Virginia Mills looks at the ornate decoration found in the Royal Society's Charter Book and other manuscripts in our collection.

In 2020 and 2021, the Royal Society – for obvious reasons – was unable to welcome new Fellows in person at the annual Admission Day ceremony. This summer will therefore see three ceremonies and nearly 200 Fellows formally admitted, including the yet-to-be-revealed 2022 cohort.

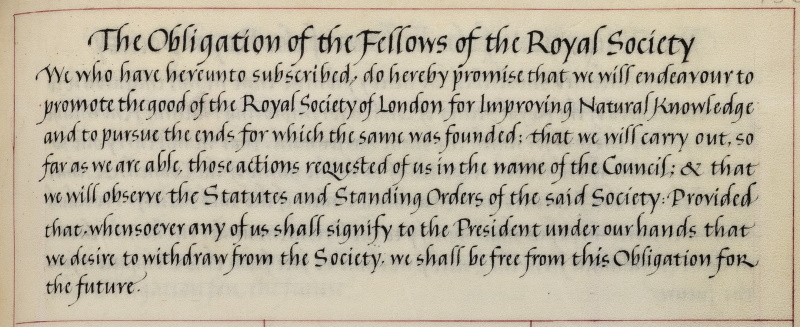

Those newly elected will be received by the President and given their Fellowship diploma. Then – most importantly from my record-keeping perspective – they’ll sign under the membership obligation in the Royal Society Charter Book, gifted to the Society by Founder Patron King Charles II in 1665.

Almost all Fellows have signed the Charter Book’s vellum pages. Their obligation, shown above, is a promise to work for the good of the Society and abide by its statutes, and has changed in wording, if not in spirit, over time. Every few years it needs to be repeated at the head of the blank pages ready for the next batch of Fellows. For this, we bring in our trusty calligrapher John R Nash.

Booking his next visit turned my attention to the calligraphy and illumination elsewhere in the Charter Book, together with another example from the archive which I’ve picked out here:

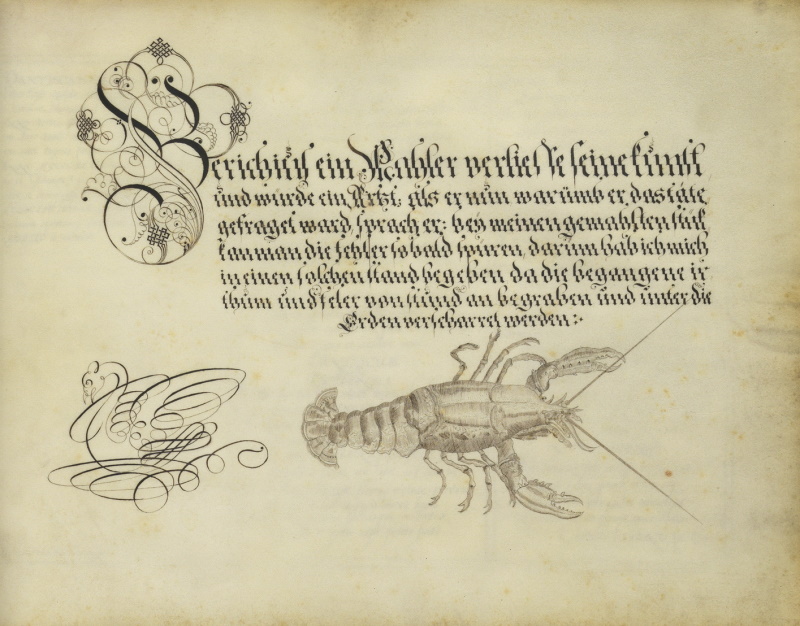

Though post-dating the Charter Book, a volume of scribal art, MS/68, represented by the above illustration, is one of the older examples in our collection. Gifted to the Society by Mr Owen, a visitor attending a meeting in 1701, it is recorded as being from ‘Dantzick’ (now Gdansk in Poland). It displays examples of a range of skills, from lettering in Roman, Gothic and Italic scripts to elaborately decorated borders, illuminations, and – surprisingly - detailed illustrations of freshwater animals. The full manuscript is available to view on Turning the Pages.

Our records don’t name the artist or suggest why such samples might have been of interest to the Royal Society. Perhaps it was a practical gift with the prospect of a commission for the artist, or simply a curiosity, given the antiquarian leanings of the Fellowship. The natural history illustrations would have been of interest: the Society published Willughby and Ray’s ‘History of fish’ in 1686, and recent research has shown that the sources for this work were varied, incorporating knowledge from artisans, fishermen and fishmongers as well as naturalists.

