The Royal Society Library has acquired the scientific papers of David Jones, or 'Daedalus', whose research topics ranged from bicycle stability and the ‘burning mirrors’ of Archimedes to the arsenic in Napoleon's wallpaper.

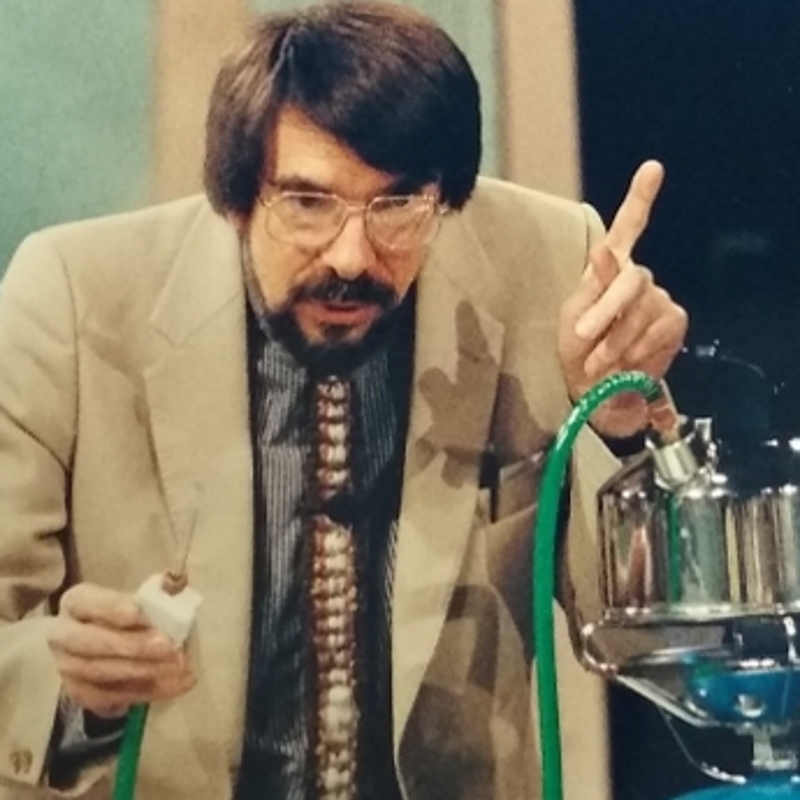

Since accessioning the collection of David E.H. Jones we have made no secret of our excitement. Jones’s fake (or is it?) perpetual motion machine was refurbished (thanks Nottingham University!) and displayed for all to see in our Marble Hall. A blogpost and a mini-exhibit quickly followed, further introducing the man behind the ‘motion’.

Display case in the Royal Society depicting some of David Jones’s research on bicycle stability and chemical gardens.

Anyone familiar with Jones’s work will understand our engagement with it. His really is the collection that keeps on giving. It includes scientific objects, photographic material and book illustrations, and spans topics from bicycle stability to the possibility of growing a ‘space garden’ in microgravity to the plausibility of the legend of the ‘burning mirrors’ of Archimedes. It is wonderfully eclectic, and cataloguing it has offered a fascinating insight into Jones’s truly unique approach to science.

An example of artwork from Jones’s first book The inventions of Daedalus: a compendium of plausible schemes (1982), depicting steam-powered boots to heat water underfoot, allowing people to walk safely to dry land.

One theme that runs consistently throughout the collection is Jones’s commitment to scientific demonstration and communication. Everything he created was intended for public consumption. His science writing as the fictitious inventor Daedalus blended humour with scientific thought in an attempt to engage as many readers as possible; his inventions, meanwhile, were intended for display, with his perpetual motion machines touring various cities and challenging viewers to guess how they worked.

Members of the public examining the perpetual motion machine in York, 1981, as part of a competition hosted by New Scientist.

