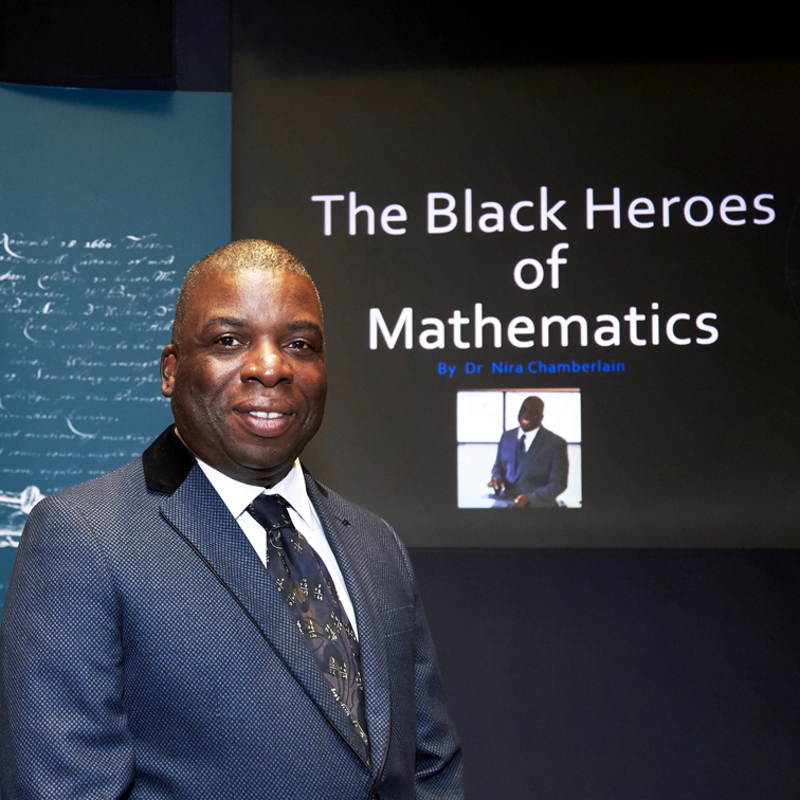

Dr Carolyn Roberts of Yale University, currently writing her first book 'To heal and to harm: medicine, knowledge, and power in the British slave trade', discusses some key documents in the Royal Society's archives.

In January 2013, while a doctoral student at Harvard University, I travelled to the UK to conduct dissertation research. As a historian of medicine and science studying slavery and the Atlantic slave trade, visiting the Royal Society was essential. Before my visit, I pored over Thomas Sprat’s first official history of the Royal Society, published in 1667.

According to Sprat (p.407), the Royal Society and the Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa (one of Britain’s early slave trading corporations) were ‘twin sisters’:

Both organizations were founded in 1660. Mark Govier’s research found that some Fellows of the Royal Society were also members of the Royal Adventurers, even serving in managerial roles. The pursuit of science and the slave trade supported one another. Scientists and slave traders worked together. These people and their histories were entangled.

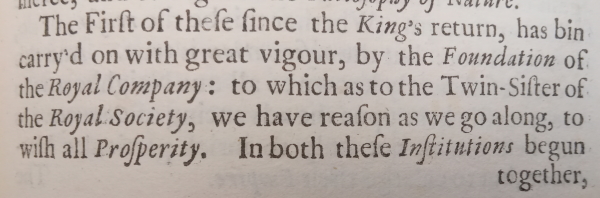

As I began to explore the Royal Society’s collections, I discovered a list of twenty-six questions that Secretary Henry Oldenburg sent to a ‘Mr Floyd,’ circa 1670:

CLP/19/55

Mr Floyd was the minister stationed at Cape Coast Castle in present-day Ghana. Cape Coast Castle functioned as Britain’s slave trading headquarters in West Africa. Beneath the chapel where Mr Floyd held services were vermin-ridden dungeons that held enslaved children, women, and men awaiting shipment to the Americas. From his administrative and ministerial perch, Mr Floyd was well-positioned to gather knowledge for the Society.

Oldenburg asked Mr Floyd about the ‘diseases ye Inhabitants are most subject to’ and the medicines they used. He also asked about the poisons and antidotes West Africans used, as well as the bark which kept their teeth so healthy and white.

