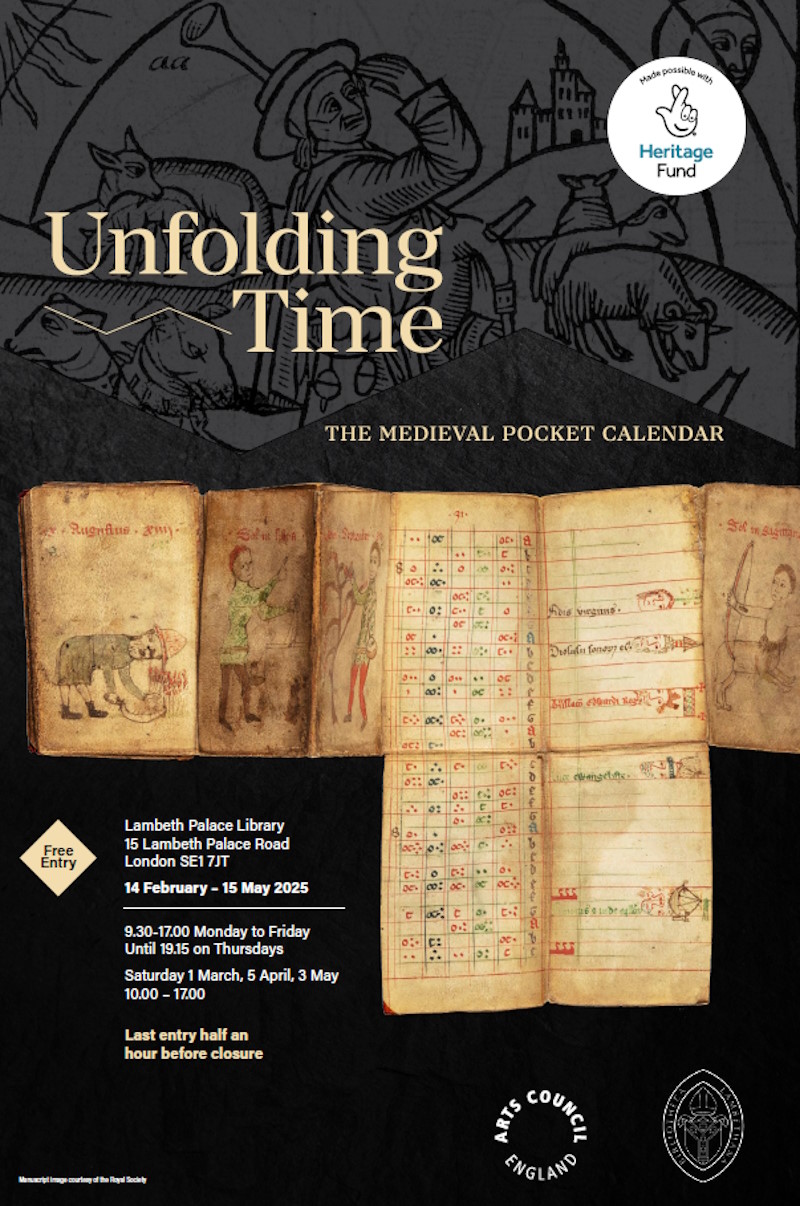

An exhibition at Lambeth Palace Library brings together some rare medieval concertina-fold almanacs, including one from the collections of the Royal Society, as Virginia Mills reports.

In London we’re feeling the seasons turning. Spring has arrived heralded by warmer weather, the changing of the clocks means lighter evenings, and in the parks the trees and tulips are blossoming and there are the first signs of bluebells.

