Jon Bushell reports on an unnerving medical incident during the Royal Society’s Halley Bay Antarctic expedition in 1957.

If I was making a list of the worst places in the world to get seriously injured, Antarctica would be quite near the top. Aside from the extreme cold, it’s also practically uninhabited and you’d be a very long way from the nearest A&E. Unfortunately, a serious injury is exactly what happened to Colonel Robert Arthur Smart, the leader of the Royal Society’s Halley Bay expedition in 1957. Worse still, he was the expedition’s Medical Officer.

Colonel Smart at the Royal Society, Burlington House, prior to his departure in 1956 (Royal Society archives)

Colonel Smart at the Royal Society, Burlington House, prior to his departure in 1956 (Royal Society archives)

We’ve blogged on Halley Bay before, so here’s a quick recap: the International Council of Scientific Unions arranged a global research effort known as the International Geophysical Year (IGY) from 1957 to 1958, to coincide with a period of maximum solar activity. The Royal Society’s contribution was an expedition to establish a research station in the Antarctic. An advance party was sent out in 1956 to set up the base, with the main group following in January 1957.

Robin Smart, as he was usually known, had studied medicine at Aberdeen University and joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1936. He had a particular interest in cold weather injuries and ailments, which made him an excellent fit for Halley Bay. He was offered the position of expedition leader in August 1956, and agreed to accept on the condition that he would only stay for a year, as he didn’t want to be away from his wife and young daughter for too long.

The main hut at the Halley Bay research base (Royal Society archives)

The main hut at the Halley Bay research base (Royal Society archives)

The duties expected of the expedition leader were wide-ranging. Smart would oversee management of the base, as well as all aspects of the scientific research to be conducted there. He was also the main point of communication with the outside world, providing regular cables to the Royal Society concerning the expedition’s research progress and general wellbeing. On top of everything else, he had his own investigations, which included a nutritional study of sledging rations at the request of the Medical Research Council, and ornithological studies of the emperor penguin population.

While out on one of his skiing excursions to see the penguins in mid-August 1957, Smart had a nasty fall, and the camera he was carrying was rammed into his abdomen. He was badly bruised, but he assured the rest of the expedition party that he just needed a few days’ rest. In fact, his injuries were more serious: a bruised liver and a damaged bile duct. Given his medical training, Smart must have suspected he was badly hurt, but was determined to tough it out, and after a few days in bed he was up and about again.

Penguins at Emperor Bay, west of the main base (Royal Society archives)

Penguins at Emperor Bay, west of the main base (Royal Society archives)

Over the next fortnight it became clear that his condition was worsening, and by early September he was bedbound again. Joe MacDowall, the expedition’s head meteorologist, assumed leadership duties, while also taking on the responsibility of nursing Smart, who was placed on a liquid diet and kept in a sitting position to help his bile secretions drain downwards. In MacDowell’s later account, On floating ice, he recalled how Smart instructed him to study the surgical procedure for draining an abdomen, in case it became necessary.

Smart’s health took a sudden turn for the worse on 16 September when he became very faint and his heart rate spiked. After a few minutes the symptoms subsided, but he had more attacks throughout the day which suggested something had ruptured internally. The expedition members, already worried about Smart’s condition, feared the worst. Word was quickly sent out to the other bases in Antarctica – the American party at Ellsworth Station offered to help, and the (Commonwealth) Trans-Antarctic Expedition (TAE) prepared to fly their doctor and medical supplies over from Shackleton Base.