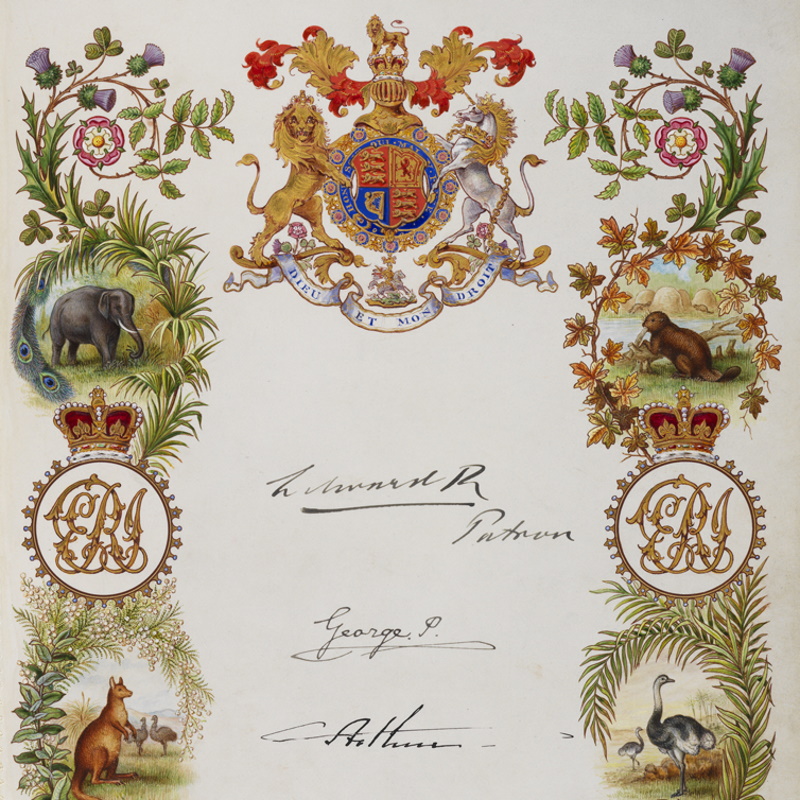

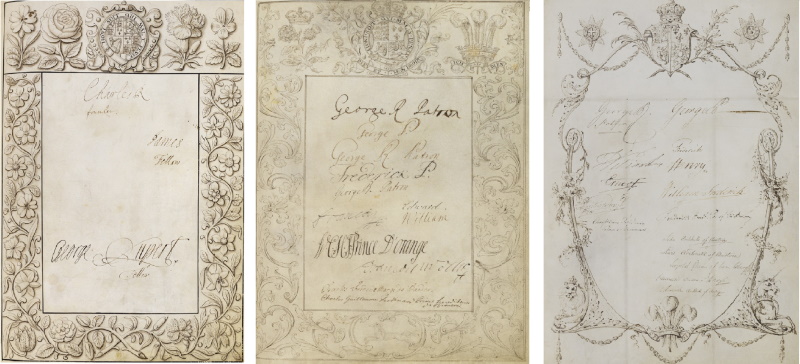

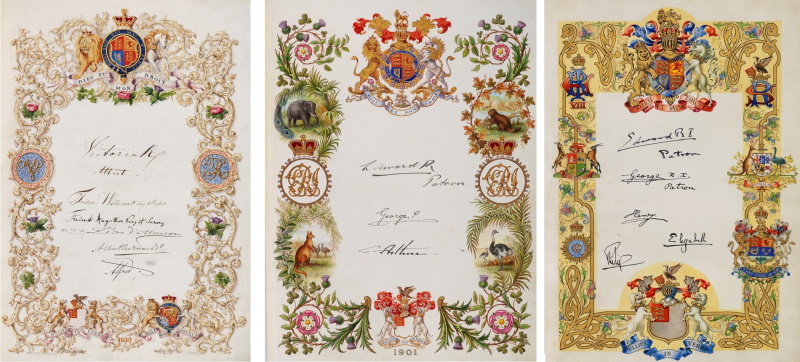

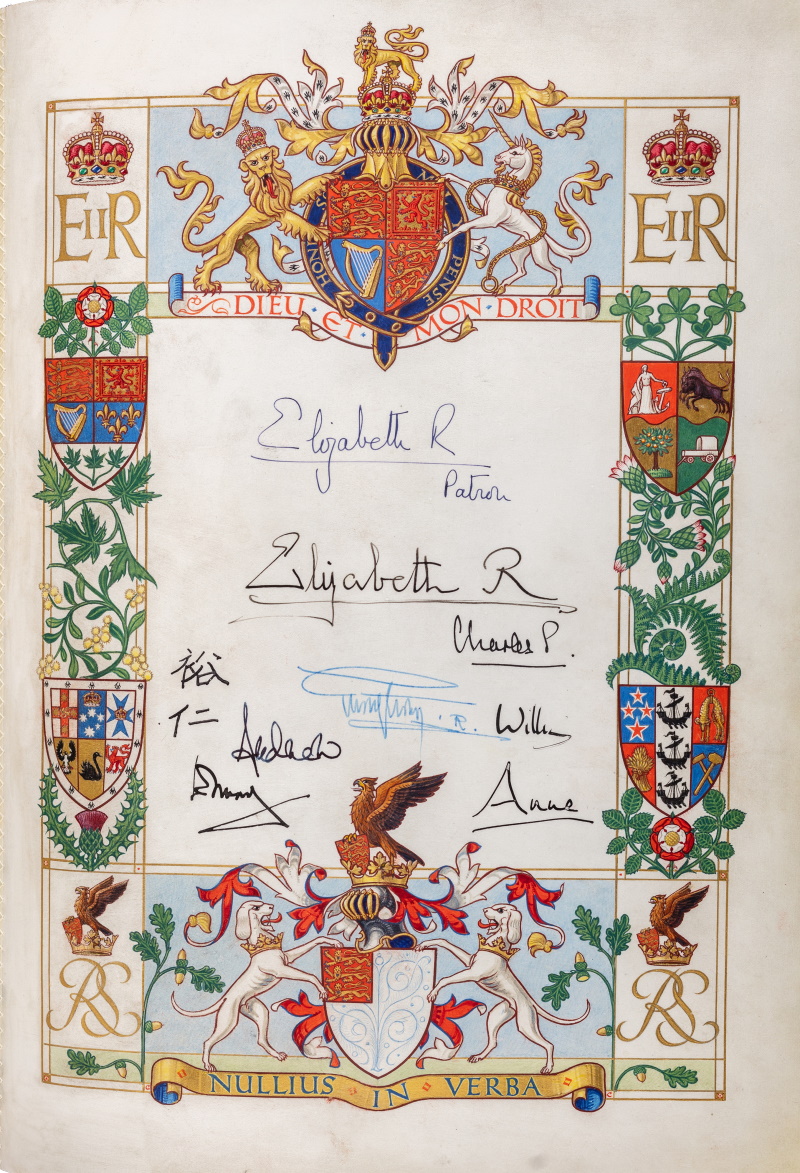

The sample book is archived as a record of the specific art form, but often the presence of calligraphy and illumination in the archive is more incidental. In the Charter Book it confers a sense of formality and occasion, nowhere more evident than on the so-called ‘Royal pages’. When each new monarch ascends to the British throne, they sign the Charter Book as Royal Patron on a bespoke and highly ornamented page. Since our Founder Patron Charles II, the book has received the signatures of twelve of the fourteen subsequent monarchs, with William and Mary, then Queen Anne, being the only exceptions. Regal signatures are spread across nine Royal pages, making the Charter Book a micro-study of changing styles and fashions in illumination over more than 350 years.

As you can see above, the first three Royal pages, representing monarchs up until 1820, are monochrome with recurring national and heraldic motifs. Colour appears in 1830 (below) with the patronage of William IV. The symbols gradually have a more martial feeling, perhaps, and the Society’s coat of arms appears alongside the Royal arms, in the style of the wider Gothic revival of the period.

William’s successor Victoria (1837) has a more Romantic style of decoration around her signature. The Edward VII page (1901) presents a straightforwardly colonial view of the British Empire, via a beaver, elephant, kangaroo and ostrich representing Britain’s Canadian, Indian, Australian and African dominions respectively. The style is much more naturalistic, with a diverse colour palette, but representing a complicated legacy. By the time of Edward VIII’s brief reign (1936), the imperial imagery is still in full force but with a return to more traditional heraldry with the arms of India, Canada, Australia and South Africa displayed:

With the exception of the 1830 Gothic revivalist page for William IV executed by the stained-glass artist Thomas Willement, the Royal page illustrations aren’t signed by the artists, unless better-trained eyes than mine can find any hidden signatures. We know that Willement left behind a portfolio and drawing board at the Royal Society when preparing his page, and was asked to send someone to collect them when they were still hanging around in 1832; however, a trawl through our records has revealed little else about the creation of the Royal pages.

Until we get to 1952 and the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, for which a new Royal page (below) was commissioned from Gerald Cobb, under the direction of the College of Arms. This, plus the persistence of heraldry, suggests that perhaps earlier work was done by the College of Arms too, as part of their (unsigned and anonymous) duties. I hope to root out more information so additional Royal pages can be attributed in future.

There are many other fine examples of calligraphy and illumination in our archive, including Fellows’ Nobel certificates with individually commissioned artwork, and congratulatory addresses sent to the Royal Society for our 250th anniversary celebrations. I’ll save these for my next illuminating post!