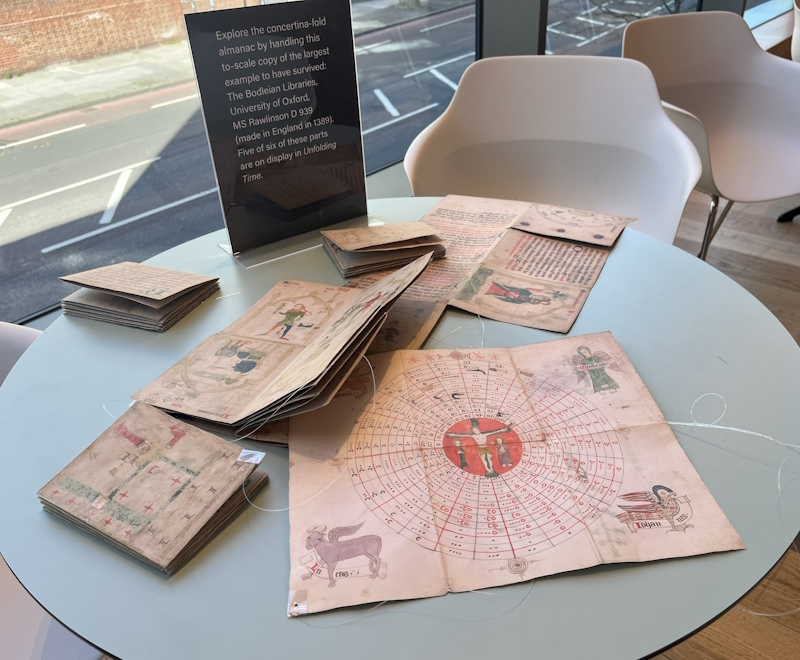

The way in which our medieval ancestors codified the passage of time is the theme of a fascinating event, ‘Unfolding Time’, currently on at Lambeth Palace Library. This is the first exhibition to bring together many of the known surviving medieval concertina-fold almanacs. You can find out exactly what these are in Lambeth’s helpful video (below), or better still by going to see the exhibition, which is free and runs until 15 May.

One of these unusual objects (MS/45) is on loan to the exhibition from the Royal Society. We’ve blogged about it before, and you can take a detailed look at all the different parts of this ‘very curious almanack’ on our Google Arts & Culture exhibit and Picture Library.

One of the things that makes this manuscript a favourite of mine is the density of information packed into such a small area, at least at first glance. New details are revealed as the parchment is unfolded, with readily decipherable images and some information that is encoded or baffling to the modern eye.

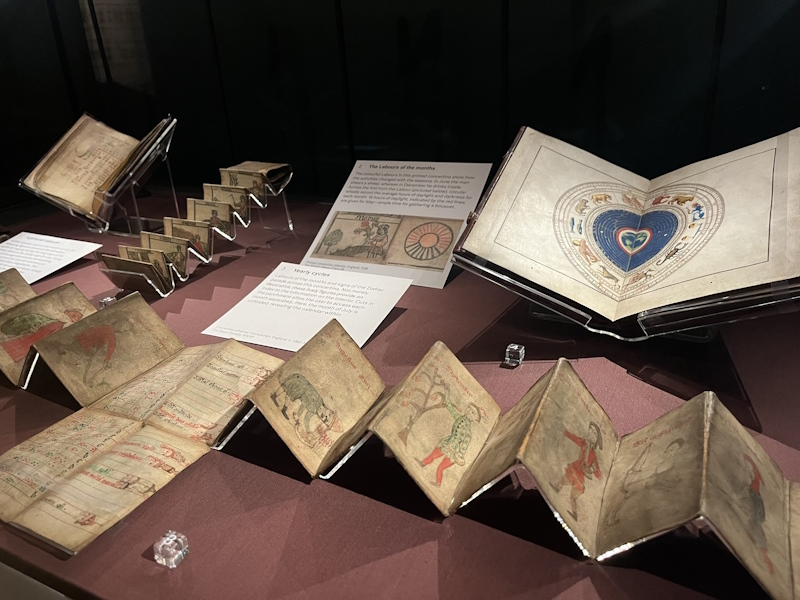

Royal Society MS/45 on display as part of the ‘Unfolding Time’ exhibition at Lambeth Palace Library, alongside almanacs from the British Library and Lambeth Palace Library

Royal Society MS/45 on display as part of the ‘Unfolding Time’ exhibition at Lambeth Palace Library, alongside almanacs from the British Library and Lambeth Palace Library

Opening the manuscript lengthwise across the full year reveals brightly coloured signs of the zodiac and illustrations of the labours that typify each month. While your modern-day April activities might include spring cleaning, bringing out lighter summer clothing from storage, or reviewing your finances at the end of the tax year, the fourteenth-century advice from MS/45 suggests that April is the time for taking a break from the agrarian labours that occupy most of the medieval calendar. Mr April c.1383 can be seen carrying greenery in both hands, so maybe he’s ‘picking branches’, a springtime courtship activity where fresh spring foliage is gifted to your paramour. Or, as he’s alone, he might be engaged in a longer pilgrimage, returning from the Holy Land with the customary palm leaves to commemorate the journey.