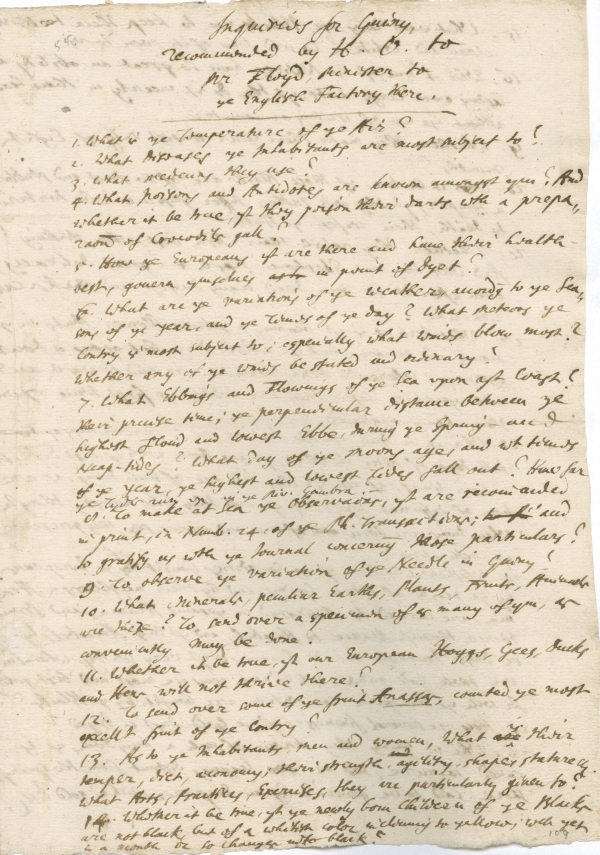

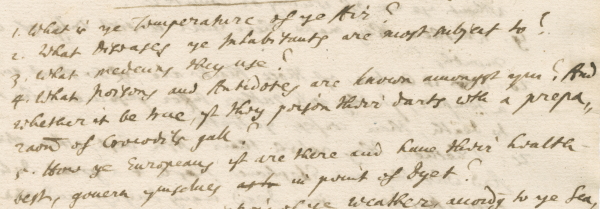

CLP/19/55 (detail)

Although it is unclear whether Mr Floyd made any successful discoveries, we have evidence that another minister stationed at Cape Coast Castle in the late seventeenth century, John Smyth, brought West African medical knowledge to the Society.

Smyth was hired in 1689 by the Royal African Company. He was one of the global correspondents of James Petiver FRS, and sent Petiver a collection of forty West African medicinal plants, including descriptions of how West Africans utilised the plants for a wide range of illnesses. This medical intelligence, communicated in a letter to physician Hans Sloane FRS and published in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, represents the first detailed account of West African materia medica and therapeutics in English:

Philosophical Transactions Volume 19 Issue 232

Philosophical Transactions Volume 19 Issue 232

Absent from the account, however, are the West African botanical and medical experts who instructed Smyth. They taught him about certain plants that were dried in the sun, powdered, and sniffed to cure headaches. They introduced Smyth to infusions made from boiling the unnena plant, which were applied to swollen limbs to dissipate fluid retention. Those who suffered with constipation drank decoctions from boiled plants mixed with palm wine. West Africans created ointments by pounding plant leaves and mixing them with palm oil to heal sores and wounds. Smyth learned that dysentery was treated with the pocumma plant, which was pounded, dried, baked and eaten. Treatments for stomach aches, smallpox, worms, venereal disease, toothaches, scurvy and haemorrhaging were among the lengthy list of cures Smyth learned from unnamed West African experts.

Petiver wrote that he was enclosing a description of African materia medica, and that great benefits would come to the European ‘Art or Mystery of Physick, if the Vertues of all Simples were more nicely inquired into, or better known’:

Philosophical Transactions Volume 19 Issue 232 (detail)

Philosophical Transactions Volume 19 Issue 232 (detail)

Much was at stake in such inquiries. In the early eighteenth century, according to Simon P Newman in A New World of labor: the development of plantation slavery in the British Atlantic (2013), life expectancy for Royal African Company employees stationed in West Africa was four to five years. Minimizing death, improving health and discovering new drugs for commercial gain were considered imperatives of empire.

Work begun by Mr Floyd, John Smyth, and the Royal Society would continue for more than a century. And news about West African medicine would continue to arrive in London: in 1722, James Phipps, chief merchant at Cape Coast Castle, wrote to his London employers: ‘We should be glad to have the assistance of an able Gardener, one that is well acquainted with Herbs, as we believe there may be many Simples found here, of very great benefit, being observed to be made use of by the Natives in Pharmacy, as well as Surgery and who succeed in many good Cures in both.’

The violent trafficking of millions of African people to the Americas has left our world with legacies we are reckoning with today. One such legacy is the lack of historical acknowledgement of West African people as scientists, botanical experts and medical practitioners, despite their presence in the archives. Today, African indigenous knowledge remains devalued. Writing in 2016, Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luyaluka noted: ‘African indigenous knowledge seems to many as unscientific, delusory and as no more than a bunch of magical beliefs.’ The history of medicine in the British slave trade challenges us to think otherwise.

Today, I am a professor working on my first book, To heal and to harm: medicine, knowledge, and power in the British slave trade. In the book, I develop the story of West African medical knowledge and its vital interest to British merchants, scientists and statesmen. The history of the British slave trade gives us the opportunity to acknowledge the rich intellectual worlds of West African people as essential to science, health and medicine.