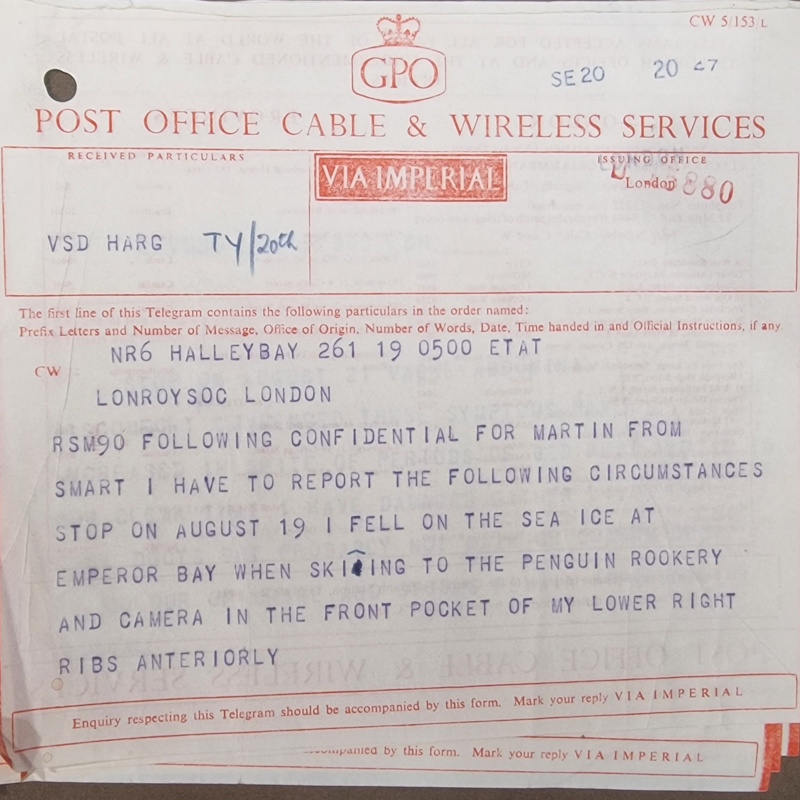

Thankfully, once the 16 September medical emergency had passed, Smart’s condition improved. By the 19th, though still in bed, he was able to carry out some light office duties and informed the Royal Society of all that had transpired. Despite being in regular telegram contact with the UK, Smart had not previously disclosed his fall or condition to the Society.

The first page of Smart’s cable to the Royal Society on 19 September 1957, describing his accident the previous month (EXP/11/1/1/221)

The first page of Smart’s cable to the Royal Society on 19 September 1957, describing his accident the previous month (EXP/11/1/1/221)

As soon as his message arrived at the Society, staff and Officers sprang into action. Medical advice was sought, to clarify Smart’s diagnosis and treatment options, and Smart’s wife was informed of the situation. The Society’s Assistant Secretary, David Christie Martin, managed a telephone call to the base around 8pm on 21 September. By this point Smart was well enough to get out of bed for brief periods and spoke to Martin on the call, which must have been a relief.

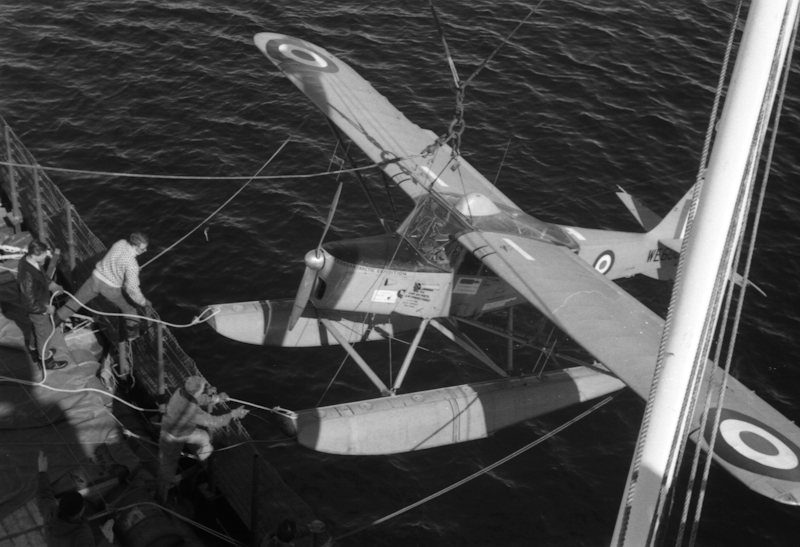

However, by 21 September new trouble was brewing. The relief plane from Shackleton base, the Auster, had taken off the day before but had flown too far north of Halley Bay. After landing to avoid running out of fuel, the two men on board became trapped in a blizzard for the following nine days. A second relief flight had to be sent out by TAE to recover them, so the doctor didn’t arrive at Halley Bay until 1 October. While his patient was already on the mend by this point, he did bring medicine to treat Smart’s thrombosis.

The TAE’s floatplane, the Auster being unloaded in December 1956 (RS.12089)

The TAE’s floatplane, the Auster being unloaded in December 1956 (RS.12089)

Smart went on to make a full recovery. He departed the Antarctic as planned in January 1958 when the annual supply ship arrived, with MacDowell taking over as expedition leader. After returning to England, Smart remained involved with the Antarctic Subcommittee of the British National Committee for the IGY, collating the research results coming through from Halley Bay and preparing them for publication. Smart was lucky to recover so well, particularly given his initial stubbornness following the accident. It just goes to show that doctors really do make the worst patients.