While cataloguing letters sent to physicist Joseph Larmor, Ana Brown finds Charles Chree, Superintendent of Kew Observatory, in a spot of bother at the office.

As an archive cataloguer, I have the privilege of working on a huge variety of topics, many of which are new to me. This has certainly been the case while I’ve been cataloguing a collection of letters sent to physicist Joseph Larmor between 1881 and 1939.

The correspondence from British physicist Charles Chree particularly piqued my interest. Chree was writing from his position as the longest-serving Superintendent of Kew Observatory, a post which he held for 32 years between 1893 and 1925. That’s a long time to squeeze into one blogpost, so I’ll be focusing on the small windows into his experiences as Superintendent that he shared with Larmor through these letters.

Charles Chree (IM/Maull/000842)

Charles Chree (IM/Maull/000842)

Kew Observatory, known since 1981 as the King’s Observatory (I’ll be sticking to Kew throughout as this is how Chree referred to it) is located in Richmond Park, Surrey, inside the Old Deer Park. It was commissioned in 1769 by King George III, motivated by his desire to observe the transit of Venus across the Sun in June of that year. Managers of Kew Observatory included the British Association for the Advancement of Science (now the British Science Association), and the Royal Society, who took charge of it in 1871 with the help of funding from merchant John Peter Gassiot. It’s now a private residence that hosts occasional public openings, such as the one my colleague Virginia Mills described in a previous blogpost.

At the time Chree became Superintendent, Kew Observatory functioned as the central observatory for the Meteorological Office and was also known for its prestigious role in checking the accuracy of scientific equipment and timepieces. From 1878 these were sent to the Observatory to be granted a ‘Kew Certificate’ of excellence. Instruments were sent from abroad too: I’ve been reading a book by Lee T Macdonald which notes that, in 1890, instruments came in from Hong Kong, Italy and Portugal, and by 1899 Chree’s eighteen staff were testing thousands of items per year, including thermometers, telescopes, watches, binoculars and barometers.

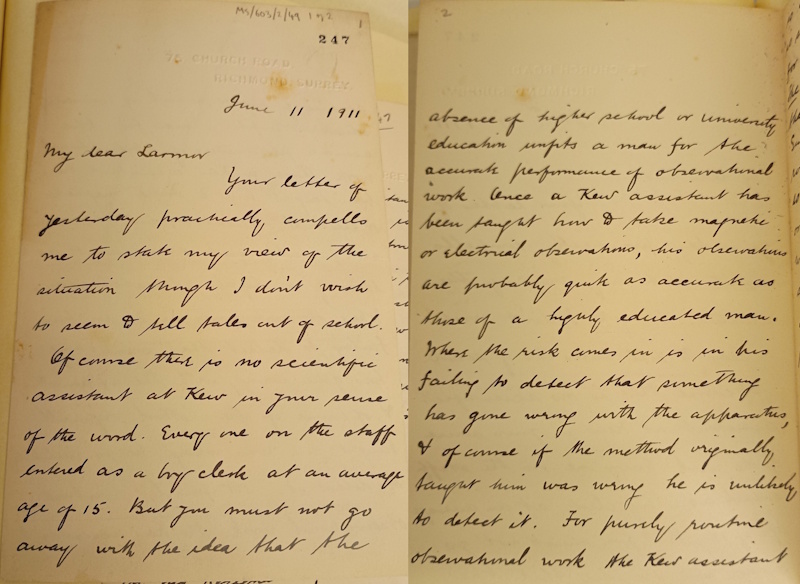

Work at Kew was supported by the ‘boy clerks’, young men aged 15-17 who were employed to do the more routine administrative and computing calculations. Chree praised the work of these boys, noting that:

‘You must not go away with the idea that the absence of higher school or university education unfits a man for the accurate performance of observational work. Once a Kew assistant has been taught how to take magnetic or electrical observations, his observations are probably quite as accurate as those of a highly educated man.’ (MS/603/2/49):

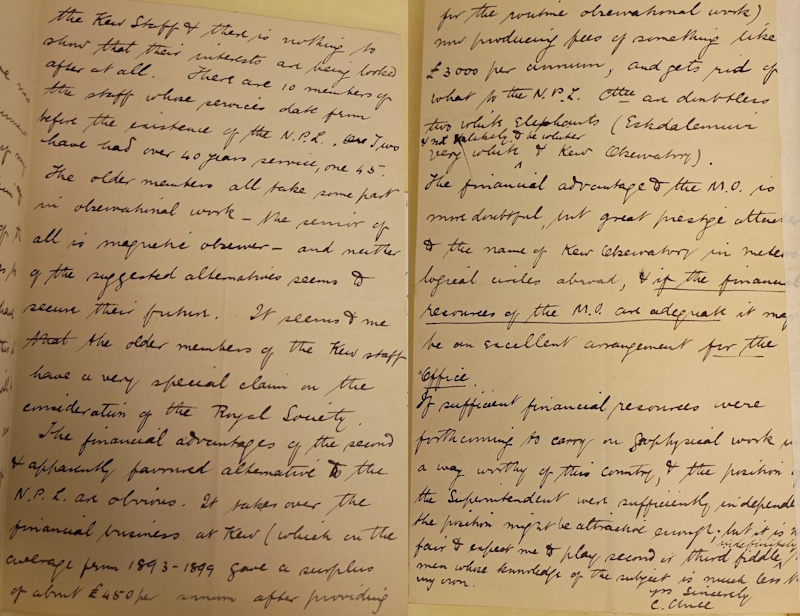

However, Chree, speaking in a private letter to Larmor dated 18 November 1909, also gave an idea of some of the difficulties and frustrations that the role of Superintendent entailed, particularly during times where the shape of the organisation was changing and responsibilities shifting. In 1908, the magnetic observations formerly carried out at the Observatory had been transferred to the new Eskdalemuir facility in Scotland, in response to challenges to the magnetic work at Kew from the new electric tramways built in the area.

Then, in late 1909, a joint committee of the Royal Society and the National Physical Laboratory (which had been established at the Observatory in 1900) negotiated to move the instrument standardisation work from Kew to Bushy House in Teddington, Middlesex, although the certificates for particular items such as barometers would still bear the subheading ‘Kew Certificate of Examination’. They also decided to hand over more responsibility to the Meteorological Office.

In his November letter, Chree noted his exclusion from the negotiations, writing ‘it is not fair to expect me to play second or third fiddle indefinitely to men whose knowledge of the subject is much less than my own’ (MS/603/2/43), as well as concerns over the staff at Kew, as he felt ‘there is nothing to show that their interests are being looked after at all’:

This was reiterated by Robert Harrison, who wrote to Larmor with his view that:

‘settling everything over [Chree’s] head seems to me to be treating a man of acknowledged scientific distinction as if he were not an intelligent being: and the process of handing him over, first from a position of practically independent authority into a subordinate position to the N.P.L. and now, as proposed in this printed scheme, under the control of another authority, does seem to be a humiliating way of treating such a man’ (MS/603/2/44):

The Larmor volumes (so far) unfortunately don’t give much of a conclusion to this, but I’m certainly keen to find out more. We do know that Chree stayed on as superintendent until 1925, so someone must have soothed his ruffled feathers! Whatever the conclusion, as an archive cataloguer this has been such a useful reminder of the value of letters in providing a more nuanced and personal look at the bigger picture – in this case the running of the Kew Observatory and the experiences of its Superintendent of 32 years. These perspectives will undoubtedly make further research all the more compelling.

Top image: Kew Observatory, AndyScott, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons