What became of the 'leg of the dodo' mentioned in the Royal Society's seventeenth-century museum catalogue? Jon Bushell investigates.

Last month, Kelly and Zach Weinersmith’s A City on Mars was announced as the winner of the 2024 Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize. All of the shortlisted titles are well worth a look, and The Last of its Kind by Gísli Pálsson caught my eye, with its sad tale of the loss of the great auk, hunted to extinction in the nineteenth century.

That got me thinking about another famous flightless bird, the dodo, which suffered a similar fate nearly two centuries earlier. Dodos, found on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, were a close relative of pigeons and doves. The first descriptions date to 1598, when the Dutch took possession of the previously uninhabited island.

Early accounts of dodo meat suggest that it was quite tough and not particularly appetising, and contrary to popular belief it was not hunting that drove the species to extinction. Instead, it was the introduction of animals including cats, dogs, livestock and rats that had a more profound impact, as did the deforestation carried out by the settlers themselves.

Study of the dodo (with a guinea pig for scale) by George Edwards, in volume 2 of his Gleanings of natural history (1760)

Study of the dodo (with a guinea pig for scale) by George Edwards, in volume 2 of his Gleanings of natural history (1760)

Modern scholarship generally dates the last confirmed sighting to 1662, when several Dutch sailors were marooned on Mauritius after their ship sank in a storm. One of the survivors, Volkert Evertsz, published an account of their time on the island after they were rescued, which included descriptions of wild dodos. Benjamin Harry, the first mate aboard the British ship Berkeley Castle, reported the crew eating dodo meat in Mauritius in 1681, but this was likely purchased from the Dutch settlers and may have come from another species of bird entirely.

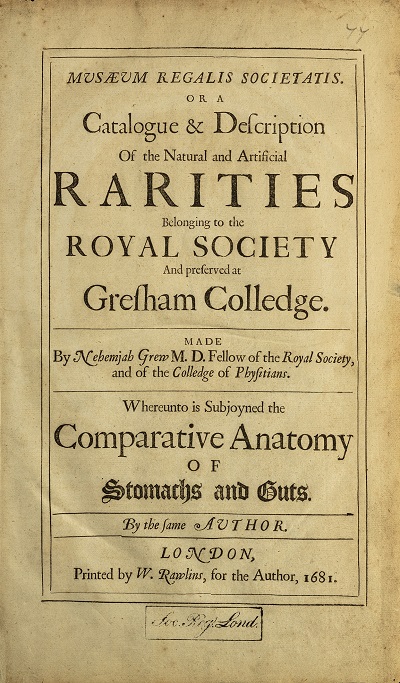

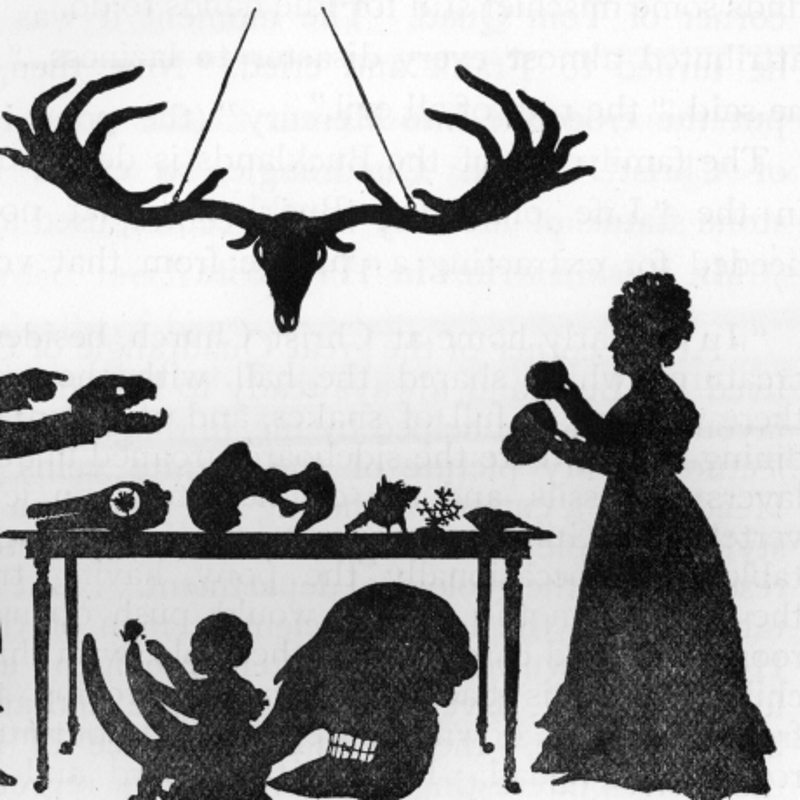

Dodo specimens were rare even before the species was driven to extinction, though the Society’s Repository collection did once contain the leg of a dodo, described in Nehemiah Grew’s Musaeum Regalis Societatis. The entry notes that the limb was ‘cover’d with a reddish yellow Scale’, indicating that the skin was also preserved. It isn’t entirely clear how this came into the Society’s possession: an account by Sir Hamon L'Estrange records a live dodo which was exhibited in London in 1638, and a preserved dodo leg was recorded among the specimens belonging to collector Robert Hubert in 1665. It’s quite possible that Hubert’s specimen was the remains of the 1638 dodo, which then ended up in the Society’s possession by 1681.

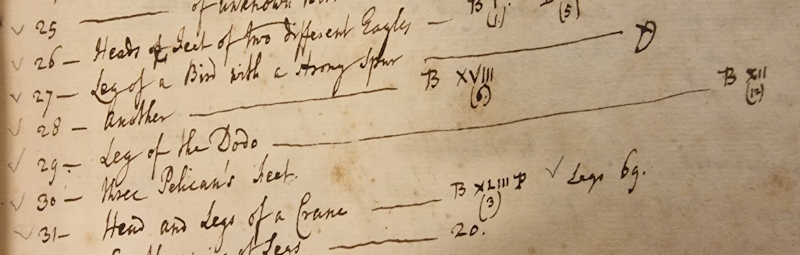

‘Leg of the Dodo’ recorded in a 1763 catalogue of the Society’s Repository (MS/417/1)

‘Leg of the Dodo’ recorded in a 1763 catalogue of the Society’s Repository (MS/417/1)

Whatever the case, the specimen was transferred to the British Museum along with many other artefacts when the Society moved from Crane Court to Somerset House in 1780. George Shaw included an account of it in his 1793 Naturalist’s Miscellany, along with a colour illustration. The image is accompanied by Shaw’s description of the dodo as ‘an animal so very rare, and of an appearance so uncouth, as to have given rise to some doubts as to its real existence’.

