientific ancestors, with the latest the eighteenth century had to offer by way of triple lens achromatic refractors a fraction of the size. The Huygens lenses were found to be of comparable quality, though not convenience, and this seems to be the last time they were successfully used for observation.

However, in the 1850s they were almost brought into service again, when astronomer Otto Struve attempted to determine whether there had been any changes in the rings of Saturn since the observations of Bradley and Pound over a century earlier. The key to making meaningful comparisons lay in eliminating variations due to different instrument design, so the fact that the 122-foot lens used by Bradley in the 1720s had survived was significant. It meant that Struve might be able to account for factors that influenced the earlier data: the constant of irradiation of the lens could be measured, for example (CMP/2/87).

Council also gave permission for the lens to be remounted, giving Struve the opportunity to repeat the measurements with a recreation of the original aerial telescope (CMP/2/97), thereby eliminating the instrumentation as a variable. Like earlier schemes to deploy the Huygens lenses, however, this ran into some logistical difficulties.

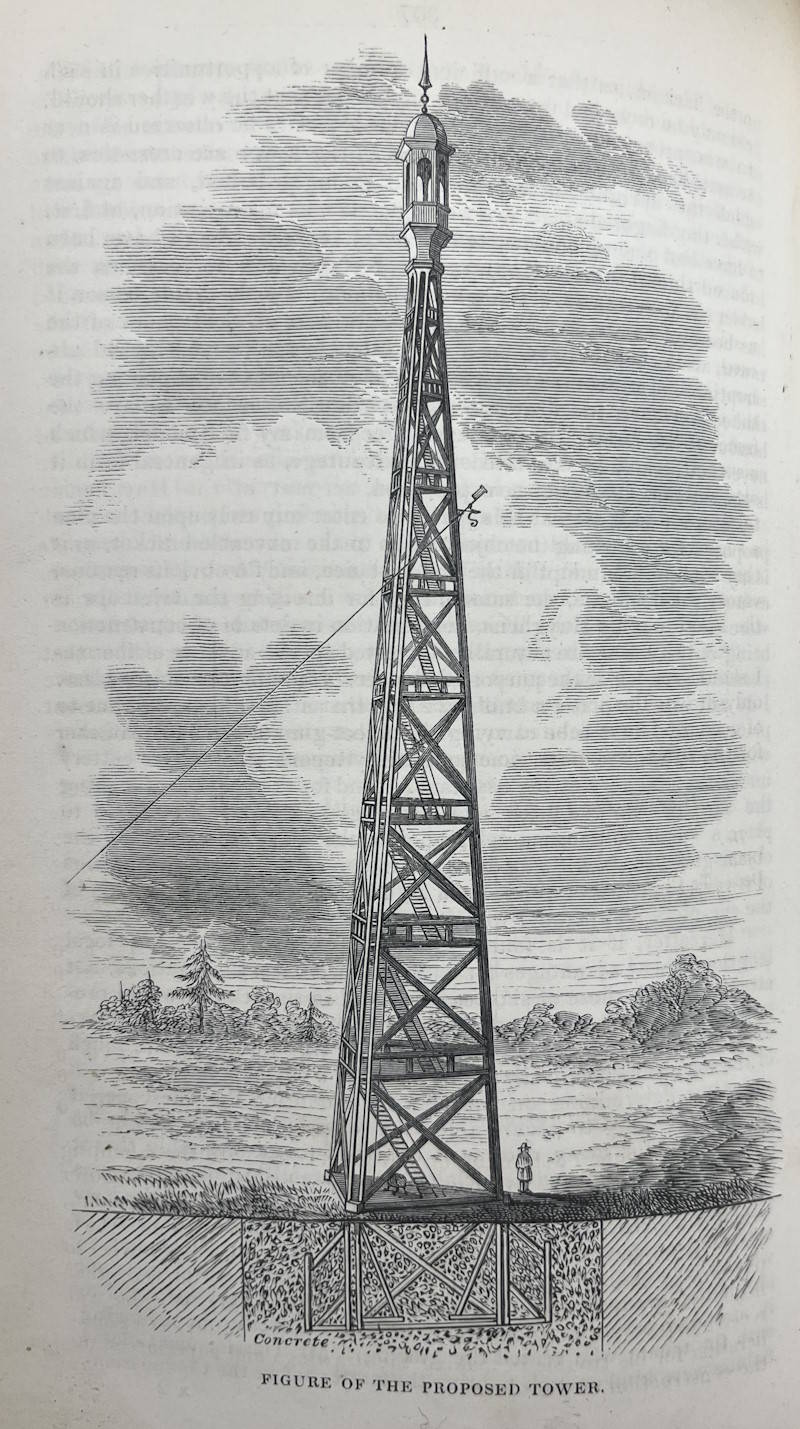

It was suggested that the Great Pagoda in the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, close to the Kew Observatory, was a suitable tower to mount the telescope. However, this was found to be surrounded by too many trees (!), the cutting down of which ‘in a public garden … was not warranted’. Warren de la Rue then drew up a detailed plan to build a new tower in the neighbouring Old Deer Park, but this proved to be too expensive.

Illustration of the tower proposed to mount the 122-foot Huygens lens in Old Deer Park, from a report by Warren de la Rue, 1855 (CMP/2/120)

Illustration of the tower proposed to mount the 122-foot Huygens lens in Old Deer Park, from a report by Warren de la Rue, 1855 (CMP/2/120)

In the judgement of Sir John Herschel, the recreation of the setup would need to be incredibly precise to render useful comparative results, so even with the original lens the data might not be considered positive evidence of any change in Saturn’s rings over the years. The chances of getting any useful data were deemed ‘out of proportion with the likely financial outlay’ (CMP/2/121), and although a committee was set up to investigate ways forward and some funds were given by the Society, they were later returned.

While nothing eventually came of this proposal – other than the new metal ring fittings added by Warren de la Rue, as noted in an inscription on the mount of the 122-foot lens (above) – the fact that the Huygens lenses are still in the Royal Society’s collections suggests that they were retained as working instrument components, at least in theory. They survived the 1781 transfer that saw most of the Society’s ‘Repository’ collection of curiosities and specimens go to the fledgling British Museum, and now function as display objects themselves, exciting the interest of present-day historians of astronomy visiting Carlton House Terrace.