April labour, Royal Society MS/45

April labour, Royal Society MS/45

April, of course, can be of religious significance in the Christian calendar as Easter often falls in this month. But not always – Easter Sunday is a moveable feast, marked the weekend after the first full moon following the spring equinox. One of the things I’ve learned from the exhibition is that concertina almanacs almost always feature a perpetual calendar which provides information on the phases of the Moon, allowing calculation of the date of Easter. Flipping over MS/45 does indeed reveal a perpetual calendar, which also includes a guide to the times of sunrise and sunset and the hours of daylight, from the days when the Sun was truly the clock by which life was regulated.

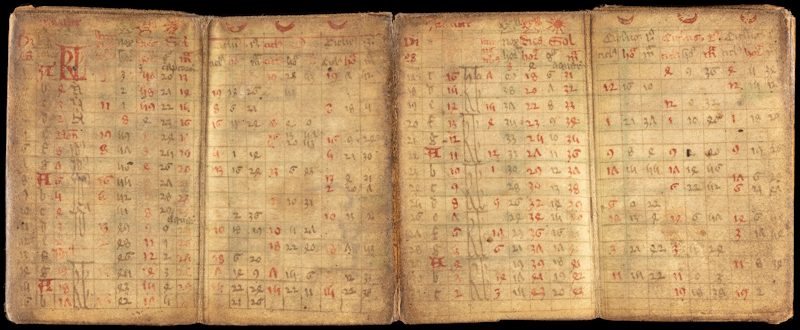

Perpetual calendar with astronomical data for January, Royal Society MS/45

Perpetual calendar with astronomical data for January, Royal Society MS/45

Half the year’s perpetual calendar is missing from MS/45 (well, it is over 600 years old and was already over 250 when it was given to the Royal Society). Every surface of these almanacs was always utilised to maximise the information you could carry on your belt or in your pocket – so what might the lost part of the almanac, on the other side of the six missing ‘perpetual calendar’ months, have contained? Seeing so many examples of these almanacs together at the Lambeth Palace Library exhibition provides some possible suggestions: perhaps an all-encompassing historical chronicle, starting with Adam and Eve? These are found in many of the exhibited almanacs, including a beautiful gold-illuminated example from the British Library.