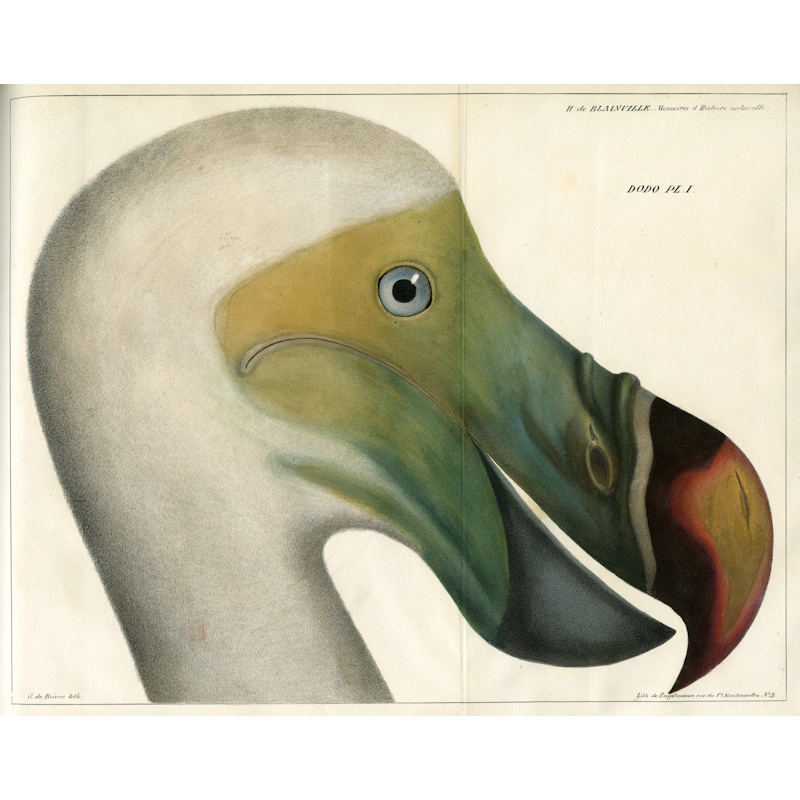

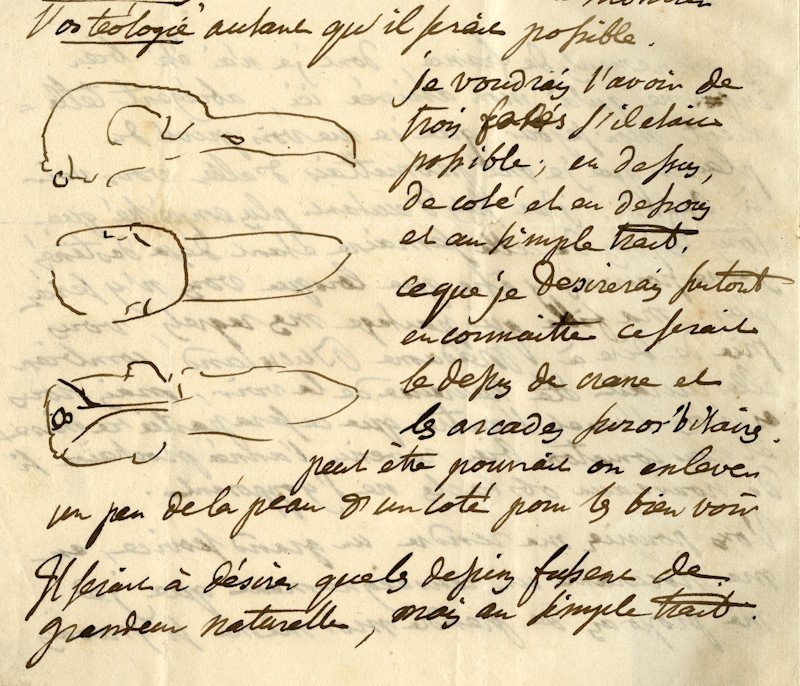

Describing the dodo as ‘rare’ at the end of the eighteenth century is definitely an understatement. But many did doubt the existence of the dodo entirely. The idea that an entire species could become extinct only began to be taken seriously in the nineteenth century, thanks in particular to the work of Georges Cuvier on mastodon fossils. Cuvier himself was also interested in the dodo, writing to William Buckland in 1830 asking for detailed drawings to be made of a head preserved in the Ashmolean museum in Oxford.

Cuvier’s letter to Buckland (MS/251/35)

Cuvier’s letter to Buckland (MS/251/35)

The Oxford dodo remains are not from the same bird as the Royal Society’s. It’s not clear how complete the Oxford specimen was when it was first presented to Elias Ashmole in 1659, but only the head and one leg remained by the 1820s, when John Edward Gray from the British Museum compared the London and Oxford remains. He noted a clear size difference between the two, which might indicate that Ashmole’s bird was a female while the Society’s was male. With the limited evidence available it’s hard to be sure, however.

One nineteenth-century treatise is The Dodo and its Kindred (1848) by Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alexander Gordon Melville. This set out to produce a detailed account of the dodo, as well as several other extinct birds from the same chain of islands as Mauritius, by studying the surviving remains. Strickland was a Fellow of the Royal Society and president of the Ashmolean, while Melville was an Irish anatomist who at this time was also working with Gideon Mantell studying the iguanodon.

The dodo, embossed on the Royal Society’s copy of The Dodo and its Kindred

The dodo, embossed on the Royal Society’s copy of The Dodo and its Kindred

Strickland and Melville recognised that the loss of the dodo was a direct consequence of human activity: ‘many species of animals and of plants are now undergoing this inevitable process of destruction before the ever-advancing tide of human population. We cannot see without regret the extinction of the last individual of any race of organic beings.’ Sadly, this wasn’t exactly followed by a clarion call for environmental activism; rather, they viewed human encroachment onto the natural world as simply inevitable, writing that ‘It is, therefore, the duty of the naturalist to preserve to the stores of Science the knowledge of these extinct or expiring organisms, when he is unable to preserve their lives’.