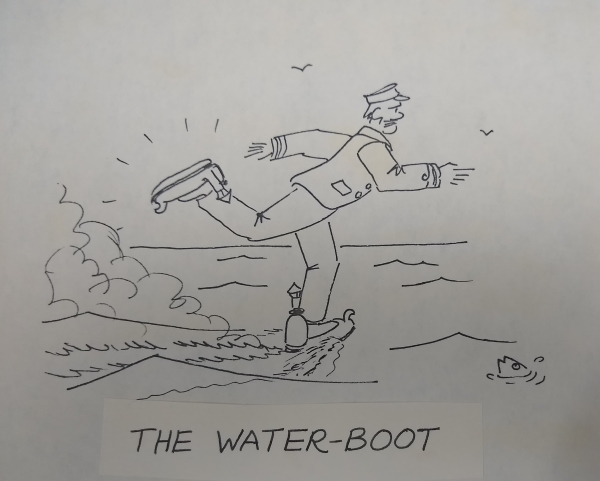

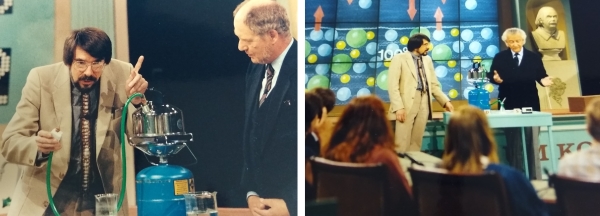

This commitment is also evident in Jones’s involvement in a variety of educational television and radio series. One of these was Don’t Ask Me, a 1970s Yorkshire Television production in which viewers were invited to send in scientific questions to be answered by researchers in front of an audience. In an article entitled The art of scientific demonstration (originally published in Proceedings of the Royal Institution, 1997) Jones noted that ‘seeing something you don’t understand doing something you don’t understand is not informative’. This leads us to Jones’s particular style of scientific demonstration, one which preferred everyday objects – saucepans, bottles, sandpaper, electric drills, golden syrup and so on – despite the experimental challenges they posed.

In one episode of Don’t Ask Me, when the discussion turned to the transmission of sound through liquids and solids, Jones improvised an underwater piano only audible when listeners submerged themselves in water. Similarly, when talking about the time-constant of viscous flow in liquids, Jones invited barefoot volunteers to run over a large tray of custard. At no point did Jones argue that the educational value of such demonstrations equalled that of a typically studious approach (‘there is no escaping the sad truth that students have to be studious’.) Rather, he was of the belief that they served another important purpose: making viewers feel more at ease and comfortable with science.

Jones (L in both images) on the German science television programme Kopf um Kopf (Head to Head).

Furthermore, in some cases the involvement of the audience opened doors to research that would not otherwise have been possible. In 1980 Jones hosted BBC Radio Four’s A Touch of the Vapours, where he asked if anyone knew the colour of the wallpaper in Napoleon’s room on the island of St Helena. He speculated that if this wallpaper was green, it is possible that Napoleon was accidentally poisoned by arsenical vapours from it, rather than dying from deliberate foul play. A listener wrote to the BBC with a sample of this wallpaper which had been preserved in a family scrapbook, and Jones set about analysing. The result was an article published in Nature where Jones concluded that, though it would not have been enough to kill Napoleon, there certainly was arsenic in his wallpaper and it likely contributed to his ill health prior to death.

David Jones’s contributions to television and radio provide a perfect example of what positive scientific communication can achieve. Regardless of how serious or light-hearted, thoughtful or funny it may be, the art of demonstration makes a subliminal point to the viewer, that science:

‘is concerned to ask questions about the whole perceptible world, to provide answers to them, and to make those answers publicly available. Further still, those answers should be verifiable by observation and demonstration.’ [Jones in The art of scientific demonstration]

As is indicated by our motto Nullius in verba (colloquially translated as ‘Take nobody’s word for it’) the Royal Society has always been grounded in this questioning, get-your-hands-dirty approach. While – as far as I know – there was no use of custard in the experiments of our earliest Fellows, they were wont to utilise powdered unicorn’s horn from time to time, and I think they would have been impressed by Jones’s seemingly never-ending stream of creativity.

Please note: though catalogued, Jones’s perpetual motion machine material is not open for public access and will remain closed until 2048. Until then, you’ll just have to work it out for yourselves!