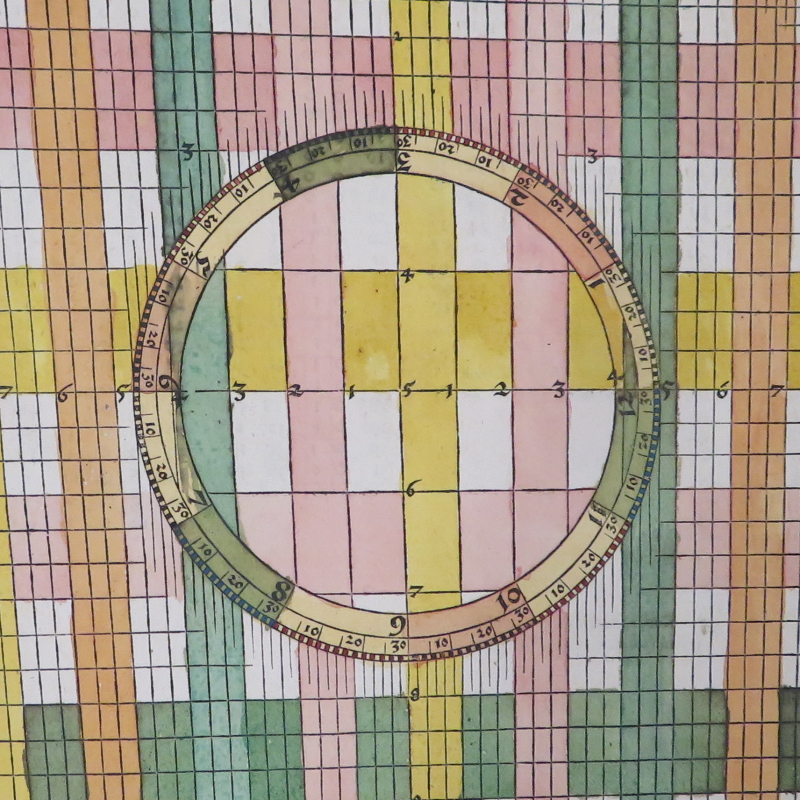

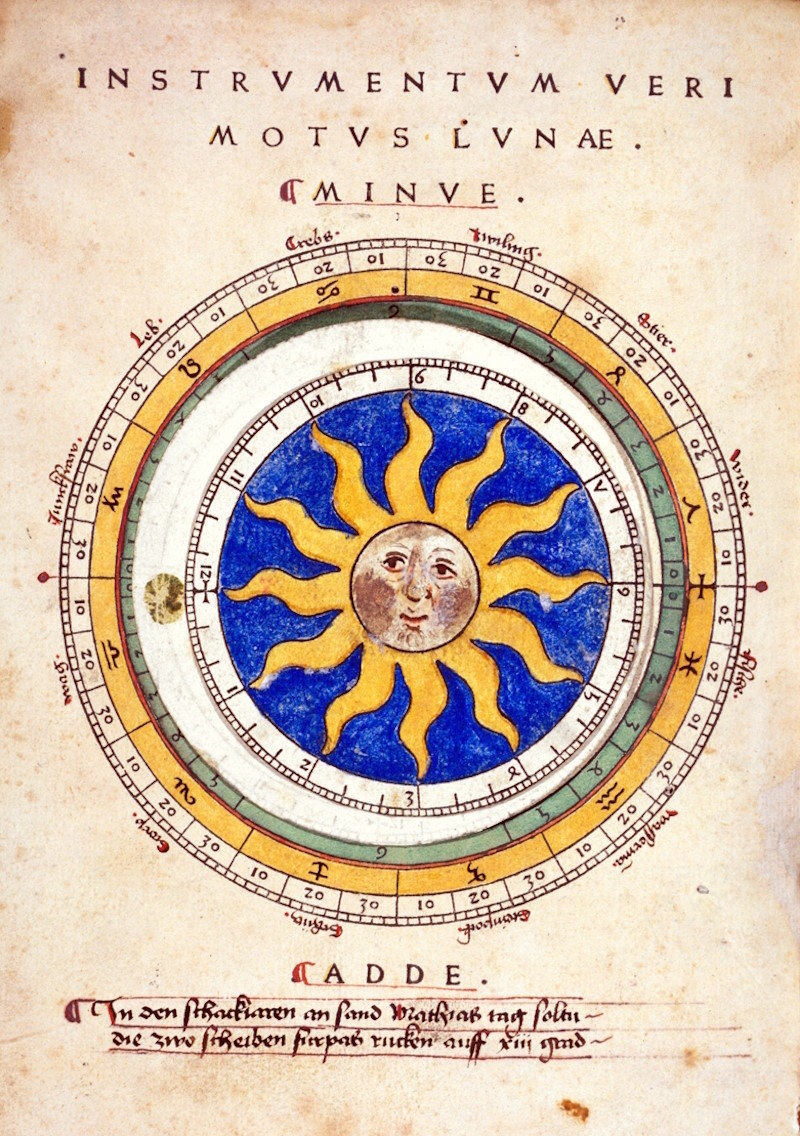

Volvelle from a 1474 printed almanac by Johannes Mueller (Regiomontanus), Royal Society Library R61028

Volvelle from a 1474 printed almanac by Johannes Mueller (Regiomontanus), Royal Society Library R61028

Or maybe a moveable instrument? One of my favourite features in the exhibition, from a Lambeth Palace Library codex dating from 1460, is a volvelle: a series of moving discs that chart the relative position of the Sun and Moon. This reminded me of a calendar for tracking the movement of the Moon in the Royal Society’s copy of a 1474 almanac by German astronomer Regiomontanus (above). Some of the almanacs even give medical advice or claim to predict the future: which years your bees might die, or when the weather might be particularly wet…