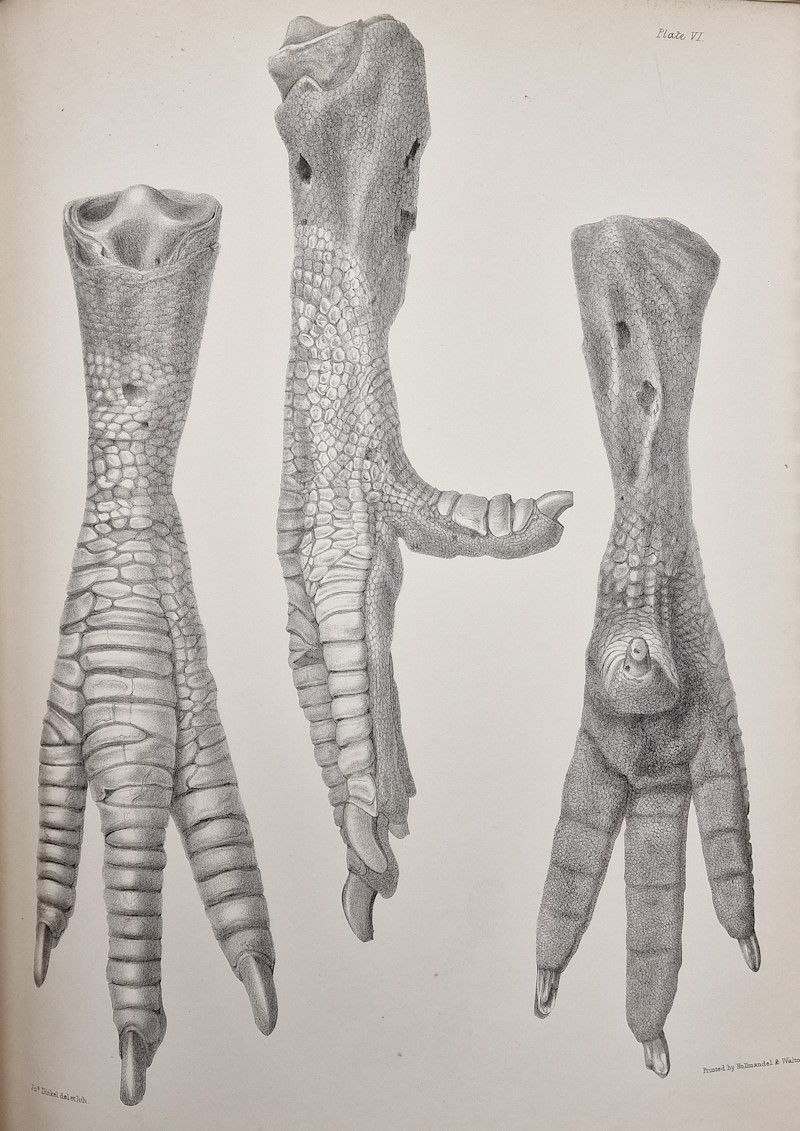

While Strickland and Melville’s attitude towards extinction might have been a little defeatist, their scholarship was thorough. With very few remains available, their study also took in historical written sources and artworks, including Roelant Savery’s famous painting of a dodo from the 1620s, which George Edwards donated to the British Museum in 1759. Strickland and Melville mentioned that the painting was on display at the museum in the Bird Gallery, along with the dodo’s foot, which was in a better state than one at the Ashmolean: ‘its excellent preservation exhibits the external characters of the tarsus and toes in a very interesting manner.’

Plate VI from The Dodo and its Kindred, depicting the London dodo specimen in the 1840s

Plate VI from The Dodo and its Kindred, depicting the London dodo specimen in the 1840s

We’re fortunate that the authors included a study of the London dodo leg in the book, because the specimen is now lost. Savery’s dodo painting remains at the Natural History Museum, but the leg has vanished from the collection. It was last mentioned in 1896 in the Dictionary of Birds by Alfred Newton and Hans Gadow, which noted that only the bones remained by this time; no trace of these has been found since. Skeletal dodo remains have been discovered in other collections, including a set of bones at the Grant Museum of Zoology in 2011. But as regards the specimen once held by the Royal Society, it seems to have gone the way of the dodo.

Header image from Mémoire sur le Dodo by H.D. De Blaineville, 1835 (RS.12997)