What's the earliest book in the Royal Society Library? Rupert Baker finds that the answer to this frequent question may not be quite so straightforward...

I’ve recently restarted our programme of behind-the-scenes Library tours for new staff at the Royal Society. Everyone who works here needs a close-up view of Newton’s death mask and Lord Rutherford’s potato masher, after all – it’s a rite of passage.

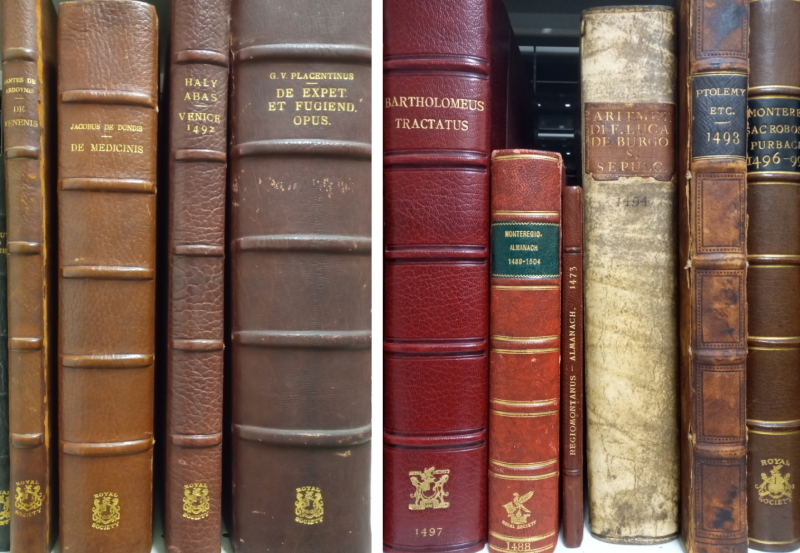

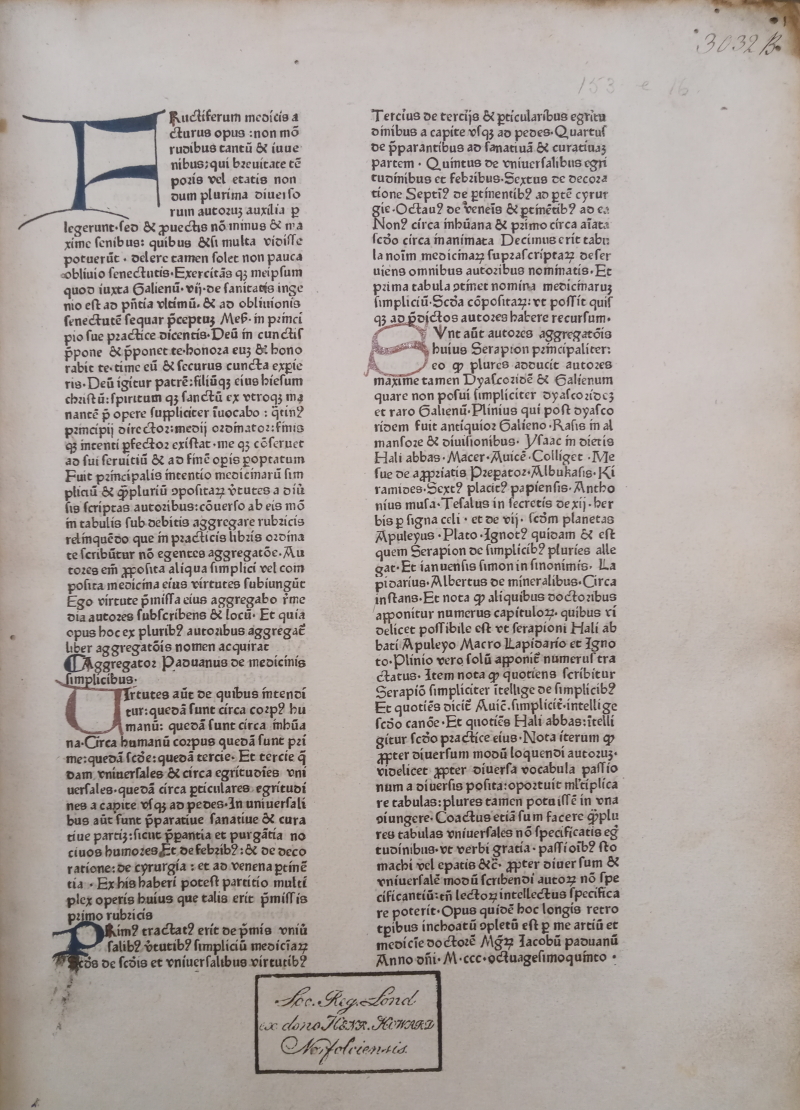

Because I’m the printed collections librarian, I tend to linger for a fair amount of the tour in our Rare Rooks Room, starting at the shelves labelled Incunabula: books printed before the year 1500. The FAQ at this point is usually ‘what’s your oldest book, then?’, and up to now I’ve answered this by pointing to the ‘large incunables’ section and the book in the left-hand image entitled De medicinis:

before reaching up to the ‘standard size’ shelf (right) and picking out the slim volume with the spine text ‘Regiomontanus – Almanach. 1473’, saying ‘this is our second-oldest book, but it’s much more interesting and has pictures, so let’s look at this one instead.’

Now the Regiomontanus does indeed have some very cool pictures, as my colleague Louisiane noted in her recent blogpost. And what’s more, with a publication date of 1474 (that spine annotation is a year out), it turns out that it’s probably our oldest book after all, as we’ve received new information which relegates De medicinis to second place.

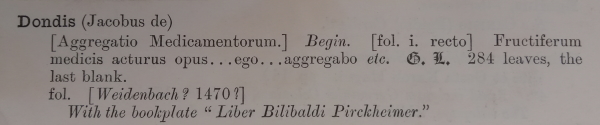

The De medicinis date adjustment stems from a recent revaluation of our printed collections for insurance purposes. Our online catalogue had a publication date of 1470 for De medicinis, citing F R Goff’s 1964 Incunabula in American libraries; the date, with a question mark, is also present on this small slip of paper attached to the book’s flyleaf:

However, our valuers were well versed in the identification of early printed books, and pointed us to the entry in the newer Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC) which suggests a publication date of ‘1475-80’. I’ve therefore amended our catalogue entry to ‘1475’ (with an explanation in the notes field), and double-checked the Regiomontanus ISTC entry, which does indeed say ‘1474’. Et voilà: we now have a new oldest book – with nice pictures! Hurrah!

Having done all this, I started to wonder whether I was being a bit mean to De medicinis, my background as a physics student possibly prejudicing me towards the history of astronomy over the history of medicine. I remembered looking at the book just long enough to ascertain that it didn’t have any woodcuts, volvelles or other ‘pretty pictures’, but on closer inspection – creeping guiltily back to the Incunabula shelves once my latest tour group had departed – it’s actually a volume with many noteworthy features.

For starters, its author, Jacopo Dondi (a.k.a. Jacobus de Dondis), turns out to have been an interesting character: a fourteenth-century clockmaker in Padua with sidelines in topological mapping, tides, astrology and – our main concern here – medicine. The manuscript of De medicinis dates back to 1355 and is preserved in the Vatican; ‘our’ printed volume is from the publishing house of the noted early German printer Adolf Rusch.

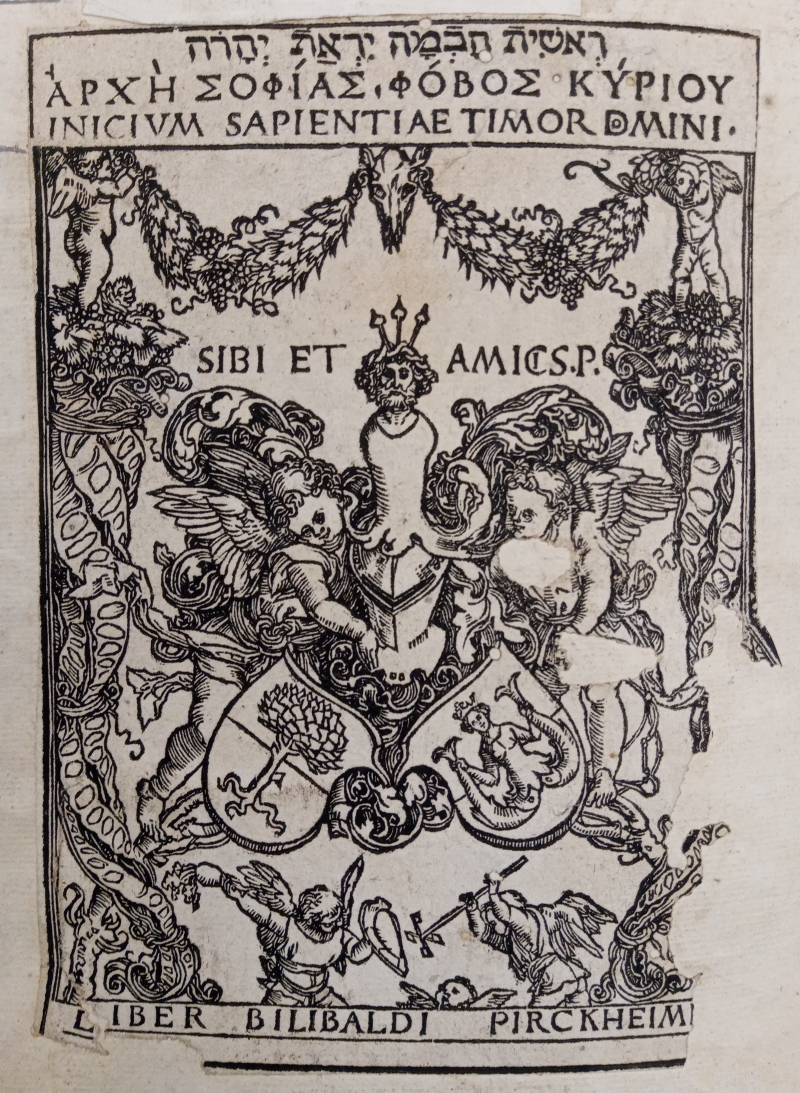

On opening the book, you’re immediately drawn to this Pirckheimer bookplate by Albrecht Dürer on the front pastedown – slightly more battered than the one featured in this blogpost on our Arundel Library collection, but still a rarity to cherish:

Then, on the opening leaf (there’s no formal title page, they’re a later development in the history of printing), you can see the Society’s ‘ex dono HENR. HOWARD Norfolciensis’ Arundel Library donation stamp, and – if you look carefully in the top right-hand corner – the Norfolk Library number, 3032B:

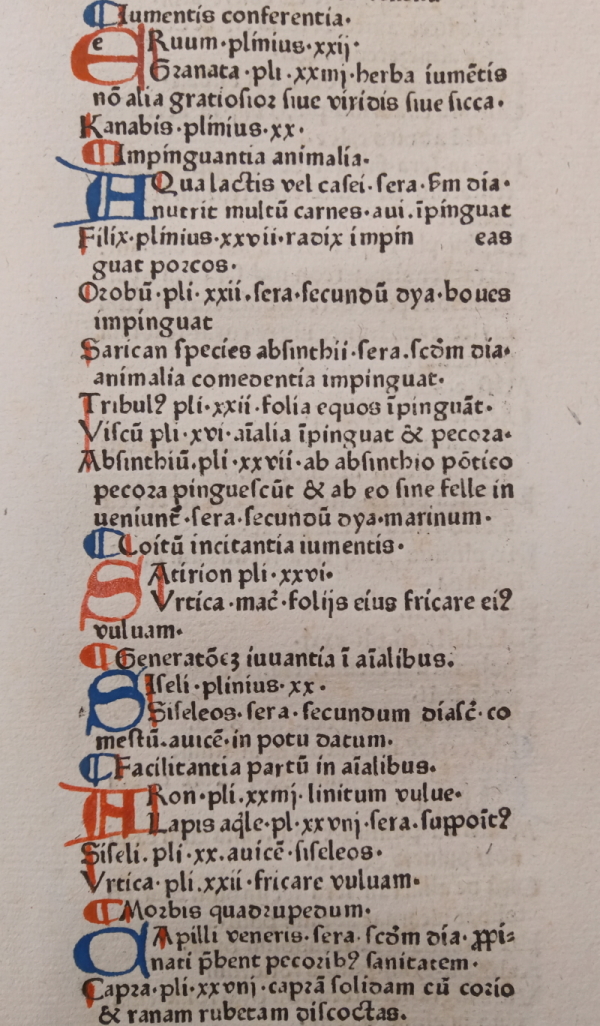

The text of De medicinis – illuminated throughout with hand-coloured red and blue capitals, still vivid after 550 years – consists of a series of remedies, treatises on topics such as surgery and pharmacology, and compendia of medical facts:

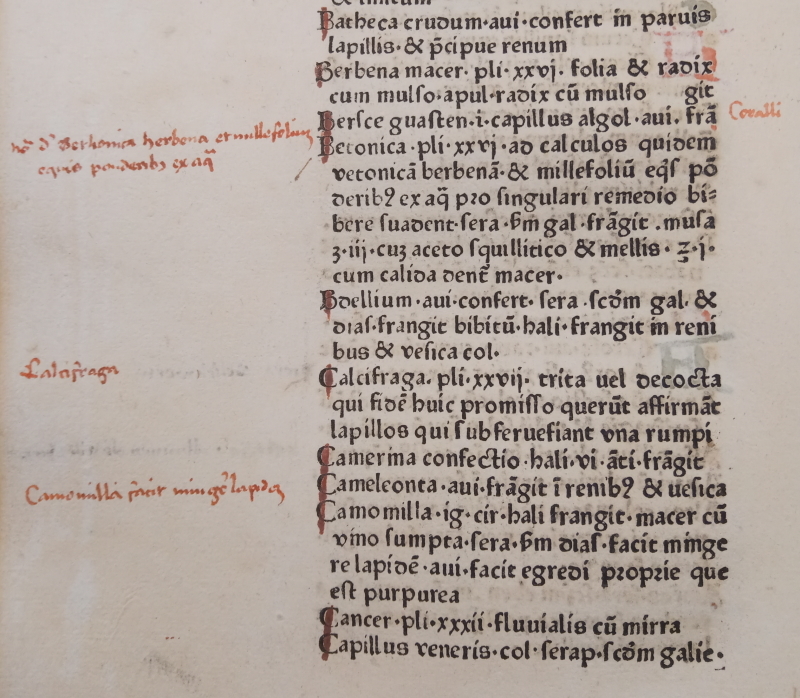

There are some annotations, in what looks like a contemporary hand, alongside this list of medicinal herbs such as betonica, calcifraga and camomilla – I’d love to get a historian of medieval medicine to look at these marginalia in detail, I’m sure there are some fascinating stories to be uncovered:

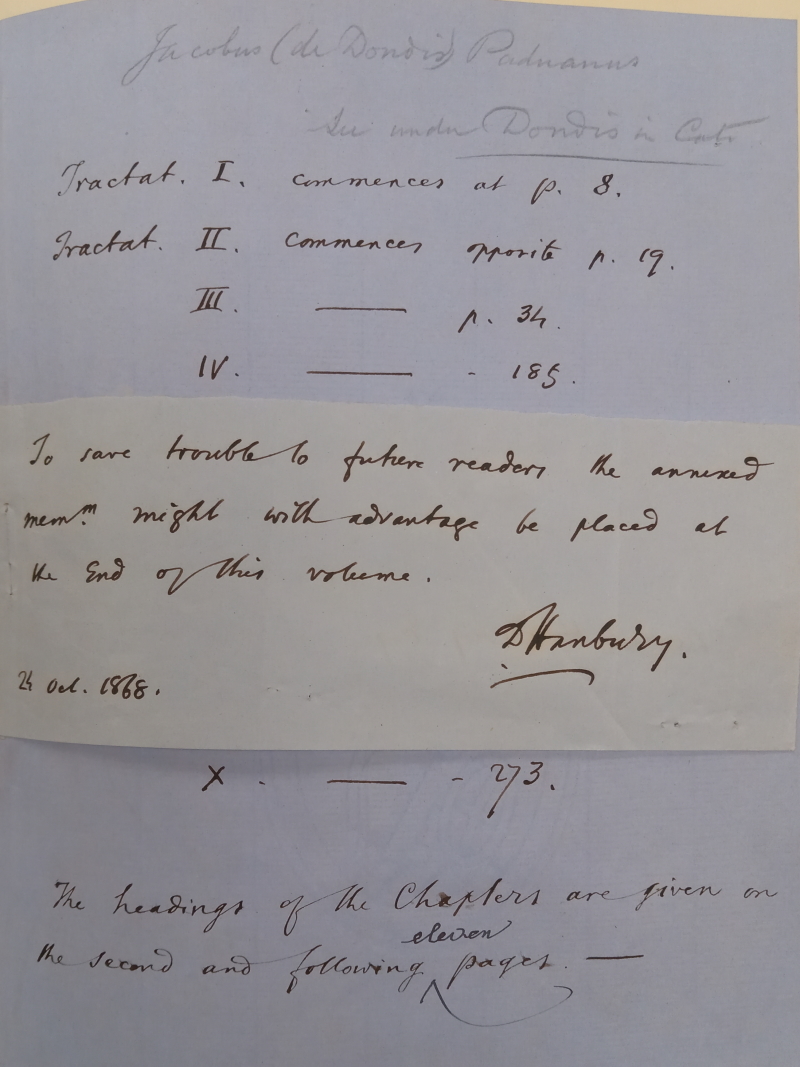

Then, right at the end, there’s evidence that one of our nineteenth-century Fellows took a scholarly interest in the book, and in helping future readers to navigate its pages. This tipped-in note, signed ‘D. Hanbury, 24 Oct. 1868’, lists the starting points for the various tracts within the text, ‘To save trouble to future readers’:

Its author, Daniel Hanbury FRS, had been elected to the Fellowship the previous year, ‘Eminent for his knowledge of Pharmaceutical Botany’, and it’s easy to imagine his joy at finding such a venerable text within the Society’s collections. I’ve certainly enjoyed getting to know our oldest – oops, second oldest – book a little better, and would love to show it off to interested readers, so do contact us if you’d like to book a Library research visit or one of our public tours. I might even throw in Rutherford’s masher, if you’re really lucky…