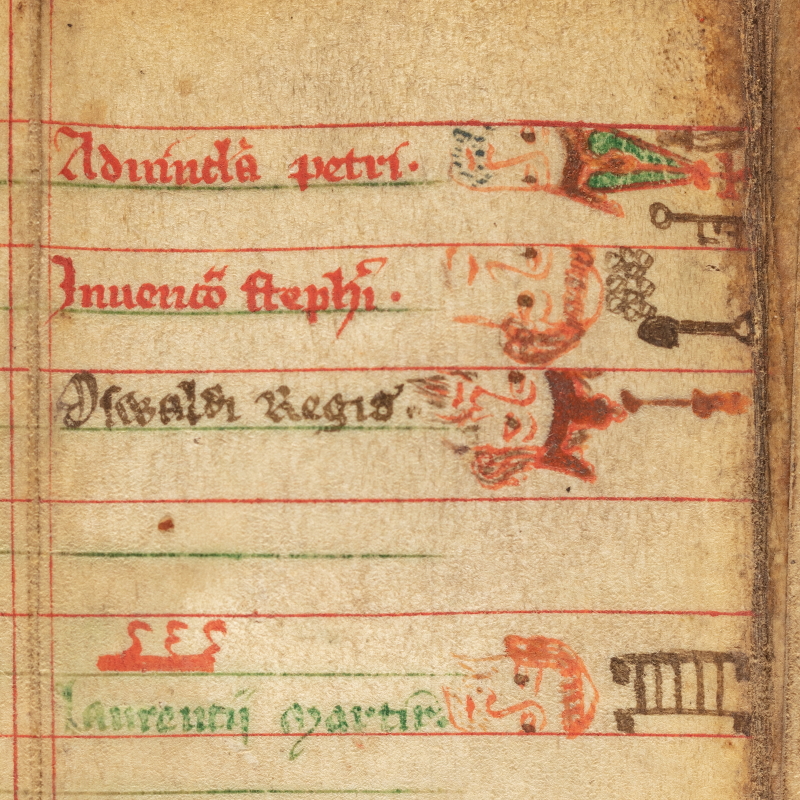

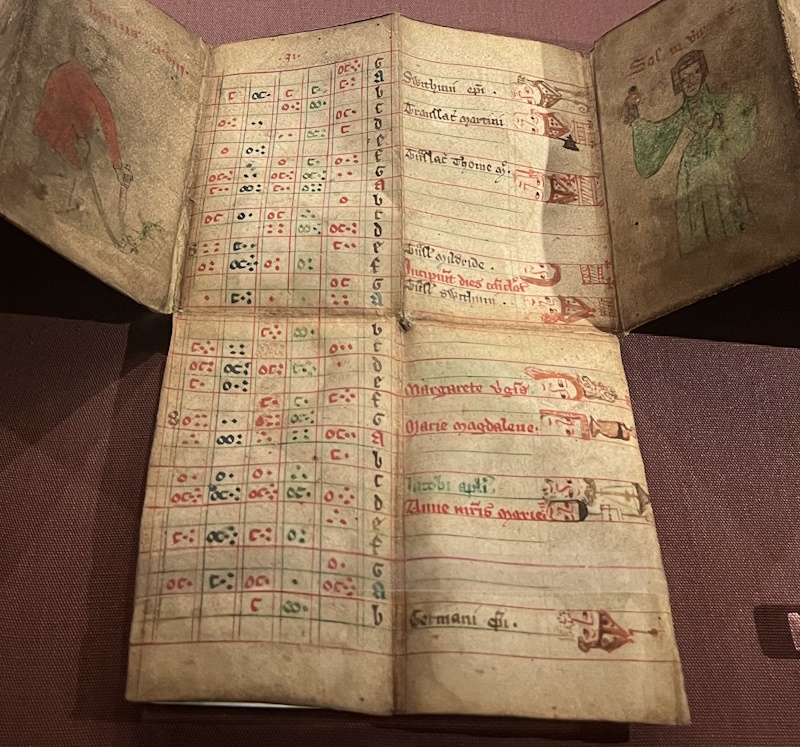

Liturgical calendar for July, marking holy days including the feast of Saint Margaret (sixth face from top). Royal Society MS/45

Liturgical calendar for July, marking holy days including the feast of Saint Margaret (sixth face from top). Royal Society MS/45

The final unfolding of MS/45 reveals a liturgical calendar on its inner compartments. Here fixed saints’ days in the devotional calendar are marked with portraits of the saints and their emblems. July (above), one of my personal favourites, shows Saint Margaret surmounted by the head of a dragon, seen side on, a reference to her supposedly having been swallowed by the devil disguised as a dragon before her eventual martyrdom by beheading. This grisly tale features elsewhere in the exhibition too.

I was also fascinated to see some examples of leather pouches used to store and carry these ‘mini reference libraries’. All in all, I highly recommend going to discover ‘Unfolding Time’ for yourself at Lambeth Palace Library until 15 May. You can even get hands-on with some facsimiles!